|

|

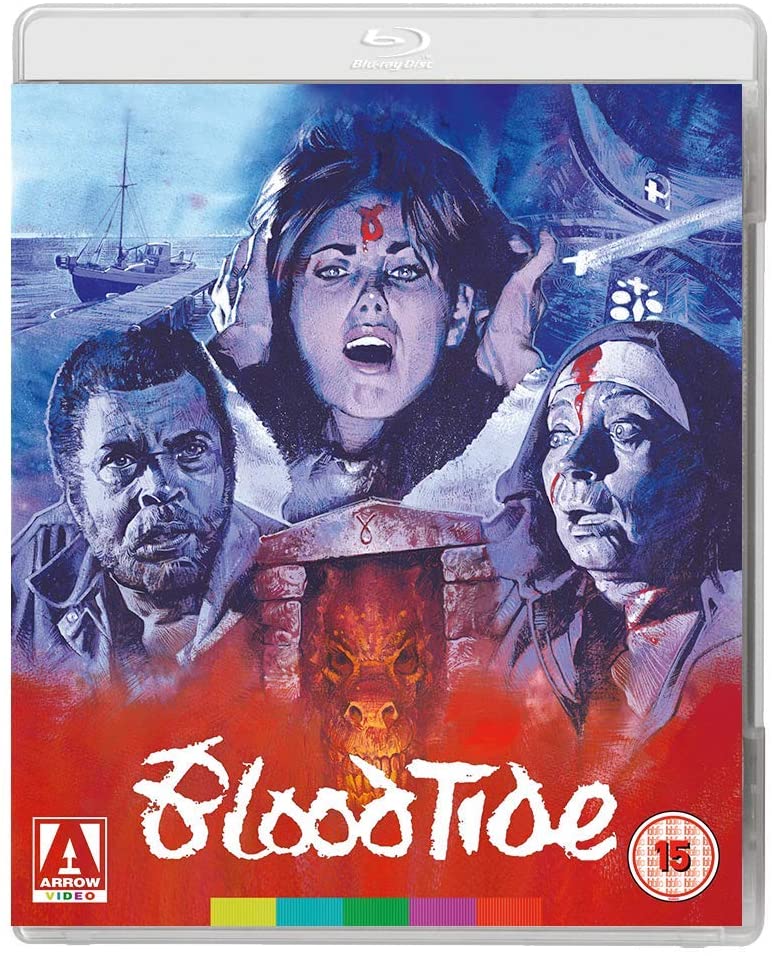

Blood Tide AKA Bloodtide (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (13th June 2020). |

|

The Film

Blood Tide (Richard Jefferies, 1982) Blood Tide (Richard Jefferies, 1982)

Synopsis: American Neil Grice (Martin Kove) and his wife Sherry (Mary Louise Weller) arrive on a Greek island, Synoron, looking for Neil’s missing sister Madeline (Deborah Shelton), an artist. On the island, they meet the mayor, Nereus (Jose Ferrer), who makes it clear that Neil and Sherry are not welcome. Neil spots Madeline and the couple follow her to the home of Frye (James Earl Jones), a diver and treasure hunter, where they also meet Frye’s friend (lover?) Barbara (Lydia Cornell). Frye has discovered an underwater cave containing ancient coins. He is unaware that centuries ago, these coins were placed on rafts with victims of sacrifice; these rafts were pushed into the cave where the victims would be devoured by an immortal creature of unknown origin. Searching for more coins, Frye uses underwater explosives to demolish part of the cave wall, unaware that he is freeing the monster that has been sealed behind it. Subsequently, a series of mysterious deaths and disappearances take place. Neil and Sherry are prevented from leaving the island. When Barbara is attacked and killed by the monster whilst swimming, Frye and the others are spurred into action. Frye becomes determined to track down and destroy the creature. Meanwhile, Madeline’s status as a virgin makes her a prime candidate for ritual sacrifice.  Critique: Filmed in 1980 but unreleased until 1982 in the US and later in other territories, Blood Tide is a curious mish-mash of ideas and fragments predominantly borrowed from other pictures. The script, by director Richard Jefferies and Greek polymath Nico Mastorakis (whose films Island of Death, Hired to Kill, The Zero Boys and The Wind we have reviewed here, here, here, and here, respectively), Blood Tide pays homage to films as diverse as Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) and Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1972), by way of some nods to Lovecraft’s work. The film was shot in Greece: the location is the medieval castle town of Monemvasia, where Mastorakis’ 1986 picture The Wind was also lensed. Critique: Filmed in 1980 but unreleased until 1982 in the US and later in other territories, Blood Tide is a curious mish-mash of ideas and fragments predominantly borrowed from other pictures. The script, by director Richard Jefferies and Greek polymath Nico Mastorakis (whose films Island of Death, Hired to Kill, The Zero Boys and The Wind we have reviewed here, here, here, and here, respectively), Blood Tide pays homage to films as diverse as Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) and Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1972), by way of some nods to Lovecraft’s work. The film was shot in Greece: the location is the medieval castle town of Monemvasia, where Mastorakis’ 1986 picture The Wind was also lensed.

Blood Tide begins with an ominous voice over. Opening with a voice over is generally fairly unremarkable, but what’s notable about Blood Tide’s opening narration is that it is in the third person – usually reserved for either historical epics or stories with a strong mythical dimension. ‘Before the dawn of civilisation, in the early light of man’s existence, life was an eternal struggle between evil and good’, the narrator declares, ‘The ancients knew the way to placate the beast that lurked beneath the eternal sea and within the consciousness of man. Sacrifice. Virgin sacrifice [….] Deep in the heart of man, the primeval urge to give new life to an ancient ritual lingers on’. As the voiceover continues, we see onscreen a girl being prepared for sacrifice by her community: the ritual of a mark being made on her forehead, and placed on a raft which is pushed into a cave where… something lurks in the water. Blood Tide begins with an ominous voice over. Opening with a voice over is generally fairly unremarkable, but what’s notable about Blood Tide’s opening narration is that it is in the third person – usually reserved for either historical epics or stories with a strong mythical dimension. ‘Before the dawn of civilisation, in the early light of man’s existence, life was an eternal struggle between evil and good’, the narrator declares, ‘The ancients knew the way to placate the beast that lurked beneath the eternal sea and within the consciousness of man. Sacrifice. Virgin sacrifice [….] Deep in the heart of man, the primeval urge to give new life to an ancient ritual lingers on’. As the voiceover continues, we see onscreen a girl being prepared for sacrifice by her community: the ritual of a mark being made on her forehead, and placed on a raft which is pushed into a cave where… something lurks in the water.

When, in the present day, Neil and Sherry moor their boat on the island, they explore the labyrinthine medieval streets of the town. The streets are initially eerily deserted, but giggling children soon arrive on the scene and throw a cat at the couple, suggesting child-enacted cruelty to come. This doesn’t happen, of course, but the total, deliberately enigmatic, effect of this sequence is not dissimilar to the early scenes in Narcisco Ibanez Serrador’s 1976 film ¿Quién puede matar a un niño? (Who Can Kill a Child), in which a British couple (Lewis Flander and Prunella Ransome) arrive on an island populated solely by murderous children. Blood Tide immediately establishes a sense of mystery and threat within this location: where are all the adults? What has happened to the population?  This is soon disrupted, however, by the arrival of the town’s mayor, Nereus (Jose Ferrer). Nereus makes Neil and Sherry feel unwelcome and clearly indicates he would rather they leave the island. However, the couple refuse, and Jefferies makes similar use of the winding medieval streets and alleyways of Monemvasia to Mastorakis’ use of the same location in The Wind: not long after their first encounter with Nereus, Neil spots – or thinks he spots – his sister Madeline, and they follow her fleeting figure to a building where they see her in a meeting with Frye, who is introduced quoting Shakespeare – something he does throughout the film. This leads Neil to refer to Frye, on their first meeting, as ‘some latter-day Paul Robeson spewing Shakespeare’. Neil and Sherry soon show themselves to be less than enlightened when Neil mockingly asserts that Frye and Madeline ‘stick out here like Man Friday and Mrs Crusoe’, and Sherry assumes that Madeline is ‘into some good drugs, and Frye is giving her a decent price’. This is soon disrupted, however, by the arrival of the town’s mayor, Nereus (Jose Ferrer). Nereus makes Neil and Sherry feel unwelcome and clearly indicates he would rather they leave the island. However, the couple refuse, and Jefferies makes similar use of the winding medieval streets and alleyways of Monemvasia to Mastorakis’ use of the same location in The Wind: not long after their first encounter with Nereus, Neil spots – or thinks he spots – his sister Madeline, and they follow her fleeting figure to a building where they see her in a meeting with Frye, who is introduced quoting Shakespeare – something he does throughout the film. This leads Neil to refer to Frye, on their first meeting, as ‘some latter-day Paul Robeson spewing Shakespeare’. Neil and Sherry soon show themselves to be less than enlightened when Neil mockingly asserts that Frye and Madeline ‘stick out here like Man Friday and Mrs Crusoe’, and Sherry assumes that Madeline is ‘into some good drugs, and Frye is giving her a decent price’.

Jones’ presence anchors the film. Though he is not the protagonist – in fact, in accidentally loosening the monster, he could arguably be labelled as its antagonist – he brings a gravitas to his performance as Frye. The heavy-drinking, combined with the haunted air Jones projects, suggests a man possessed by something in his past – beyond the simple weirdness of the film’s setting. When Frye dives into the cave and uses explosives to shatter the ad-hoc ‘doorway’ to the creature’s lair, having seen the virginal sacrifice in the film’s opening sequence we might wonder if he is deliberately freeing the creature; but he seems to be a simple treasure hunter, motivated by greed, who is looking for the coins that were placed in the vessels with the ancients’ sacrificial victims. When the cave wall crumbles, a strange roaring is heard, and mist pours out of the hollow and fills the cave. It’s all very ominous, but fundamentally the film’s structure is recognisable from numerous ‘creature features’ of the 1950s and 1960s, the kind that Larry Cohen deadpan-parodied in the superb Q: The Winged Serpent (1982), a contemporary of Blood Tide – a mysterious, ancient creature is disturbed and liberated by greed and self-interest (Frye’s search for the coins), unleashing an ancient evil upon the world which must be driven back or destroyed.  The film’s most blatant homage/pastiche is to Spielberg’s Jaws. Barbara is shown sunbathing topless. She spots a group of local men watching her: ‘I thought you Greeks only liked little boys’, she shouts at them angrily before going swimming. Point-of-view shots from beneath the surface are accompanied by strange (and, admittedly, slightly comical) gurgling sounds; there’s a clear attempt to draw on the striking imagery from the opening sequence of Jaws, but without a corollary to John Williams’ iconic score for that film, the sequence falls flat. The creature, however, grabs Barbara and pulls her beneath the water in a surge of blood. The film’s most blatant homage/pastiche is to Spielberg’s Jaws. Barbara is shown sunbathing topless. She spots a group of local men watching her: ‘I thought you Greeks only liked little boys’, she shouts at them angrily before going swimming. Point-of-view shots from beneath the surface are accompanied by strange (and, admittedly, slightly comical) gurgling sounds; there’s a clear attempt to draw on the striking imagery from the opening sequence of Jaws, but without a corollary to John Williams’ iconic score for that film, the sequence falls flat. The creature, however, grabs Barbara and pulls her beneath the water in a surge of blood.

For much of the film’s running time, Madeline exists on the periphery of the story, and until the mid-way point her role in the narrative is fairly ambiguous. An artist, Madeline has at the start of the film been missing for four months. She was drawn to the island mysteriously: ‘She had a strange interest in this island’, Neil notes, ‘Some particular curiosity’. The virginal Madeline is a brunette, and juxtaposed visually with Barbara and Sherry (both blonde). As the nature of the island’s connection to the creature in the cave is revealed, Madeline’s behaviour becomes more mysterious. She has been repairing a religious icon in the possession of a group of nuns on the island, and during the restoration she discovers, beneath the surface of the upper layer of paint, another painting beneath it which depicts a cruciform man and a serpent. ‘I think I like the other one more’, Sister Anna (Lila Kedrova) observes, ‘Good triumphs over evil. This one, it is almost as if evil were about to triumph over good’. However, beneath this painting is another, much older, Pagan artwork on wood which, Madeline asserts, predates the birth of Christ. ‘This icon is work unto Jesus Christ’, Sister Anna exclaims, horrified, ‘It could not possibly be older than him’. This older artwork depicts a creature with a huge, erect phallus, in front of which a woman is kneeling. There’s a clear, post-Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979) codification of the film’s monster as presenting a sexual threat to the women who are its victims – something made even more obvious in a spate of 1980s SF/fantasy films, including the likes of Norman J Warren’s Inseminoid (1981). When the creature runs amok and kills (rapes to death?) a group of nuns, it’s difficult not to think of Ken Russell and wonder what he might have done with similar material.  What is somewhat interesting in Blood Tide is the manner in which the rituals of the past continue into the present – despite the fact that the creature has been ‘imprisoned’ for centuries. As noted above, Neil and Sherry are met upon their arrival on the island with the strange behaviour of the local children, whose act of throwing a cat at the couple seems like an index of violence to come. They (Neil and Sherry) are subsequently introduced to the mayor Nereus, who regards them with suspicion and tries to hasten their departure, in a seemingly clear indication that the community on the island has something to hide. (‘These Greeks aren’t known for their rationality’, Frye tells Neil and Sherry dryly.) After Barbara is killed by the creature, a funeral is held for her, and Nereus stops the procession so that he can place a coin in her mouth: ‘Hail, God of Water’, he declares quietly. In response, Frye angrily tells him, ‘You do your voodoo on your own people!’ Shortly afterwards, Frye witnesses a group of children performing a ritual – apparently sacrificing a girl – in a sequence that recalls the young people’s arcane rituals conducted in the derelict church at Bix Bottom in Piers Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971). What is somewhat interesting in Blood Tide is the manner in which the rituals of the past continue into the present – despite the fact that the creature has been ‘imprisoned’ for centuries. As noted above, Neil and Sherry are met upon their arrival on the island with the strange behaviour of the local children, whose act of throwing a cat at the couple seems like an index of violence to come. They (Neil and Sherry) are subsequently introduced to the mayor Nereus, who regards them with suspicion and tries to hasten their departure, in a seemingly clear indication that the community on the island has something to hide. (‘These Greeks aren’t known for their rationality’, Frye tells Neil and Sherry dryly.) After Barbara is killed by the creature, a funeral is held for her, and Nereus stops the procession so that he can place a coin in her mouth: ‘Hail, God of Water’, he declares quietly. In response, Frye angrily tells him, ‘You do your voodoo on your own people!’ Shortly afterwards, Frye witnesses a group of children performing a ritual – apparently sacrificing a girl – in a sequence that recalls the young people’s arcane rituals conducted in the derelict church at Bix Bottom in Piers Haggard’s Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971).

In a later sequence, the Americans witness a strange ritual conducted on a terrace at night, the locals re-enacting the ritual sacrifice shown in the film’s opening sequence; the scene amplifies, until the Americans attempt to stop the sacrifice of a young girl that seems about to take place, and it is revealed that the ritual is simply an act of carnival performance. ‘Please do not interfere with our local customs’, Nerese tells them, ‘At best it would be ill-mannered. At worst, it would be sacrilege. You came here as tourists. We off you a little local colour – a young girl going to communion’. When Frye angrily asks Nereus, ‘What new evil are you trying to conjure up now?’, Nereus responds: ‘Mr Frye, there is no such thing as “new” evil. Evil is old and has always been with us And as for conjuring it up, the small ritual which you are witnessing had its origins thousands of years ago and was designed to ward off, to placate, evil’. Viewers might be reminded, quite strongly, of the community on the island of Summerisle (in Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man, 1972), with their closed rituals which deliberately mock the film’s outlander protagonist played, or perhaps of similar closed communities in, for example, H P Lovecraft’s ‘The Dunwich Horror’ (1928) – with the seemingly immortal creature that has been sealed in the underwater cave having quite clear parallels with the monsters of Lovecraft’s work.

Video

Running for 87:18 minutes and apparently uncut, Blood Tide is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec and fills approximately 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The presentation uses the film’s original theatrical ratio of 1.85:1. Running for 87:18 minutes and apparently uncut, Blood Tide is presented in 1080p using the AVC codec and fills approximately 25Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The presentation uses the film’s original theatrical ratio of 1.85:1.

The film, shot on 35mm colour stock, is presented excellently on Arrow’s Blu-ray. The presentation is based on a new restoration from a 4k scan of the negative. There is a very rich level of fine detail, and the encode to disc ensures that the presentation retains a very film-like grain structure, including in shots which feature lots of particle effects (for example, when the mist appears in the cave after Frye dynamites the cave wall and frees the creature). There are some shots (mostly of Deborah Shelton) which feature deliberate soft focus photography, and these are carried well in this presentation. Whilst much of the film is shot under the harsh Mediterranean sun which results in high contrast even in daylight scenes, low light scenes appear to have been shot on slightly faster, grainier film stock. Contrast levels in this presentation are consistently pleasing, midtones having a sense of depth and richness, tapering off into the toe where deepest blacks reside. Colours are deep and consistent, for the most part naturalistic – though there are some expressionistic splashes of colour in some of the night-time scenes, notably a shot of Madeline’s head appearing just above the surface of the water which appears to pay homage to the climax of Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979). The shoulder is balanced and even. In sum, it’s an excellent, filmlike presentation. NB. There are some full-sized screengrabs at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is deep and rich, dialogue being audible throughout. It is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. These are easy to read and accurate.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with director Richard Jefferies. In a track moderated by Michael Felsher, Jefferies talks about his involvement in Blood Tide. He discusses how he became interested in filmmaking via a youthful fascination with magic. Jefferies reflects at length on his approach to filmmaking and his intentions with the film, admitting that the production faced some limitations in terms of budget, etc. He discusses shooting on location and working with an international crew, and he talks about the casting of the picture and the performances. - ‘Swept by the Tide’ (28:58). The ever-effervescent Nico Mastorakis talks about his career, jokingly calling himself ‘a horror of a director’. He discusses issues with being pigeonholed as a filmmaker and reflects on his varied body of work. Mastorakis talks about the approach to writing Blood Tide. He suggests that he and Jefferies tried to distinguish the film from ‘the typical monster movie’ by the casting. Mastorakis reflects on the issues faced in financing the film, including some less than above-board practices by the film’s original financiers. He also discusses at length the casting of the film. - The film’s trailer (2:19). - A new 2020 trailer (1:50).

Overall

Blood Tide builds up to its ‘big’ reveal of the immortal creature which, when it finally appears on screen, is little more than an unconvincing, vaguely dinosaur-like rubber monster. In some ways, the film would perhaps have been more effective if the creature had never been shown – especially after the horrifying image that Madeline discovers beneath the religious icon she is restoring. Where Larry Cohen’s Q: The Winged Serpent looks back to the paradigms of 1950s monster movies and reworks these with irony, Blood Tide is much more po-faced in its approach. There are numerous nods, both on a narrative level and visually, to other films. James Earl Jones’ performance as Frye gives the film a sense of much-needed playfulness, and the setting is evocative and atypical. Blood Tide builds up to its ‘big’ reveal of the immortal creature which, when it finally appears on screen, is little more than an unconvincing, vaguely dinosaur-like rubber monster. In some ways, the film would perhaps have been more effective if the creature had never been shown – especially after the horrifying image that Madeline discovers beneath the religious icon she is restoring. Where Larry Cohen’s Q: The Winged Serpent looks back to the paradigms of 1950s monster movies and reworks these with irony, Blood Tide is much more po-faced in its approach. There are numerous nods, both on a narrative level and visually, to other films. James Earl Jones’ performance as Frye gives the film a sense of much-needed playfulness, and the setting is evocative and atypical.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release contains an excellent presentation of the film, based on a restoration taken from the film’s negative. The contextual material is equally good, particularly the interview with the always-engaging Mastorakis. Please click the screengrabs below to enlarge them.

|

|||||

|