|

|

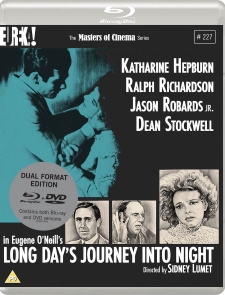

Long Day's Journey Into Night

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Eureka Review written by and copyright: Eric Cotenas (22nd March 2020). |

|

The Film

Oscar (Best Actress in a Leading Role): Katharine Hepburn (nominated) - Academy Awards, 1963 Golden Globe (Best Actress - Drama): Katharine Hepburn (nominated) - Golden Globes, 1963 Palme d'Or: Sidney Lumet (nominated), Best Actor: Dean Stockwell, Jason Robards, and Ralph Richardson (won), Best Actress: Katharine Hepburn (won) - Cannes Film Festival, 1962 The Tyrone family – faded stage actor James (The Wrong Box's Ralph Richardson), fragile wife Mary (The Philadelphia Story's Katherine Hepburn), and their sons: drunken wastrel son Jamie (Something Wicked This Way Comes's Jason Robards Jr.) and sensitive Edmund (The Dunwich Horror's Dean Stockwell) – are not of the "Summer People." James and Mary occupy their summer house all year round, with James making land deals that have made him cash poor and Mary having recently returned from a sanitarium stay after her latest bout with morphine addiction. Jamie, in a more mediocre stage career, takes to the stage during the season and drinks his pay away, returning home to work on the property every summer. World-traveler Edmund has returned from South America with a cough to be babied by his mother. James and Jamie, however, suspect that Edmund has consumption and are waiting for the doctor's test results, as worried as Edmund about that Mary may backslide since her cherished father died from consumption. James and Jamie cannot hide their bitter disappointments in each other from each other or Mary and Edmund; but it seems to serve as a distraction from Jamie's and Edmund's separate nagging suspicions that Mary's wandering about the house at night is a sign that she is using morphine again, especially since Edmund is unaware that his mother is not just a one-time user but a "dope fiend." Fearing for his mortality, Edmund wants his mother to be prepared. As day passes into night and both Mary and Jamie give into their addictions, James' own righteous self-image that has withstood their accusations of miserliness, coldness, drunkenness, and possible womanizing, takes a beating from Edmund when his own mortality seems less important to his father than teaching his children "the value of a dollar." Unproduced at the time of its completion in 1941-1942 by orders of writer Eugene O'Neill to publisher Harper not to publish the play and other until twenty-five years after his death (1978), Long Day's Journey into Night was published in 1956 by order of O'Neill's widow (whereupon O'Neill received a posthumous Pulitzer Prize the following year) and had its premiere in Sweden in 1962 where it must have been a major influence on Ingmar Bergman and his chamber films/plays, particularly Through a Glass Darkly since he would direct a stage production of it in 1988 to celebrate both the centenary of O'Neill's birth and the bicentennial of Sweden's Royal Dramatic Theatre. With the acknowledgement that the play is heavily autobiographical, O'Neill's quintessential "dark night of the soul" exploration – in which a stillborn child is also named Eugene – is a masterpiece of verbal exchange in which "sorry" is uttered so many times that it becomes apparent that it has lost its meaning no matter how much each character seems to think they do regret their uttered sharp or nasty remarks. "Sorry," and "that was nasty, I didn't mean it," have more of a rhythmic function in the dialogue as if things can no longer be repressed even if it appears they have been said many times before and hit their mark since it is the characters' self-image that is threatened as the memories in which they seek comfort can no longer be sustained. The film was produced by Ely Landau, a veteran of radio plays and live TV plays whose subsequent subscription-funded American Film Theatre four-walled theaters across the country to show a series of faithful and uncompressed for time screen adaptations of theatrical properties (including O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh), and this Sidney Lumet-directed adaptation – following screen adaptations of A View from the Bridge and 12 Angry Men after a decade of TV plays for the likes of Play of the Week (for which Lumet had earlier helmed an adaptation of The Iceman Cometh), Playhouse 90, and Kraft Television Theatre), the O'Neill adaptation feels like a dry run for that later undertaking with its uncompromising length, Lumet's attempts to open up the film visually not only with a handful of exteriors but also camerawork that tries to downplay a certain staginess that sets in during some of the more intense scenes in which a camera move or cut might break the spell, and the attribution of the screenplay to the late O'Neill placing the primacy of the original text over the cinematic adjustments (Hepburn would later star in his production of Edward Albee's A Delicate Balance as a James-like character who tasks herself with maintaining equilibrium even at the cost of being seen as cold and uncaring to her fraught family and friends). For the most part, Lumet does achieve a visual style that does equate to the emotions of the characters so much as frame their emotional isolation from within rather than observe the rooms of the house as a stage, pulling back from Hepburn's Mary as she curls up on the floor, pushing in tight on Richardson's James or Robard's Jamie as they can no longer keep their composure, or observing Stockwell's Edmund with a certain fondness shared by the other three until he lunges forward into sharp focus. The play has been revived several times for the stage as well as television productions including a 1987 version starring Jack Lemmon, an African-American version starring Thommie Blackwell, and a live version by BroadwayHD.

Video

Released theatrically by Embassy Pictures, Long Day's Journey Into Night went into TV syndication through American International in a version running roughly a half-hour shorter with a number of deletions from the final third of the film. The film subsequently ended up with Republic Pictures who released the film on videotape in the eighties and a thirtieth anniversary laserdisc in 1992, the fullscreen master of which appeared on Republic's DVD in 2004. An HD master was struck when the Republic titles went to Paramount through Aaron Spelling's selling of the Taft library, and it made its Blu-ray debut in 2012 on Olive Films' barebones Blu-ray. The same master has been used by Eureka for their 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 1.85:1 widescreen Blu-ray, and its age is really only terribly apparent in the windowboxed 1.66:1 credits and some faintly grayish blacks that spoil a sense of dimensionality that is more apparent in brighter shots composed in depth. Textures stand out in hair and haggard facial details, as well as the lived-in feel of the house in which gritty clutter wars with polished wood and clean plaster.

Audio

The uncompressed LPCM 2.0 mono track, on the other hand, is flawless, from the clear and sharp delivery of pointed dialogue muttered or bellowed, to the low foghorn that bedevils the sleep of the characters. Optional English HoH subtitles are also provided.

Extras

While the Olive Films Blu-ray was barebones, the Eureka edition includes an audio commentary by film historian Scott Harrison who covers the publication history of the play and its Swedish premiere, the autobiographical aspects in-depth (including O'Neill's actor father and his scandalous reputation), and the author's childhood and his career as a playwright. In his discussion of the film, Harrison points out the ways in which Lumet tried to open it up and his visual innovations, as well as subtle changes to the source material, but he also criticizes Lumet's neglect of the certain other aspects of the play important to establishing how far the family had deteriorated emotionally at the point in which the play starts (noting how their passion for books apparent in the play is reduced to set decoration clutter that makes little impression apart from the characters' literary quotations and mocking of one another's literary tastes). "Sidney Lumet's Stage Adaptations" (31:10) is an exhaustive audio essay by film historian Lee Gambin who traces out certain themes that run throughout Lumet's choice of theatrical properties for TV and film adaptations: the sometimes violent interrogation and performance of masculinity, sexual deviancy (usually in the form of hypocrites projecting it onto the vulnerable), and the nature of power focusing more so on films like A View from the Bridge, The Offence, Child's Play, and the wonderfully perverse Deathtrap more so than Long Day's Journey into Night. The disc also includes the film's theatrical trailer (3:36).

Packaging

Housed in the case is a collector’s booklet featuring new writing on the film by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Philip Kemp. In "A Haunting in Connecticut," Heller-Nicholas looks at the play's autobiographical aspects, the changes for the film, the charge by some critics that the film is "too faithful," as well as anecdotes about Lumet and the cast (including Robards who had previously appeared in the stage production). In "Lumet's Journey Into O'Neill," Kemp looks at the play and film as approached by Lumet and Landau (including some nice information about Lumet's choice of long lenses to isolate Mary and contrasting use of wide angle lenses so that "the reality of the room kept imposing itself more and more on the other three." "Sidney Lumet on Prince of the City" by Richard Combs is a reprint of a 1982 Monthly Film Bulletin article which does not address the O'Neill adaptation but does shed light on the challenge for Lumet of defining a visual style for each production.

Overall

A screen adaptation of a play not meant to be published or produced until a quarter of a century after the author's death, Long Day's Journey into Night hurls its audience into the thick of raw emotions with which its author had not reconciled during his lifetime.

|

|||||

|