|

|

The Film

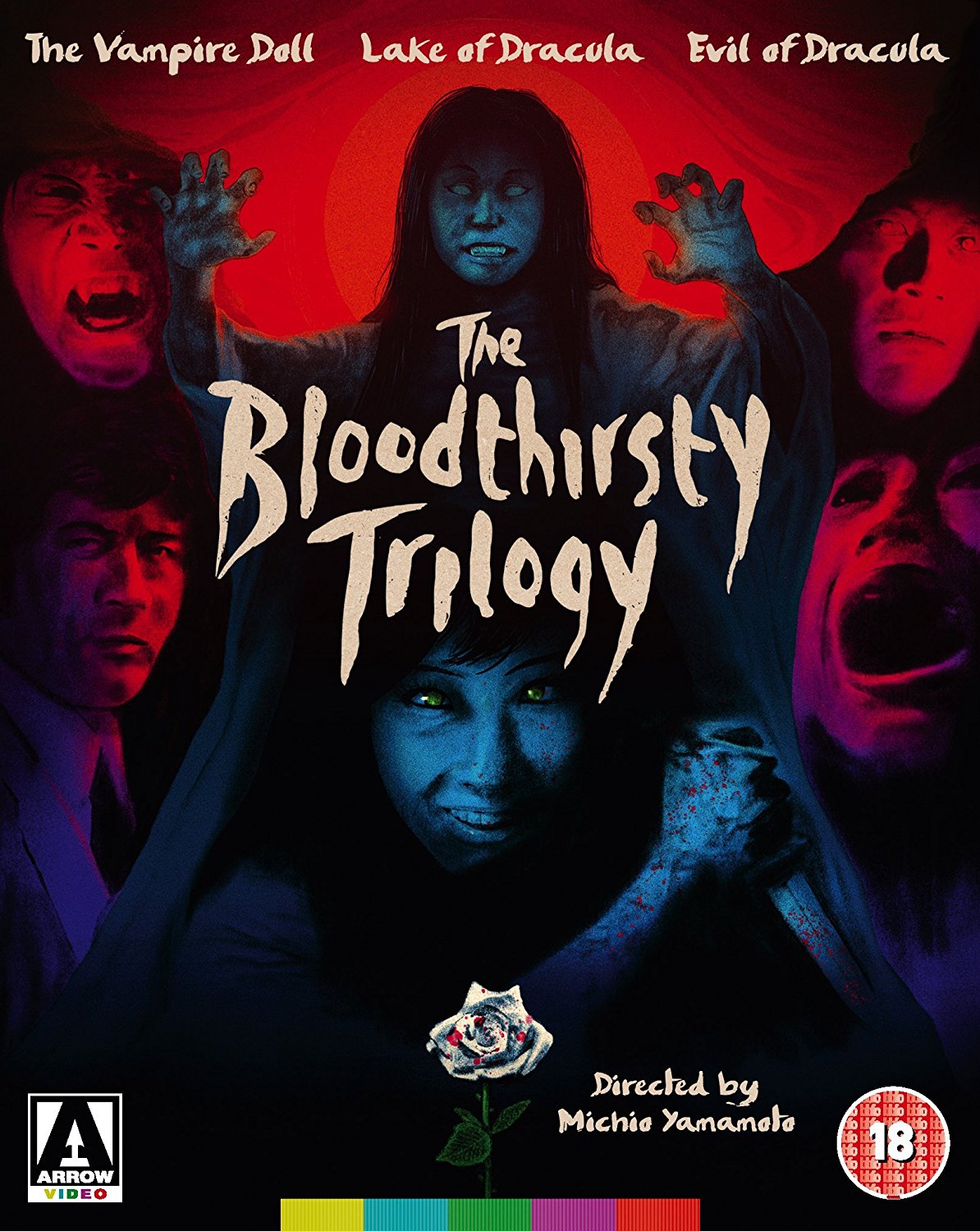

The Bloodthirsty Trilogy The Bloodthirsty Trilogy

The three films in Arrow’s ‘Bloodthirsty Trilogy’ are vampire pictures made by director Yamamoto Michio for Toho Studios. The first film in the series, The Vampire Doll (1970), has been known variously as Legacy of Dracula, Bloodsucking Doll, Fear of the Ghost House, The Night of the Vampire and The Ghost Mansion’s Horror. The second film, Lake of Dracula (1971), was also released as Dracula’s Lust for Blood, Japula(!) and Bloodthirsty Eyes. The third picture, Evil of Dracula (1974) also had an alternative English language title, Bloodthirsty Rose. Rarely seen outside Japan, these three films look sideways at the colour Gothic horror pictures made in Europe and America during the 1960s; in particular, Yamamoto’s three vampire films owe a noticeable debt to the vampire pictures of Hammer, with recognisable elements of Terence Fisher’s Dracula (1958) and Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1965), for example, working their way into Yamamoto’s vampire films by way of homage. The second film in the series, Lake of Dracula, owes a particularly noticeable debt to Fisher’s Brides of Dracula (1960), with its story of a vampire who is kept prisoner by his own family.  In The Vampire Doll, a young man, Sagawa Kazuhiko (Nakamura Atsuo), travels from Tokyo to the remote house of his girlfriend Nonomura Yuko’s (Kobayashi Yukiko) family. Kazuhiko has been away, studying in America for three years. However, upon his arrival Kazuhiko is told by Yuko’s mother, Shidu (Minakaze Yoko), that Yuko perished in a car accident. Kazuhiko accepts Shidu’s offer of a room for the evening, but in the middle of the night he hears the sound of a woman sobbing. Kazuhiko investigates, finding himself in Yuko’s bedroom, where he discovers a pale, vacant Yuko in a wardrobe. Kazuhiko is attacked and knocked unconscious. The next morning, Kazuhiko awakens on his bed, wondering if the events of the previous night were a dream. He confronts Shidu, but she tells him simply that ‘Yuko is not with us anymore’. In The Vampire Doll, a young man, Sagawa Kazuhiko (Nakamura Atsuo), travels from Tokyo to the remote house of his girlfriend Nonomura Yuko’s (Kobayashi Yukiko) family. Kazuhiko has been away, studying in America for three years. However, upon his arrival Kazuhiko is told by Yuko’s mother, Shidu (Minakaze Yoko), that Yuko perished in a car accident. Kazuhiko accepts Shidu’s offer of a room for the evening, but in the middle of the night he hears the sound of a woman sobbing. Kazuhiko investigates, finding himself in Yuko’s bedroom, where he discovers a pale, vacant Yuko in a wardrobe. Kazuhiko is attacked and knocked unconscious. The next morning, Kazuhiko awakens on his bed, wondering if the events of the previous night were a dream. He confronts Shidu, but she tells him simply that ‘Yuko is not with us anymore’.

At night, Kazuhiko believes that he sees Yuko in the garden. She is dressed in white. He investigates and finds Yuko’s headstone before encountering Yuko herself. She begs him to kill her. In the city, Kazuhiko’s sister Keiko (Matsuo Kayo) and her fiancé Hiroshi (Nakao Akira) become concerned about Kazuhiko’s whereabouts when he doesn’t return home. They decide to drive out to Yuko’s home. When they arrive, Shidu tells them that Kazuhiko left four days prior. However, Keiko is suspicious and insists to Hiroshi that they stay and investigate her brother’s disappearance. When their car is immobilised, they accept Shidu’s offer of a room for the night.  At night, they hear the same weeping Kazuhiko heard during his first night in the house. Hiroshi investigates but encounters Shidu; meanwhile, Keiko is shocked to see her sister. However, Hiroshi later suggests that Keiko imagined this, and that Yuko cannot possibly be alive. At night, they hear the same weeping Kazuhiko heard during his first night in the house. Hiroshi investigates but encounters Shidu; meanwhile, Keiko is shocked to see her sister. However, Hiroshi later suggests that Keiko imagined this, and that Yuko cannot possibly be alive.

Keiko and Hiroshi investigate in the nearby town, speaking to the local registrar, who tells them that the Nonomura family is ‘cursed by the God of Death’: twenty years prior, Shidu’s family were attacked and killed. Only Shidu was left alive, and nine months later she gave birth to Yuko. Rumour has it that Yuko was the product of a union between Shidu and her family’s murderer. Keiko and Hiroshi also speak with the local doctor, Yamaguchi (Usami Jun), who tells them a story of when he saw a ghost during the war. Outside, Hiroshi meets the local gravedigger, who tells Hiroshi that he is willing to exhume Yuko’s coffin – for a price. Hiroshi and the gravedigger travel to the cemetery and dig up the coffin, only to find a mannequin in it instead of the body of Yuko. Hiroshi is soon attacked by Shidu’s servant, Genzo (Takashina Kaku). Meanwhile, Keiko has been locked in a room by Shidu.  Lake of Dracula begins with a young girl, five year old Kashiwagi Akiko, and her dog Leo wandering the coastal landscape. They discover a cave and, passing through it, an isolated house beyond it. Seeking sanctuary in the building, Akiko and Leo discover it to be populated by vampires! Lake of Dracula begins with a young girl, five year old Kashiwagi Akiko, and her dog Leo wandering the coastal landscape. They discover a cave and, passing through it, an isolated house beyond it. Seeking sanctuary in the building, Akiko and Leo discover it to be populated by vampires!

Eighteen years later, Akiko (Fujita Midori) is now a young adult living with her sister Natsuko (Emi Sanae) in a house by Lake Fujimi. Both are students, but Akiko is also a budding painter, her current canvas filled with a vivid depiction of a glaring eye. Akiko’s fiancé is Saeki Takashi (Takahashi Choei), a junior doctor at the hospital. She is neighbours with Kyusaku (Takashina Kaku), the caretaker of the houses on the shore of the lake. One day, Kyusaku takes receipt of a delivery: it is a mysterious crate, which Kyusaku discovers contains a coffin. As darkness falls, Kyusaku is attacked by a vampire that was concealed within the coffin. Meanwhile, at the hospital Saeki finds himself attending to a patient who has been partially exsanguinated. The woman, Saeki is told, was found close to Lake Fujimi.  The next day, returning home after spending time with Natsuko, Akiko is dismayed to find her dog Leo missing. She searches for Leo and discovers his body close to the lake: he has been killed. She is attacked by Kyusaku, who carries Akiko’s unconscious body to his house – where she meets the vampire but is saved by two fisherman who have arrived at Kyusaku’s place in the hope of renting on of the lakeside cottages. The next day, returning home after spending time with Natsuko, Akiko is dismayed to find her dog Leo missing. She searches for Leo and discovers his body close to the lake: he has been killed. She is attacked by Kyusaku, who carries Akiko’s unconscious body to his house – where she meets the vampire but is saved by two fisherman who have arrived at Kyusaku’s place in the hope of renting on of the lakeside cottages.

At night, Natsuko encounters the vampire and is bitten by him. She returns home and, uncharacteristically, picks an argument with Akiko in front of Saeki. Later, Natsuko attempts to lure Akiko to a meeting with the vampire. After Natsuko is taken to hospital in a weakened state, Saeki attempts to help Akiko by accompanying her on a journey to find the strange house of vampires that haunts her memories and dreams.  In Evil of Dracula, a psychology teacher, Shiraki (Kurosawa Toshio), journeys from Tokyo to the isolated Seimei School for girls. Arriving at the school, he is met by the principal (Kishida Shin), whose wife died two days prior in a car accident. The principal has kept his wife’s body in the basement of the school, something which the principal insists is ‘an old local custom’. In Evil of Dracula, a psychology teacher, Shiraki (Kurosawa Toshio), journeys from Tokyo to the isolated Seimei School for girls. Arriving at the school, he is met by the principal (Kishida Shin), whose wife died two days prior in a car accident. The principal has kept his wife’s body in the basement of the school, something which the principal insists is ‘an old local custom’.

The principal tells Shiraki that he hopes Shiraki will succeed him as the head of the school. Shiraki is surprised and humbled. He meets some of the female students, and also encounters the eccentric French master, Yoshii (Sasaki Katsuhiko), who is given to wandering the grounds quoting Baudelaire to himself. Shiraki makes an ally in the school’s doctor, Shimomura (Tanaka Kunie), who tells Shiraki that one of the students disappeared five days prior to Shiraki’s arrival. This, it seems, is a semi-regular occurrence, one or two students disappearing each year. A collector of folk tales and local lore, Shimomura tells Shiraki that the locals believe this to be a case of the ‘devil […] having his fun’. Shimomura shows Shiraki a partially exposed coffin in the local cemetery. The coffin is said to be 200 years old and belongs to a Caucasian shipwreck victim who was washed ashore and tortured owing to his Christian faith. The shipwreck victim escaped from his captors and wandered the land; starving and dehydrated, he attacked a fifteen year old girl and drank her blood. The locals caught and killed both of them, claiming them to be vampires, and buried them together in the coffin which, Shimomura shows Shiraki, is now empty.  During his first night at the school, Shiraki awoke to hear the sound of a woman singing. Exploring the school, he was shocked to come face to face with a pale-faced teenaged girl in a blue negligee. Initially dismissing this encounter as a dream, Shiraki later comes to realise that the girl he saw was Keiko (Agawa Yasuko), the student who went missing from the school five days before Shiraki’s arrival. During his first night at the school, Shiraki awoke to hear the sound of a woman singing. Exploring the school, he was shocked to come face to face with a pale-faced teenaged girl in a blue negligee. Initially dismissing this encounter as a dream, Shiraki later comes to realise that the girl he saw was Keiko (Agawa Yasuko), the student who went missing from the school five days before Shiraki’s arrival.

Meanwhile, the principal, a vampire, has attacked one of Keiko’s friends, Kyoko (Aramaki Keiko). The other students are returning home for the holidays, but three roommates – Kyoko, Yukiko (Ota Mio) and Kumi (Mochizuki Mariko) – are left behind. At night, Kyoko lures Yukiko to the vampire before throwing herself off a balcony. His suspicions already aroused, Shimomura follows Yukiko to a nighttime meeting in the woods with the principal. However, Shimomura is attacked by the vampire and disappears. Only Shiraki and Kumi are left at the school; they must unravel the mystery and survive the vampires.  Yamamoto’s Hammer-like vampire pictures weren’t alone in ‘localising’ the paradigms of 1960s Western horror films for Japanese audiences: Sato Hajime’s House of Terrors (1965), for example, was very much influenced by the monochrome Italian Gothic pictures of directors such as Mario Bava, Riccardo Freda and Antonio Margheriti. Though with a strong narrative debt to Bram Stoker’s Dracula and its various film adaptations (the Dracula-Renfield relationship recurs throughout these films, for example), Yamamoto’s vampire pictures play fast and loose with vampire lore. Yamamoto’s Hammer-like vampire pictures weren’t alone in ‘localising’ the paradigms of 1960s Western horror films for Japanese audiences: Sato Hajime’s House of Terrors (1965), for example, was very much influenced by the monochrome Italian Gothic pictures of directors such as Mario Bava, Riccardo Freda and Antonio Margheriti. Though with a strong narrative debt to Bram Stoker’s Dracula and its various film adaptations (the Dracula-Renfield relationship recurs throughout these films, for example), Yamamoto’s vampire pictures play fast and loose with vampire lore.

As Jim Harper has suggested, ‘[m]any Japanese vampire films can be unsatisfying for Western audiences, primarily because their creators are either unaware of or disinterested in the various aspects of Western vampire lore’ (Harper, 2016: 27). Where Chinese vampire films, for example, offered a unique ‘spin’ on the subgenre of vampire fiction by working into their narratives elements of local lore (for example, the jiangshi/‘hopping’ vampires found in a number of Chinese films, most famously the Mr Vampire pictures), Japanese vampire pictures ‘had no indigenous [vampire-related] traditions to draw upon’ and thus often saw ‘writers […] creat[ing] their own mythos or taking on concepts from elsewhere’ (ibid.). As a consequence, Yamamoto’s vampire pictures offer strange variations on the paradigms of imported Western vampire films, in particular owing a strong debt to Terence Fisher’s Dracula films. The vampires in Evil of Dracula, for example, seem to use vampirism as a means of transferring their essence from an aging body to a younger body; the plot involves the school principal (a vampire) and his wife (also a vampire) attempting to find new ‘host’ bodies. The principal does this by biting his female victims (his students) on the breast, an act which leads them to falling under his spell. Meanwhile, in Vampire Doll, the concept of vampirism has little impact on the plot – which is essentially a haunted house story with the vampire motif bolted on to it. There are no fangs and no blood drinking; Yuko, reanimated as a ghoul, instead uses a dagger to slash the throats of her victims. Throughout all three films, none of the vampires seem to have particular problems with sunlight, though most of them are dispatched in ways that are familiar from European vampire films (a stake through the heart, in particular). Two of the films feature moments which mirror the denouement of Terence Fisher’s The Horror of Dracula, with the vampires turning to ash in front of the camera. As Jim Harper notes, ‘this unorthodox approach can sometimes be refreshing, bringing in welcome changes to the tradition-bound world of vampire legends’ (ibid.). This would be especially noticeable in the latter days of Hammer’s vampire cycle, during which the studio was recycling the motifs of Terence Fisher’s early Dracula films ad infinitum or trying to do something new and failing miserably (for example, by placing Dracula in the present day in Alan Gibson’s Dracula A.D. 1972, 1972).  The narrative of The Vampire Doll is essentially a classic Gothic ‘old dark house’ story, of the kind that was parodied a few years later in Jim Sharman’s The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), in which young people arrive at a cursed/haunted location unaware of its history and the peril in which they have placed themselves. The sequence in which Kazuhiko hears the sobbing of the resurrected Yuko and investigates, finding Yuko concealed in a wardrobe in her room, is unsettling thanks to the use of sound and the manner in which the widescreen photography creates a sense of imbalance within the compositions, suggesting that something will at any moment leap out to attack Kazuhiko. The narrative of The Vampire Doll is essentially a classic Gothic ‘old dark house’ story, of the kind that was parodied a few years later in Jim Sharman’s The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), in which young people arrive at a cursed/haunted location unaware of its history and the peril in which they have placed themselves. The sequence in which Kazuhiko hears the sobbing of the resurrected Yuko and investigates, finding Yuko concealed in a wardrobe in her room, is unsettling thanks to the use of sound and the manner in which the widescreen photography creates a sense of imbalance within the compositions, suggesting that something will at any moment leap out to attack Kazuhiko.

Within this film, even characters that embody rationalism are willing to accept the existence of the paranormal. When Keiko and Hiroshi visit Doctor Yamaguchi, he tells them that ‘Science can’t explain occult powers. It’s not my speciality but I’m studying it. I saw a ghost myself’. Yamaguchi tells the couple of his experiences during the war, when he and some of his comrades saw the ghost of one of their fallen friends. Later in the film, it’s revealed that Yuko’s existence after death is, to some extent, a product of science: in a revelation that seems like an obvious tip of the hat to Edgar Allan Poe’s story ‘The Facts in the Case of M Valdemar’, it is revealed that at the moment of her death, Yuko was hypnotised. This is the reason why her consciousness has continued after death.  Lake of Dracula is a more traditional vampire story, with vampires that bite the throats of their victims and suck their blood in a way that is recognisable from Western vampire pictures. The film even features a Renfield-like figure, in the form of Kyusaku, the kindly caretaker of the lakeside cottages who is the first character to be ‘turned’ by the vampire. Lake of Dracula is a more traditional vampire story, with vampires that bite the throats of their victims and suck their blood in a way that is recognisable from Western vampire pictures. The film even features a Renfield-like figure, in the form of Kyusaku, the kindly caretaker of the lakeside cottages who is the first character to be ‘turned’ by the vampire.

The film takes place in northern Honshu. Its protagonist Akiko’s work as an artist enables the script to confront some of the overt Freudian symbolism of vampire narratives through various characters’ responses to her strange painting and her recurring dream/memory in which Akiko, as a five year old girl, encounters the vampires in an isolated house by the coast. The painting itself, and its use within the narrative, recalls Abel Ferrara’s use of his protagonist Reno’s painting of a buffalo in the later film Driller Killer, 1979; like Reno’s buffalo painting, Akiko’s painting is a vivid swirl of primary colours with a focal point that is an eye that functions like a black hole, drawing the viewer into it. Neither Reno nor Akiko can explain their fascination with their respective paintings: ‘Don’t ask me’, Akiko responds when her sister asks her what the painting means, ‘I don’t know. I can’t get it out of my head, that eye!’ Akiko’s sister Natsuko decodes Akiko’s recurring dream in psychoanalytic terms, asserting that Akiko’s ‘experience [of] terror at a young age’ is the reason she ‘create[s] illusions of hypothetical enemies’. Meanwhile, in a later sequence, the vampire visits Akiko and reveals himself to be something of an art critic, examining Akiko’s painting and asserting, ‘Don’t be afraid, young lady. I’ve taken a liking to you and that picture of yours. A first-rate work of art. It’s wonderful. The fear felt by the artist is portrayed so vividly’. As in The Vampire Doll, the first character to mention the possibility of vampires is a man of science, a rationalist: it is Saeki, Akiko’s lover and a junior doctor, who makes the connection between the strange events and vampirism, noting that ‘These people that you know, they were all transformed into devils. The marks on their necks, the loss of blood. There’s only one answer: a vampire. Some of those legends about vampires and cannibals, they sound like true stories. Even nowadays, you read about numerous cases of cannibalism […] Shortly after they die, they become vampires themselves. Only fire or a stake through the heart can stop them’.  As Jim Harper notes, Evil of Dracula has some superficial similarities with Jimmy Sangster’s Lust of the Vampire (1971), in terms of its setting in a girls’ school (Harper, op cit.: 27). This film is the most explicit of the three pictures. The vampire bites his female victims (students at a girls’ school, no less) on the breast, and the filmmakers show us these wounds in close-up, with a glimpse of nipple in each instance. The school itself is, as Jim Harper notes, ‘a hothouse of sexual tension and adolescent hormones’ in which the girls openly flirt with their male teachers and talk about sleeping with them (ibid.: 28). The plot has the slight whiff, presumably completely unintentionally, of the wartime Will Hay comedy The Ghost of St Michaels (Marcel Varnel, 1941), in which Hay’s schoolteacher is hired by a school relocated to the haunted Dunbain Castle on the Isle of Skye. Additionally, at times Evil of Dracula borders on the tone of a Carry On… film, in terms of the flirtatious behaviour between the female students and the male teachers: when Shiraki first meets Yukiko, she flirts with him outrageously, telling him, ‘Sir, if you let me stay out after curfew, maybe we could go out on a date’. The film is also much more action-oriented than the two pictures which preceded it, the vampire’s growling, feral nature recalling the animalistic behaviour of Christopher Lee’s Dracula in Dracula: Prince of Darkness. As Jim Harper notes, Evil of Dracula has some superficial similarities with Jimmy Sangster’s Lust of the Vampire (1971), in terms of its setting in a girls’ school (Harper, op cit.: 27). This film is the most explicit of the three pictures. The vampire bites his female victims (students at a girls’ school, no less) on the breast, and the filmmakers show us these wounds in close-up, with a glimpse of nipple in each instance. The school itself is, as Jim Harper notes, ‘a hothouse of sexual tension and adolescent hormones’ in which the girls openly flirt with their male teachers and talk about sleeping with them (ibid.: 28). The plot has the slight whiff, presumably completely unintentionally, of the wartime Will Hay comedy The Ghost of St Michaels (Marcel Varnel, 1941), in which Hay’s schoolteacher is hired by a school relocated to the haunted Dunbain Castle on the Isle of Skye. Additionally, at times Evil of Dracula borders on the tone of a Carry On… film, in terms of the flirtatious behaviour between the female students and the male teachers: when Shiraki first meets Yukiko, she flirts with him outrageously, telling him, ‘Sir, if you let me stay out after curfew, maybe we could go out on a date’. The film is also much more action-oriented than the two pictures which preceded it, the vampire’s growling, feral nature recalling the animalistic behaviour of Christopher Lee’s Dracula in Dracula: Prince of Darkness.

Like Stoker’s Dracula, which frames vampirism as a ‘foreign’ threat that is imported into England from Eastern Europe, Yamamoto’s three vampire pictures are linked by a depiction of vampirism as a foreign threat imported from the West. In The Vampire Doll, the ‘vampire’, Yuko, is a descendant of a family of diplomats, the Nonomura’s home bedecked in Western furnishings (‘It’s a splendid Western-style house’, Hiroshi notes to Shidu when he and Keiko arrive at the Nonomura home); the suggestion is that her vampirism is as much an import as the Western objects in the house. The vampire in Lake of Dracula is the descendant of immigrants from the West who brought with them a benign form of vampirism, which escalated once their Japan-born son became more aggressive in his pursuit of blood at the age of twenty-five. In Evil of Dracula, local legend has it that the vampiric curse was brought to the territory by a Caucasian victim of a shipwreck who was tortured by the locals owing to his Christianity, at a time when being Christian was outlawed in Japan. The foreigner spat upon the cross and denounced God before becoming ‘a demon’. Breaking free from his captives, he wandered the arid landscape; driven half-mad by starvation and dehydration, he drank the blood of a fifteen year old girl and became a vampire. His curse then passed down through generation after generation of principals at the girls’ school, vampirism used as a means to transfer the ‘soul’ or ‘spirit’ of the vampire into younger ‘host’ bodies. Like Stoker’s Dracula, which frames vampirism as a ‘foreign’ threat that is imported into England from Eastern Europe, Yamamoto’s three vampire pictures are linked by a depiction of vampirism as a foreign threat imported from the West. In The Vampire Doll, the ‘vampire’, Yuko, is a descendant of a family of diplomats, the Nonomura’s home bedecked in Western furnishings (‘It’s a splendid Western-style house’, Hiroshi notes to Shidu when he and Keiko arrive at the Nonomura home); the suggestion is that her vampirism is as much an import as the Western objects in the house. The vampire in Lake of Dracula is the descendant of immigrants from the West who brought with them a benign form of vampirism, which escalated once their Japan-born son became more aggressive in his pursuit of blood at the age of twenty-five. In Evil of Dracula, local legend has it that the vampiric curse was brought to the territory by a Caucasian victim of a shipwreck who was tortured by the locals owing to his Christianity, at a time when being Christian was outlawed in Japan. The foreigner spat upon the cross and denounced God before becoming ‘a demon’. Breaking free from his captives, he wandered the arid landscape; driven half-mad by starvation and dehydration, he drank the blood of a fifteen year old girl and became a vampire. His curse then passed down through generation after generation of principals at the girls’ school, vampirism used as a means to transfer the ‘soul’ or ‘spirit’ of the vampire into younger ‘host’ bodies.

Again, as with the previous two films, Evil of Dracula makes its most stereotypically ‘rational’ character, Doctor Shimomura, the first character to suggest a supernatural reason for the disappearances of the students. Shimomura tells Shiraki that ‘The old people round here say that the devil’s having his fun’, and he takes the new teacher to the local graveyard where the 200 year old coffin of the Caucasian shipwreck survivor lies partially exposed. Shimomura is a collector of folklore, telling Shiraki that there are many local stories of vampires.

Video

All three films are presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The three films were all photographed in Tohoscope and are presented here in their original 2.35:1 aspect ratios. The Vampire Doll is contained on disc one and takes up 19Gb of space on the disc, running for 71:01 mins. Lake of Dracula and Evil of Dracula are housed on disc two. With its running time of 81:34 mins, Lake of Dracula takes up 23Gb of space on the disc, and Evil of Dracula runs for 82:47 mins and fills 20Gb of space. All three films are presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. The three films were all photographed in Tohoscope and are presented here in their original 2.35:1 aspect ratios. The Vampire Doll is contained on disc one and takes up 19Gb of space on the disc, running for 71:01 mins. Lake of Dracula and Evil of Dracula are housed on disc two. With its running time of 81:34 mins, Lake of Dracula takes up 23Gb of space on the disc, and Evil of Dracula runs for 82:47 mins and fills 20Gb of space.

Arrow’s promotional material for this release says that the three films were transferred ‘from original film elements’ but doesn’t specify what type of film elements these were, though from the evidence here these wouldn’t seem to be negative-sourced transfers. The HD masters were provided to Arrow by Toho. All three films were shot within a few years of each other, seemingly on identical (or near-identical stock), and the video presentations of all three pictures are very similar. Colours are for the most part naturalistic, though there is some expressive use of red lighting and tinting in Lake of Dracula (via the flashbacks and dream sequences) and Evil of Dracula (in a darkroom-set scene), and a couple of sequences have a deliberately desaturated palette (the flashbacks to the shipwreck victim’s trek through the desert in Lake of Dracula, for example). Little to no damage is present throughout all three films. Contrast levels are pleasing, with midtones showing a strong sense of definition. Black levels seem elevated in the nighttime sequences (see the large screengrabs below). Highlights are evenly balanced throughout. There’s some day-for-night footage which looks slightly funky, but probably always did. Detail is good throughout, with fine detail present in closeups – but sometimes there’s a slightly gauzey look which, combined with a relatively coarse structure, suggests these presentations were sourced from positive film elements rather than the negatives. (There are also some shots in all three films which seem out of focus – an issue of the original production rather than a ‘fault’ of this HD presentation.) The encodes-to-disc seem fine, the presentations retaining the structure of 35mm film. In all, these are pleasing presentations of the three films though with some potential room for improvement. The Vampire Doll

Lake of Dracula

Evil of Dracula

For full-size screengrabs from all three films, please scroll down to the bottom of this review.

Audio

All three films feature LPCM 1.0 tracks, in Japanese. These audio tracks are clean and clear, free from distortion, and show good range. Optional English subtitles are included. These are easy to read and free from any distracting errors. Strangely, despite not being listed in the menus or on the documentation accompanying this release, both Lake of Dracula and Evil of Dracula contain the films’ English dubs, also in LPCM 1.0. These dubs aren’t bad at all, and though purists will prefer the Japanese language tracks, they offer an interesting alternative way to view the film. The dub tracks are bassier than the Japanese tracks, with a slightly compressed range, but they’re certainly listen-able.

Extras

DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

The Vampire Doll (71:01) - Kim Newman on The Bloodthirsty Trilogy (16:06). Newman, as affable as ever, discusses the production history of these films and reflects on their relationship with Western vampire pictures. Newman considers the films in the context of other contemporaneous Japanese genre pictures and suggests that though the films didn’t really change the paradigms of Japanese horror films, owing to the fact that they were outnumbered by more traditional Japanese genre pictures, they offered an interesting sidebar in the history of Japanese horror cinema. - Trailers: The Vampire Doll (2:04); Lake of Dracula (2:12); Evil of Dracula (2:22). - Stills Galleries: The Vampire Doll (20 images); Lake of Dracula (9 images); Evil of Dracula (21 images). DISC TWO: Lake of Dracula (81:34) Evil of Dracula (82:47) - Trailers: The Vampire Doll (2:04); Lake of Dracula (2:12); Evil of Dracula (2:22).

Overall

Though these films owe an obvious debt to Hammer’s vampire pictures, in particular, there are elements within Yamamoto’s trilogy of vampire films that anticipate later films: for example, the taxi ride in the opening moments of The Vampire Doll is strikingly similar to the Susy Banyon’s taxi ride at the start of Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977), and there’s a chase through the woods in Evil of Dracula in which the ‘victim’ is framed in long shot, the camera dollying alongside her, which also resembles a moment from Suspiria. The films offer strange riffs on the paradigms of the vampire picture; in terms of borrowing the iconography of the Hammer vampire films (including elements of Christopher Lee’s animalistic performance from Dracula: Prince of Darkness, in particular), Yamamoto’s vampire films are familiar. But in other ways, they are utterly new and strange: they allude to recognisable elements of vampire lore but twist these in new directions. They are also genuinely unsettling at times, Yamamoto’s use of both sound and the widescreen frame creating suspense during those sequences in which the films’ characters explore isolated, creepy locations. Though these films owe an obvious debt to Hammer’s vampire pictures, in particular, there are elements within Yamamoto’s trilogy of vampire films that anticipate later films: for example, the taxi ride in the opening moments of The Vampire Doll is strikingly similar to the Susy Banyon’s taxi ride at the start of Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977), and there’s a chase through the woods in Evil of Dracula in which the ‘victim’ is framed in long shot, the camera dollying alongside her, which also resembles a moment from Suspiria. The films offer strange riffs on the paradigms of the vampire picture; in terms of borrowing the iconography of the Hammer vampire films (including elements of Christopher Lee’s animalistic performance from Dracula: Prince of Darkness, in particular), Yamamoto’s vampire films are familiar. But in other ways, they are utterly new and strange: they allude to recognisable elements of vampire lore but twist these in new directions. They are also genuinely unsettling at times, Yamamoto’s use of both sound and the widescreen frame creating suspense during those sequences in which the films’ characters explore isolated, creepy locations.

These are certainly very interesting films, and they have been difficult to see – at least, in their original aspect ratios – for a number of years. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of these three pictures amends this, offering solid presentations of all three films alongside an illuminating albeit brief interview with Kim Newman. The original promotional material, especially the stark monochrome stills, included here is also interesting. Horror fans will find this release to be a pretty essential purchase. References: Harper, Jim, 2016: ‘Bloodthirsty Films’. In: Murgula, Salvador Jimenez (ed), 2016: The Encyclopedia of Japanese Horror Films. London: Rowman and Littlefield: 26-8 Please click to enlarge: The Vampire Doll

Lake of Dracula

Evil of Dracula

|

|||||

|