|

|

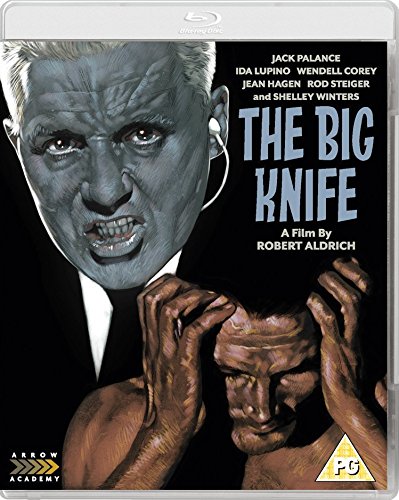

Big Knife (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (9th September 2017). |

|

The Film

The Big Knife (Robert Aldrich, 1955) The Big Knife (Robert Aldrich, 1955)

Made immediately after fiercely independent filmmaker Robert Aldrich’s subversive Mickey Spillane adaptation Kiss Me Deadly (1955), The Big Knife (1955) was an adaptation of Clifford Odets’ stage play, originally written in 1948; taken together, these two pictures offer a one-two punch to the ‘culture industry’, Kiss Me Deadly offering a satirical depiction of Cold War paranoia through the lens of Spillane’s lurid pulp noir-fantasy character of Mike Hammer, and The Big Knife delivering a direct attack on Hollywood studio system. Aldrich’s subsequent film, Attack! (1956) – on which the director worked once again with Jack Palance, who played the lead role in The Big Knife – was equally subversive and was also based on a play, this time by Norman Brooks. Aldrich later reflected that he believed these three films to be among his best, though they were not profitable and Aldrich was paid next to nothing for his work on them (Aldrich, in Silver, 1970: 56). Charlie Castle (Jack Palance) has been a Hollywood star for almost a decade. Castle is known for playing tough guy roles on screen, but at home he is estranged from Marion (Ida Lupino), the wife he still loves, and his young son Billy (Mike Winkelman). Marion dislikes Charlie’s association with sleazy big-shot Hollywood producer Stanley Hoff (Rod Steiger) and vows that if Charlie agrees to sign a new seven year contract with Hoff’s production company, Hoff-Federated, she will not return to the marital home.  Charlie was once an idealist, committed to films with meaning; but working with Hoff, he has become a star in commercial pictures, and Marion suggests that because of this, Charlie has lost touch with who he is – or was. Marion is on the cusp of forming a new relationship with Charlie’s friend Hank (Wesley Addy), a writer whose work is defiantly uncommercial. Charlie was once an idealist, committed to films with meaning; but working with Hoff, he has become a star in commercial pictures, and Marion suggests that because of this, Charlie has lost touch with who he is – or was. Marion is on the cusp of forming a new relationship with Charlie’s friend Hank (Wesley Addy), a writer whose work is defiantly uncommercial.

Charlie is also surrounded by his friend Buddy Bliss (Paul Langton), who spent ten months in prison for a crime Charlie committed, his personal trainer Nick (Nick Cravat), his agent Nat (Everett Sloane) and his servant Russell (Bill Walker). A studio ‘troubleshooter’ and publicity man, Buddy advises Charlie on his handling of gossip columnist Patty Benedict (Ilka Chase). Charlie is trying to keep his separation from Marion from finding its way into print. When Hoff arrives at Charlie’s home, accompanied by his associate Smiley Cory (Wendell Corey), Charlie attempts to put an end to their relationship. However, he’s pressured into accepting the new seven year contract with Hoff-Federated after a highly emotional Hoff reminds Charlie of the secret they share. Later, after drinking himself into a stupor Charlie is seduced by his friend Buddy’s wife Connie (Jean Hagen). A new problem emerges: an aspiring starlet, Dixie Evans (Shelley Winters), was in the car with Charlie the night of the incident for which Buddy took the flack. Unhappy with Hoff, who has contracted Evans to his studio to keep her quiet but who uses Evans solely to ‘entertain’ prospective exhibitors, Evans threatens to blag about both Charlie’s transgression and secrets of Hoff’s. Smiley attempts to commission Charlie with the task of murdering Evans, but Charlie resists. This causes more friction between Charlie and Hoff; and when Buddy finds out about Charlie’s fling with Connie, Charlie’s house of cards threatens to come tumbling down.  Charlie’s prior ‘indiscretion’, the incident for which Buddy spent time in prison, is alluded to in the dialogue from an early stage of the picture, but only about an hour into the film is the exact nature of this event revealed: Charlie was apparently involved in a ‘hit and run’ in which a child, a young boy, was killed, and in order to protect Charlie’s career, his friend Buddy took the rap, claiming that he ‘borrowed’ Charlie’s car before running the child over. Hoff-Federated has helped to conceal the truth of this event from the press, thus preventing Charlie’s career from being ruined, but Dixie’s bitterness at her treatment by Hoff-Federated threatens to make this information, and other shameful secrets buried by the studio, public. Charlie’s prior ‘indiscretion’, the incident for which Buddy spent time in prison, is alluded to in the dialogue from an early stage of the picture, but only about an hour into the film is the exact nature of this event revealed: Charlie was apparently involved in a ‘hit and run’ in which a child, a young boy, was killed, and in order to protect Charlie’s career, his friend Buddy took the rap, claiming that he ‘borrowed’ Charlie’s car before running the child over. Hoff-Federated has helped to conceal the truth of this event from the press, thus preventing Charlie’s career from being ruined, but Dixie’s bitterness at her treatment by Hoff-Federated threatens to make this information, and other shameful secrets buried by the studio, public.

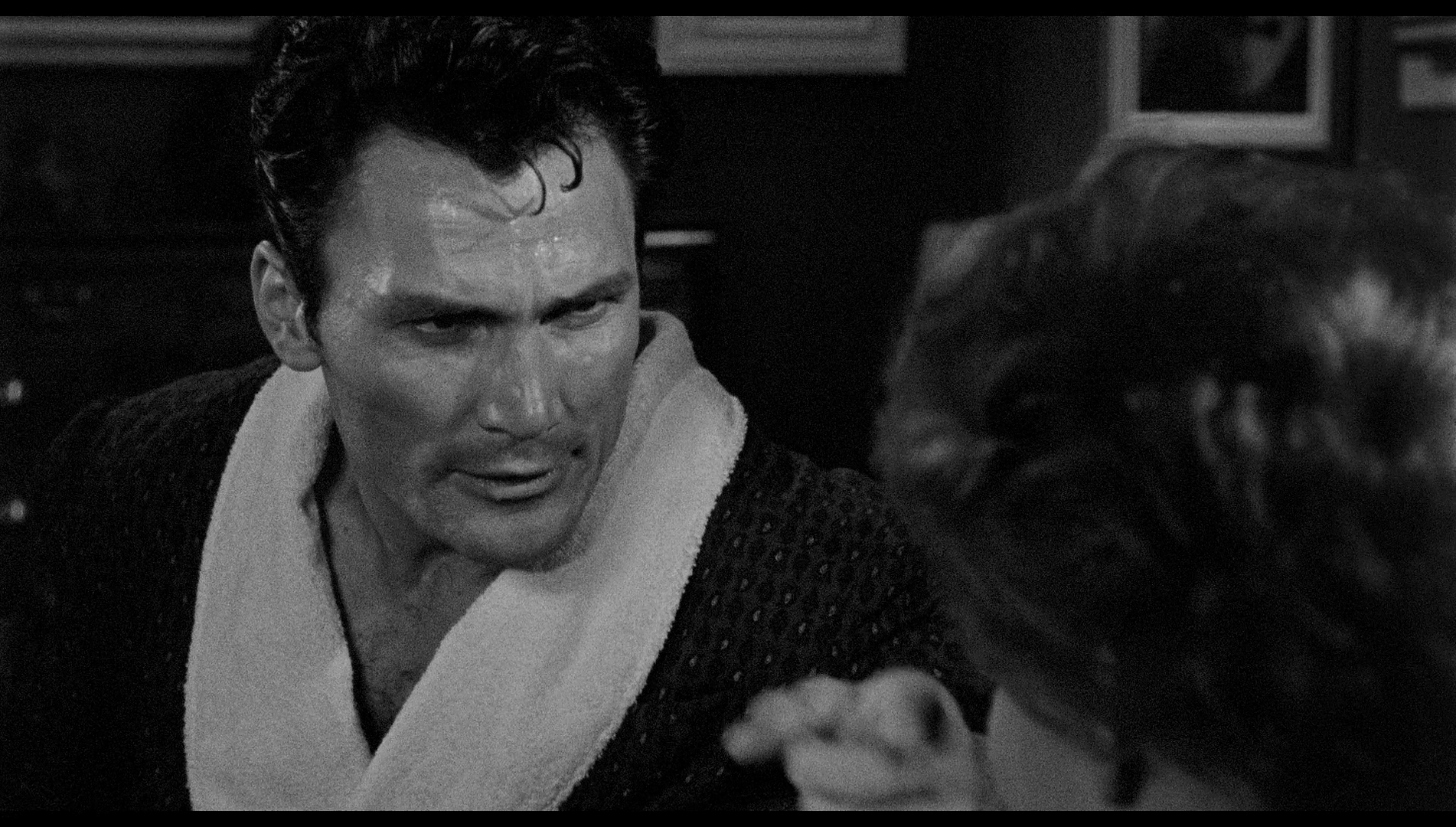

This incident has allowed Hoff to keep Charlie on a string, and Hoff pressures Charlie into signing a new seven year contract with threats that if Charlie refuses to sign, Hoff will make the truth of this incident public. Hoff’s contract with Charlie is framed as a Faustian pact, Marion observing that ‘It’s a fabulous deal, but it’s for seven years and the life that goes with it. Or should I say, the death that goes with it?’ Hoff’s subtle sexualisation of Charlie suggests that there is more to their ‘contract’ than Charlie’s box office appeal. When Hoff enters the film for the first time and speaks with Charlie, he runs his hand over the bathrobe that Charlie is wearing before patting Castle’s rump: ‘That’s a pleasure to feel next to your skin’, Hoff asserts, shortly afterwards telling Charlie that ‘I need your physical presence on the lot. I need your body, not your goodwill’. Marion seems to be implying that Charlie’s contract with Hoff will entail more than simply acting in Hoff’s lowbrow pictures. This is a reading of Hoff’s relationship with Charlie that seems fixed by Nat’s insistence on calling Charlie ‘darling’, and Smiley’s use of the feminine term ‘kitty’ to address the actor. (‘Life’s a queer little man, kitty’, Smiley tells Charlie at one point in the film.)  Hoff’s treatment of Dixie Evans is also subtly disturbing. Evans has been contracted with Hoff-Federated as a means of keeping her quiet about her knowledge of the car accident in which the child was killed – and for which Buddy took the blame. However, Evans is unhappy that Hoff hasn’t made her a film star. Instead, she tells Charlie, Hoff uses her as part of a stable of women tasked with ‘entertaining’ prospective exhibitors for his pictures. When Smiley asks Charlie to ‘remove’ Evans, it seems more for her knowledge of Hoff’s secrets than her threat to blag about Charlie’s role in the hit-and-run. Of Hoff, Evans tells Charlie he ‘Call[s] me “child” one moment, and then without changing his face….’ She avoids elaborating on the specificities of Hoff’s behaviour, but the elliptical dialogue speaks volumes. ‘You don’t see these people from the bottom like I do, Charlie’, she tells Castle, adding that ‘I know where to stop; but I don’t see any reason to make it easy on them’. Hoff’s treatment of Dixie Evans is also subtly disturbing. Evans has been contracted with Hoff-Federated as a means of keeping her quiet about her knowledge of the car accident in which the child was killed – and for which Buddy took the blame. However, Evans is unhappy that Hoff hasn’t made her a film star. Instead, she tells Charlie, Hoff uses her as part of a stable of women tasked with ‘entertaining’ prospective exhibitors for his pictures. When Smiley asks Charlie to ‘remove’ Evans, it seems more for her knowledge of Hoff’s secrets than her threat to blag about Charlie’s role in the hit-and-run. Of Hoff, Evans tells Charlie he ‘Call[s] me “child” one moment, and then without changing his face….’ She avoids elaborating on the specificities of Hoff’s behaviour, but the elliptical dialogue speaks volumes. ‘You don’t see these people from the bottom like I do, Charlie’, she tells Castle, adding that ‘I know where to stop; but I don’t see any reason to make it easy on them’.

Aldrich suggested the character of Hoff was a combination of elements of Senator McCarthy and studio heads Harry Cohn and Louis B Mayer – particularly the latter’s tendency to become highly emotional to the point of tears. Aldrich subsequently signed to Columbia, and it took some time for Cohn to realise Aldrich had directed The Big Knife. When that realisation struck, Cohn confronted Aldrich, saying, ‘You son of a bitch. If I’d known that [you directed that picture] you would never have been here’ (Alrich, quoted in Silver, op cit.: 59). The Big Knife confronts the tension within American cinema between movies as ‘art’ and as ‘products’ with commercial potential. The dialogue deals with this theme explicitly, sometimes threatening to become didactic in its exploration of this notion. ‘You know this industry is capable of turning out some good pictures, pictures with guts and meaning’, Charlie tells Marion. (Along with Kiss Me Deadly and Attack!, its closest neighbours in the career of Aldrich, The Big Knife is one such picture.)  The film establishes the context of its story, a world of privilege and rapacious wealth, from the outset. A narrator (Richard Boone) introduces the Bel Air setting with the words ‘If you work in the motion picture industry and are successful, this well-tended suburb of Hollywood is where you will probably make your home. Failure is not permitted here’. The narrator adds: ‘Charlie Castle is a man who sold out his dreams; but he can’t forget them’. The film establishes the context of its story, a world of privilege and rapacious wealth, from the outset. A narrator (Richard Boone) introduces the Bel Air setting with the words ‘If you work in the motion picture industry and are successful, this well-tended suburb of Hollywood is where you will probably make your home. Failure is not permitted here’. The narrator adds: ‘Charlie Castle is a man who sold out his dreams; but he can’t forget them’.

Charlie is a compromised protagonist. Early in the film, we are told he was once an idealist who has ‘sold out’ to the Hollywood system, his contract with Hoff-Federated like a pact with the Devil himself. Patty Benedict reminds Charlie of the strong sense of conscience which he has lost, recollecting that Charlie once believed firmly in the New Deal but now thinks only of the Hollywood lifestyle. Charlie once committed himself to scripts and plays that carried a message. This provokes Buddy to respond that ‘Charlie’s motto’ is now ‘“If you got a message, send for Western Union”’. When Marion reminds Charlie of how different he is to the man she married, and suggests he should challenge Hoff and what the producer stands for, Charlie tells her simply that ‘I’m in movie business, darling: I can’t afford your acute attacks of integrity’. ‘What’s happened to your mind, your body, your soul?’, Marion asks her husband, reiterating the notion that his contract with Hoff is like a deal with the very Devil himself, ‘I don’t want one of those witless, sold-out guys sitting around a gin table, swapping phone numbers and the latest dirt [….] You’ve given the studio your pound of flesh’. ‘You were an idealist, Charlie, and you sold out’, Hank tells Castle, ‘There’s nothing more tortured on the face of this earth’. Hank continues, observing that ‘Half idealism, Charlie, is the peritonitis of the soul’.  The film’s opening titles sequence establishes Charlie’s inner turmoil wordlessly: under Frank De Vol’s jazzy music and Saul Bass’ titles, we see an image of Charlie, his head in his hands in a universal gesture of worry and anxiety. The pressures on Charlie continually threaten to bubble into violence, Charlie’s latent aggression handled superbly through Palance’s performance. ‘Play ball with her?’, Charlie asks Buddy when Buddy tells him to be nice to Patty Benedict, ‘I’d like to play ball with her head’. Later, this rage simmers again when Charlie converses with Nat about the contract with Hoff-Federated. ‘Everybody has got a delusion that you’re very tough’, Nat tells Charlie, ‘They mix you up with the parts you play. But I know you better. You’re a special, idealistic type. The only thing is, business and idealism, they don’t mix. It’s oil and water. Movie is not a movie to you: it’s a gospel’. The film’s opening titles sequence establishes Charlie’s inner turmoil wordlessly: under Frank De Vol’s jazzy music and Saul Bass’ titles, we see an image of Charlie, his head in his hands in a universal gesture of worry and anxiety. The pressures on Charlie continually threaten to bubble into violence, Charlie’s latent aggression handled superbly through Palance’s performance. ‘Play ball with her?’, Charlie asks Buddy when Buddy tells him to be nice to Patty Benedict, ‘I’d like to play ball with her head’. Later, this rage simmers again when Charlie converses with Nat about the contract with Hoff-Federated. ‘Everybody has got a delusion that you’re very tough’, Nat tells Charlie, ‘They mix you up with the parts you play. But I know you better. You’re a special, idealistic type. The only thing is, business and idealism, they don’t mix. It’s oil and water. Movie is not a movie to you: it’s a gospel’.

In the years between the first production of the play and Aldrich’s film adaptation, the play’s original star, John Garfield, had suffered a heart attack and passed away in circumstances that strangely parallel the fate of Charlie Castle. Also during those years, some also suggested Odets compromised his own ideals via his ambiguous handling of the questions of the HUAC, and the public response to Odets’ testimony before the HUAC caused much consternation for the writer. Some critics have interpreted Odets’ play as autobiographical. Certainly, it’s perhaps tempting to see the noble Hank, who throughout the film refuses to compromise his ideals (in contrast with Charlie) as a stand-in for Odets himself, Hank’s final monologue offering to speak for the now-absent Hoff player: ‘There will be no photographers’, Hank asserts, ‘No more lies, no display. I’ll tell the story’.

Video

The Big Knife is presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio; the previously available DVDs presented the film open-matte, in the 1.33:1 ratio. 1.85:1 would seem to be the intended ratio: compositions seem to have a far better sense of balance in this presentation than in the film’s previous DVD releases. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The Big Knife is presented in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio; the previously available DVDs presented the film open-matte, in the 1.33:1 ratio. 1.85:1 would seem to be the intended ratio: compositions seem to have a far better sense of balance in this presentation than in the film’s previous DVD releases. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

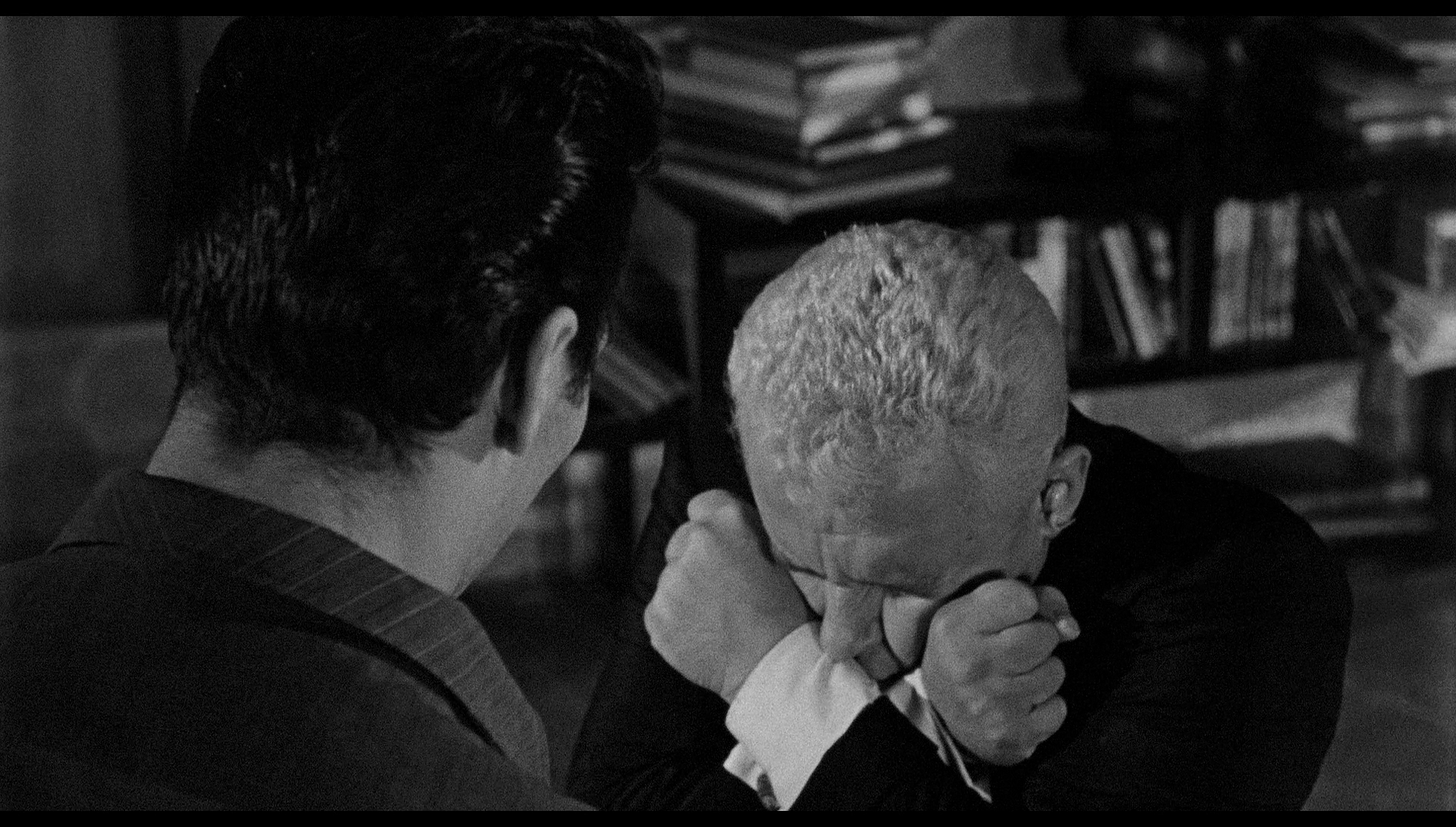

The film was shot in sixteen days by cinematographer Ernest Laszlo, who also photographed Kiss Me Deadly (which was shot in twenty-two days). The decision to shoot the film so quickly, and Laszlo’s careful lighting of shots, meant that the picture had to be shot in long takes staged in depth: ‘You have to sacrifice set-ups’, Aldrich suggested in reference to such condensed production schedules, ‘and hope the performances are good’ (Aldrich, quoted in Silver, op cit.: 59). There’s much staging in depth, characters often appearing in close-up on one side of the screen whilst other characters react to their dialogue in the distance and in the other half of the frame: when working with Joseph Biroc, Aldrich used to call these shots variations of the ‘Rushmore’ (the ‘modified “Rushmore”’, the ‘big “Rushmore”’ and the ‘medium “Rushmore”’) (Aldrich, in ibid.: 60). The film runs for 112:20 minutes and is mostly intact, though in comparison with earlier home video releases this presentation is missing a very small amount of dialogue roughly ninety minutes into the picture: a snippet of a scene, perhaps a minute long, in which Nat and Charlie talk about Hoff. (‘There are things beyond money to that man, but... this much money. You don’t have to worry. He talks with his mouth but he protects his investment’, Nat tells Charlie before offering to take Dixie home and bribe her. ‘No, Nat. It’s too late: it’s too late from my point of view. I can’t go on covering one crime with another: that’s… that’s Macbeth’, Charlie responds, ‘Macbeth is an allegory, Nat: one by one, he kills his better selves’.) The missing dialogue isn’t pivotal but it’s thematically significant.  This issue of missing footage aside, the presentation is excellent. The presentation is billed as a new 2k restoration from ‘original film elements’, though the exact nature of these film elements is unclear. Contrast is very bold, with rich and deep blacks; in conjunction with the defined grain structure of the material, this might suggest that a positive source (or sources) has been used rather than the film’s negative. The level of detail is extremely pleasing throughout, fine detail present in the film’s many close-ups. There is little to no damage present throughout the picture. There are a small handful of shots that appear to be optical zooms/blow-ups – a technique presumably utilised owing to the lack of coverage that was a result of the rushed shooting schedule. These shots are naturally softer, with coarser grain. Contrast levels are very pleasing throughout, deep and rich blacks offset by midtones that have are richly defined. The tonal curves are those of vintage monochrome film stock. (Anyone who’s shot a roll of Tri-X will recognise the character of the monochrome footage on display here.) This issue of missing footage aside, the presentation is excellent. The presentation is billed as a new 2k restoration from ‘original film elements’, though the exact nature of these film elements is unclear. Contrast is very bold, with rich and deep blacks; in conjunction with the defined grain structure of the material, this might suggest that a positive source (or sources) has been used rather than the film’s negative. The level of detail is extremely pleasing throughout, fine detail present in the film’s many close-ups. There is little to no damage present throughout the picture. There are a small handful of shots that appear to be optical zooms/blow-ups – a technique presumably utilised owing to the lack of coverage that was a result of the rushed shooting schedule. These shots are naturally softer, with coarser grain. Contrast levels are very pleasing throughout, deep and rich blacks offset by midtones that have are richly defined. The tonal curves are those of vintage monochrome film stock. (Anyone who’s shot a roll of Tri-X will recognise the character of the monochrome footage on display here.)

Finally, the rich grain structure of the monochrome stock is communicated nicely, resulting in an organic, filmlike experience that is carried through a strong and unproblematic encode to disc.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 2.0 mono track. This is rich and deep, with dialogue that is always audible. The audio track is in a little worse shape than the photographic materials used for this release, and features noticeable hum, pop and crackle throughout a handful of scenes; this never buries the dialogue and sound design but is present nonetheless. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are provided. These are easy to read and free from errors, accurate in their documentation of the film’s dialogue.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with critics Glenn Kenny and Nick Pinkerton. The pair spend some time attempting to categorise the picture as a film noir or not a film noir, which is perhaps a non-question – especially with a filmmaker such as Aldrich, whose pictures frequently defy easy classification. This aside, it’s an excellent track, and Kenny and Pinkerton evidence their considerable appreciation of cinema history, exploring the film’s depiction of Hollywood, its origins in Odets’ stage play and its relationship with Aldrich’s other pictures. It’s a highly commendable commentary track, and fans of Aldrich or simply those interested in the history of classical Hollywood cinema will find much to enjoy here. - Bass on Titles (33:46). An archival documentary from 1977, made by Saul Bass himself, explores Bass’ work as a designer of film titles. Bass is articulate about his methods, and explores his work on some of the films for which he is known. - TV promotional piece (4:59). This is one of those short ‘visit to the set’ pieces that were popular during the 1950s; intended for broadcast on American television, it shows the cast and crew during the shooting of the picture. - Trailer (2:28).

Overall

The play, and this film, is rich in dialogue, featuring some sparkling exchanges that equal those in the later Odets-scripted picture Sweet Smell of Success (Alexander Mackendrick, 1957). The Big Knife confronts the nature of Hollywood cinema, exploring directly the tension between cinema as an art form and cinema as an ‘industry’; into the dialogue are dropped names of real film directors (Marion reels off a list of ‘worthy’ directors that includes Billy Wilder and Elia Kazan, among others), and at times the picture becomes deliriously metafictional. (‘You’re so lucky. If this were a movie’, Charlie threatens Hoff towards the climax, ‘you would have been on the floor ten times’.) In Hoff, a number of recognisable traits of Hollywood gurus are present – in particular, Louis B Mayer’s tendency to use tears to get his way. There are also some overt allusions to Faust (‘If you’re in trouble, if there’s anything Old Nick can do…’, Charlie’s personal trainer declares at one point). The play, and this film, is rich in dialogue, featuring some sparkling exchanges that equal those in the later Odets-scripted picture Sweet Smell of Success (Alexander Mackendrick, 1957). The Big Knife confronts the nature of Hollywood cinema, exploring directly the tension between cinema as an art form and cinema as an ‘industry’; into the dialogue are dropped names of real film directors (Marion reels off a list of ‘worthy’ directors that includes Billy Wilder and Elia Kazan, among others), and at times the picture becomes deliriously metafictional. (‘You’re so lucky. If this were a movie’, Charlie threatens Hoff towards the climax, ‘you would have been on the floor ten times’.) In Hoff, a number of recognisable traits of Hollywood gurus are present – in particular, Louis B Mayer’s tendency to use tears to get his way. There are also some overt allusions to Faust (‘If you’re in trouble, if there’s anything Old Nick can do…’, Charlie’s personal trainer declares at one point).

Arrow’s new presentation of the film is, a snippet of missing dialogue aside, excellent: Laszlo’s photography is represented beautifully here, thanks in particular to the use of the film’s intended 1.85:1 aspect ratio. The audio track has some damage present in a number of scenes, but nothing that is too distracting. The missing footage is frustrating as in all other aspects, the presentation of the main feature is utterly superb – remedying the relative neglect the picture has suffered on digital home video, especially in comparison with its near-neighbour Kiss Me Deadly. The contextual material is very good, the commentary with Kenny and Pinkerton offering a strong contextualisation of the film’s themes in particular. Possibly like many film fans of a similar age to myself, my first exposure to this picture (and a number of Aldrich’s films, including Ulzana’s Raid and Kiss Me Deadly) was via its broadcast on BBC2’s Moviedrome in the early 1990s. The film lingered in my memory though remained fairly difficult to see. This new Blu-ray release is a revelation, almost like seeing the film for the first time once again. If there’s a way for Arrow to remedy the brief moment of missing footage, this release of The Big Knife would be definitive; in all other respects, it’s certainly the release that this undersung film deserves. References: Silver, Alain, 1970: ‘Interview with Robert Aldrich’. In: Miller, Eugene L & Arnold, Edwin T (eds), 2004: Robert Aldrich: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 53-72

|

|||||

|