|

|

Ronin (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (24th August 2017). |

|

The Film

Ronin (John Frankenheimer, 1998) Ronin (John Frankenheimer, 1998)

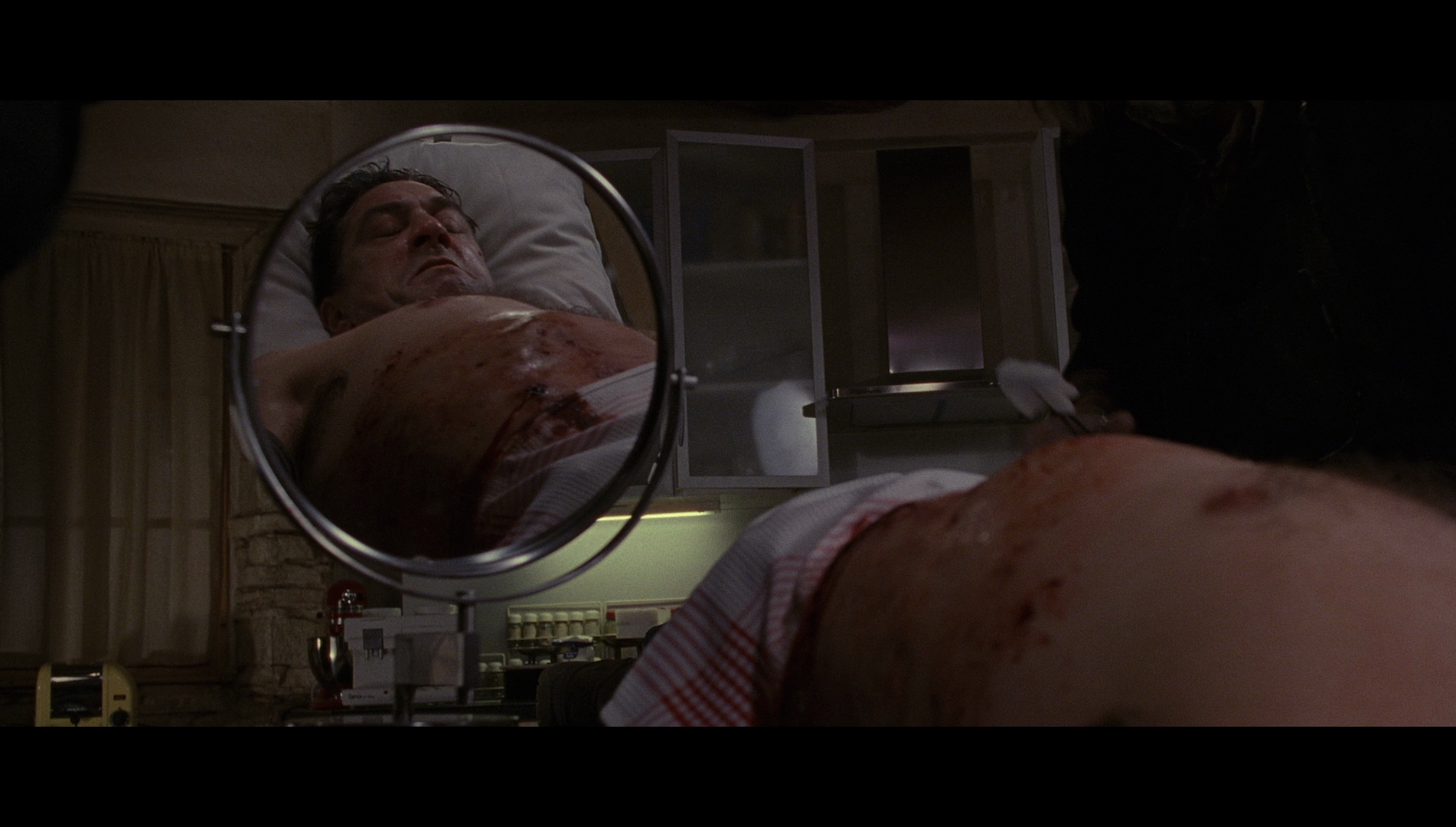

In Paris, a group of ‘specialists’ are gathered together by Deirdre (Natascha McElhone); former members of various military and security agencies, these specialists are tasked with ambushing a vehicle and acquiring a metal briefcase that is due to be handed over to the Russians in Nice. Amongst the men hired by Deirdre are ex-CIA agent Sam (Robert De Niro), ‘fixer’ Vincent (Jean Reno), electronics expert Gregor (Stellan Skarsgaard), wheelman Karry (Skipp Sudduth) and Spence (Sean Bean), who claims to be a veteran of the SAS. Unbeknownst to the men she has hired, Deirdre takes her orders from IRA agent O’Rourke (Jonathan Pryce). Sam and Vincent quickly become friends, their mutual respect escalating when an arms deal on the bank of the Seine goes wrong – and Spence proves himself to be a worthless blowhard. Returning to the warehouse that Deirdre’s crew have made their temporary headquarters, Sam humiliates Spence in front of the others, proving that Spence’s claim to be a former member of the SAS was a lie. Spence leaves the group. However, together with Vincent, Sam begins to wonder who Deirdre’s employers are. In Nice, the group plan the ambush and execute it, seizing the briefcase. However, they are double-crossed by Gregor, who exploits the situation to take control of the briefcase. (‘Gregor fucked us’, Sam observes tersely.) As Gregor tries to sell the briefcase to the highest bidder, proving himself to be a ruthless killer into the bargain, Sam and the others attempt to track Gregor’s movements, leading them into direct confrontation with the KGB and the Russian mob. When Sam and the others enable Deidre to capture Gregor, they are betrayed. Sam is shot in the stomach and, together with O’Rourke, Deirdre takes the briefcase.  Vincent takes Sam to an acquaintance, a veterinarian named Jean-Pierre (Michael Lonsdale) who spends his spare time assembling an intricate diorama depicting the exploits of the forty-seven ronin. Sam directs Jean-Pierre in removing the gun from his own stomach. As Sam recovers, Jean-Pierre explains to Sam the concept of ronin: masterless samurai shamed by the death of their master and who live by the ‘warrior code’. Vincent takes Sam to an acquaintance, a veterinarian named Jean-Pierre (Michael Lonsdale) who spends his spare time assembling an intricate diorama depicting the exploits of the forty-seven ronin. Sam directs Jean-Pierre in removing the gun from his own stomach. As Sam recovers, Jean-Pierre explains to Sam the concept of ronin: masterless samurai shamed by the death of their master and who live by the ‘warrior code’.

The film takes place in the years after the Cold War, and is filled with a similarly weary and cynical approach to international relations as Martin Campbell’s roughly contemporaneous James Bond picture Goldeneye (1995). In Ronin, an ex-CIA member is pitted alongside a multinational crew of mercenaries against the IRA, the KGB and the Russian mob. The contents of the case that Sam, Vincent and the others are hired to seize are ambiguous – like the contents of the briefcase in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction (1994) of a few years earlier – and the object functions as a classic ‘MacGuffin’. The French setting and references to the code of the samurai invite comparisons between Ronin and Jean-Pierre Melville’s referential polars of the 1960s and early 1970s – in particular, Le Samouraï (1967), Le cercle rouge (1970) and Un flic (1972). (A year later, Jim Jarmusch’s Ghost Dog: Way of the Samurai would feature a similar exploration of the relationship between the code of samurai and the underworld, though Jarmusch’s film is set in America.) Ronin begins with a series of titles explaining that ‘ronin’ were masterless samurai; these titles are arguably redundant, especially considering that later in the film Jean-Pierre explains the concept of ‘ronin’ to Sam whilst Sam is recovering from a gunshot wound in Jean-Pierre’s home. This discussion takes place within the context of Sam’s questions about the diorama Jean-Pierre is assembling: the diorama is of the forty-seven ronin, Jean-Pierre tells Sam, ‘Forty-seven samurai whose master was betrayed and killed by another lord. They became ronin – masterless samurai – disgraced by another man’s treachery. For three years they plotted, pretending to be thieves, mercenaries, even madmen [...] And then one night they struck, slipping into the castle of their lord’s betrayer, killing him [….] You understand it [….] The warrior code, the delight in the battle. You understand that, yes? But also something more. You understand there is something outside yourself that has to be served. And when that need has gone, when that belief has died, what are you? A man without a master [….] The ronin could have hired themselves to new masters. They could have fought for themselves. But they chose honour, they chose myth’. The masterless samurai in the film, it seems, are all former members of various groups made redundant when the Cold War ended – the CIA, KGB and SAS. This is a key theme of the film, but one which remains largely unspoken within David Mamet’s typically sparse script, which unlike many Hollywood action films says more through action, behaviour and indirect speech than via traditional expository dialogue.  Via subtle gestures, in the opening sequence Sam is established as extremely cautious and careful in his planning. (One might recall CIA man George Hansen/Robert Duvall’s line in Sam Peckinpah’s The Killer Elite, 1975: ‘Always operate on the six “P” principle: Proper Planning Prevents Piss-Poor Performance’.) Before entering the Parisian pub in which he is scheduled to meet Deirdre, Vincent and the others, Sam watches the location from a distance, hiding in the shadows to spy on Deirdre as she enters the pub. It’s a slow-burning, suspenseful scene that plays out through close-ups of Sam’s face and staging in depth behind him; in this sense, structurally and photographically the scene recalls the distinctive opening scenes of Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Sam goes to the back door and places two pistols in a bucket, in preparation for a swift escape: his actions here might deliberately reference Mark’s (Chow Yun-Fat) near-identical preparatory gesture before ambushing the leader of the rival Taiwanese gang in John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow (1986). Following his entry into the pub and introductions to Deirdre and Vincent, Sam feels safe leaving with his new temporary colleagues, and on his way out the pub Sam collects the two pistols he placed by the rear entrance. ‘I never walk into a place I don’t know how to get out of’, he tells Deirdre by way of explanation. Later, in Nice, Sam surveys the maps but tells Deirdre that ‘The map is not the territory’ (in a possible nod to Borges, or perhaps Baudrillard): he needs to look at ‘the ground’ and comes up with an elaborate plan to get as close a look at the quarry as possible. Sam is also a realist. When blowhard Spence talks about interrogation and holding out under questioning, Sam tells him ‘Nobody can hold out indefinitely [….] Everybody has a limit’. In Nice, when asked by Deirdre ‘Are you afraid?’, Sam answers honestly: ‘Of course I’m afraid. You think I’m reluctant because I’m happy?’ Via subtle gestures, in the opening sequence Sam is established as extremely cautious and careful in his planning. (One might recall CIA man George Hansen/Robert Duvall’s line in Sam Peckinpah’s The Killer Elite, 1975: ‘Always operate on the six “P” principle: Proper Planning Prevents Piss-Poor Performance’.) Before entering the Parisian pub in which he is scheduled to meet Deirdre, Vincent and the others, Sam watches the location from a distance, hiding in the shadows to spy on Deirdre as she enters the pub. It’s a slow-burning, suspenseful scene that plays out through close-ups of Sam’s face and staging in depth behind him; in this sense, structurally and photographically the scene recalls the distinctive opening scenes of Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). Sam goes to the back door and places two pistols in a bucket, in preparation for a swift escape: his actions here might deliberately reference Mark’s (Chow Yun-Fat) near-identical preparatory gesture before ambushing the leader of the rival Taiwanese gang in John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow (1986). Following his entry into the pub and introductions to Deirdre and Vincent, Sam feels safe leaving with his new temporary colleagues, and on his way out the pub Sam collects the two pistols he placed by the rear entrance. ‘I never walk into a place I don’t know how to get out of’, he tells Deirdre by way of explanation. Later, in Nice, Sam surveys the maps but tells Deirdre that ‘The map is not the territory’ (in a possible nod to Borges, or perhaps Baudrillard): he needs to look at ‘the ground’ and comes up with an elaborate plan to get as close a look at the quarry as possible. Sam is also a realist. When blowhard Spence talks about interrogation and holding out under questioning, Sam tells him ‘Nobody can hold out indefinitely [….] Everybody has a limit’. In Nice, when asked by Deirdre ‘Are you afraid?’, Sam answers honestly: ‘Of course I’m afraid. You think I’m reluctant because I’m happy?’

The alliances within Deidre’s group are fragile. (‘Everyone’s your brother until the rent comes due’, Vincent tells Sam at one point, to which Sam responds in agreement: ‘Ain’t that the truth!’) Spence’s claim to be a veteran of the SAS is highly dubious, as Sam proves during a confrontation with Spence. During a weapons-purchasing mission gone wrong, when Spence proves himself to be both a blowhard and a bag of nerves (vomiting after a memorable firefight that takes place on the banks of the Seine), Sam demands that Spence tell him ‘What’s the colour of the boathouse at [the SAS training camp at] Hereford?’ Spence can’t answer Sam, and this is taken as evidence that Spence has been deceiving the others about his background. After Spence leaves, Vincent asks Sam what colour the boathouse is; Sam responds by telling the others he has no idea whether or not there is a boathouse at Hereford – it was simply a ruse to smoke out Spence’s lies. With this, Spence is quickly marked as someone who doesn’t belong with the elite group that Deirdre has assembled in service of O’Rourke’s demands. The alliances within Deidre’s group are fragile. (‘Everyone’s your brother until the rent comes due’, Vincent tells Sam at one point, to which Sam responds in agreement: ‘Ain’t that the truth!’) Spence’s claim to be a veteran of the SAS is highly dubious, as Sam proves during a confrontation with Spence. During a weapons-purchasing mission gone wrong, when Spence proves himself to be both a blowhard and a bag of nerves (vomiting after a memorable firefight that takes place on the banks of the Seine), Sam demands that Spence tell him ‘What’s the colour of the boathouse at [the SAS training camp at] Hereford?’ Spence can’t answer Sam, and this is taken as evidence that Spence has been deceiving the others about his background. After Spence leaves, Vincent asks Sam what colour the boathouse is; Sam responds by telling the others he has no idea whether or not there is a boathouse at Hereford – it was simply a ruse to smoke out Spence’s lies. With this, Spence is quickly marked as someone who doesn’t belong with the elite group that Deirdre has assembled in service of O’Rourke’s demands.

Though John Frankenheimer had established himself as something of an auteur during the 1960s with his distinctive work on pictures such as The Train (1964) and Seconds (1966), during the later years of his career critics tended to focus on his less impressive pictures (for example, 1982’s The Challenge and 1996’s The Island of Dr Moreau) whilst often overlooking some of the outstanding films Frankenheimer made during the 1980s and 1990s (including 52 Pick-Up in 1986, recently released by Arrow on Blu-ray and reviewed by us here). Nevertheless, at the time of its initial release Ronin (1998) was praised by many as a return to the lean, muscular and meaningful action filmmaking with which Frankenheimer had been associated during his early career as a feature film director.  Ronin has a story that in many hands would seem a conventional post-Cold War thriller, but Frankenheimer’s direction – and celebrated playwright David Mamet’s trademark lean dialogue; Mamet doctored the script in an uncredited role – gives the narrative an abstracted, symbolic quality. (A legal battle followed the film’s release over Mamet’s role in the script, with J D Zeik, who wrote the original outline, claiming that he wrote the bulk of the dialogue; this was against the claims of Frankenheimer, who argued that the dialogue was predominantly Mamet’s.) Within the film, character is established via terse exchanges of dialogue in which motivation is communicated through subtext and via periphrasis. Frankenheimer directs the scenes of dialogue with the same import as his handling of Eugene O’Neill’s play The Iceman Cometh in 1973. The various celebrated scenes of action – several high-octane car chases and an ambush in narrow streets that features naturalistic gunplay similar to that in Michael Mann’s Heat (1996), in which Andy McNab gave the actors (including Ronin’s Robert De Niro) weapons training – are impactful, but pared down to its essentials Ronin is formal and symbolic – like an absurdist play welded to the spectacle of an action film. Ronin has a story that in many hands would seem a conventional post-Cold War thriller, but Frankenheimer’s direction – and celebrated playwright David Mamet’s trademark lean dialogue; Mamet doctored the script in an uncredited role – gives the narrative an abstracted, symbolic quality. (A legal battle followed the film’s release over Mamet’s role in the script, with J D Zeik, who wrote the original outline, claiming that he wrote the bulk of the dialogue; this was against the claims of Frankenheimer, who argued that the dialogue was predominantly Mamet’s.) Within the film, character is established via terse exchanges of dialogue in which motivation is communicated through subtext and via periphrasis. Frankenheimer directs the scenes of dialogue with the same import as his handling of Eugene O’Neill’s play The Iceman Cometh in 1973. The various celebrated scenes of action – several high-octane car chases and an ambush in narrow streets that features naturalistic gunplay similar to that in Michael Mann’s Heat (1996), in which Andy McNab gave the actors (including Ronin’s Robert De Niro) weapons training – are impactful, but pared down to its essentials Ronin is formal and symbolic – like an absurdist play welded to the spectacle of an action film.

Video

This presentation of Ronin takes up a little over 36Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. This presentation of Ronin takes up a little over 36Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

The film is uncut, with a running time of 121:34 mins. The staging within the colour 35mm widescreen photography (the film was shot in the Super 35 process with the intention of being exhibited at 2.40:1, the ratio in which it is presented on this Blu-ray release) resembles that in Frankenheimer’s 1960s films, including The Manchurian Candidate: faces loom in the foreground of the frame, whilst action takes place in the background. This staging-in-depth, largely achieved via the use of short focal lengths and sometimes achieved via split-dioptre lenses too (predominantly in low-light scenes and interiors), is articulated very well in this presentation, the impressive level of fine detail contributing a strong sense of depth to the imagery within the film. Frankenheimer was said to have chosen to shoot the film in Super 35, rather than anamorphically, because of the increased depth of field afforded by the process and its use of spherical lenses (see Prince, 2011: 85). Contrast levels are very pleasing, with midtones having a strong sense of definition and shadows soft but defined. Colours are represented naturalistically. There is no damage to speak of, and the encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

The viewer is given the option of watching the film with a DTS-HD MA 5.1 track or a LPCM 2.0 stereo track. The former has added ‘oomph’, especially during the action scenes, the sound separation creating a strong sense of depth to the soundscape. The latter has a more consistent sense of depth to it, however. Both tracks are clean and dialogue is easy to hear throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are easy to read, accurate in transcribing the dialogue and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with Frankenheimer. This is the same commentary track that has appeared on Ronin’s previous DVD releases, with Frankenheimer talking at length about some of the techniques employed in the production. It’s a detailed, informative track, Frankenheimer’s wealth of experience being evident throughout. - ‘Close-Up’ (31:27). Robert Fraisse, who acted as cinematographer on Ronin, discusses his career and methods before talking about the photography in Frankenheimer’s film – mostly achieved via the use of lenses below 35mm in focal length. Fraisse also reflects on some of the techniques used to photograph the car chases. - ‘You Talkin’ to Me?’ (27:01). From 1994, this episode of Channel 4’s series Cinefile was directed by Paul Joyce and sees Quentin Tarantino talking about De Niro’s career as an actor. This was originally broadcast on Channel 4 at the front-end of a season of films starring De Niro (which began with The Deer Hunter and also included Mean Streets, The Godfather Part II, Once Upon a Time in America, Taxi Driver, Mean Streets and Raging Bull). I remember this very vividly from its original broadcast, Tarantino’s enthusiasm for De Niro’s work as a performer being infectious (and predating Tarantino’s casting of De Niro in his 1997 film Jackie Brown). The following featurettes and interviews, which have previously been seen on the film’s various DVD releases, are also included: - ‘Ronin: Filming in the Fast Lane’ (17:45). This EPK featurette include video-shot footage from the set and interviews with the principals. - ‘Through the Lens’ (17:57). Another EPK featurette focuses on Fraisse’s photography for the film, and again balances interviews with on-set footage. - ‘The Driving of Ronin’ (15:29). The driving during the car chase sequences is examined, with a discussion of the logistics involved in achieving such moments. (In French, with burnt-in English subtitles.) - ‘Natascha McElhone: An Actor’s Process’ (13:57). This piece examines Natascha McElhone’s work as an actor and her responses to Frankenheimer’s direction – and working with the other actors. - ‘Composing the Ronin Score’ (11:52). Elia Cmiral talks about the process of composing the music for the film. - ‘In the Cutting Room’ (18:56). This featurette focuses on the cutting of the film. - Venice Film Festival Interviews (20:41). Various interviews with the cast and crew, shot during the junket at the Venice Film Festival in 1998, are presented here. - Alternate Ending (1:49). Adding some footage to the closing scene as seen in the finished film, this alternate ending would have left the audience with a very different set of emotions. - Trailer (2:28). - Stills Gallery (0:37).

Overall

An excellent thriller, at the time of its initial release Ronin provided an antidote to the big, flashy action pictures of the 1990s (exemplified by the likes of Michael Bay’s The Rock, 1996, and Simon West’s Con Air, 1997). The dialogue is pared down and existential, filled with subtext and subtle ambiguities. Frankenheimer’s handling of the action – not just the lauded car chases, often cited as throwbacks to the car chases in 1970s pictures such as William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971) and Philip D’Antoni’s The Seven-Ups (1973) – is as masterful and confident as one would expect from a filmmaker with Frankenheimer’s many years of experience. Though some of the films Frankenheimer made in the 1980s and 1990s were less impressive than his work throughout the 1960s, a handful of the pictures directed by Frankenheimer during the latter years of his career were exemplary; Ronin is one of those films. An excellent thriller, at the time of its initial release Ronin provided an antidote to the big, flashy action pictures of the 1990s (exemplified by the likes of Michael Bay’s The Rock, 1996, and Simon West’s Con Air, 1997). The dialogue is pared down and existential, filled with subtext and subtle ambiguities. Frankenheimer’s handling of the action – not just the lauded car chases, often cited as throwbacks to the car chases in 1970s pictures such as William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971) and Philip D’Antoni’s The Seven-Ups (1973) – is as masterful and confident as one would expect from a filmmaker with Frankenheimer’s many years of experience. Though some of the films Frankenheimer made in the 1980s and 1990s were less impressive than his work throughout the 1960s, a handful of the pictures directed by Frankenheimer during the latter years of his career were exemplary; Ronin is one of those films.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of Ronin contains an excellent presentation of the main feature that is accompanied by a superb array of contextual material, both old and new. In particular, it’s a delight to see Paul Joyce and Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 piece about De Niro again. This is a commendable release that should be very pleasing for fans of the film or of Frankenheimer’s work. References: Prince, Stephen, 2011: ‘Action and Abstraction in Ronin’. In: Pomerance, Murray & Palmer, R Barton (eds), 2011: A Little Solitaire: John Frankenheimer and American Film. Rutgers University Press: 78-90

|

|||||

|