|

|

The Film

Madhouse AKA There Was a Little Girl (Ovidio G Assonitis, 1981) Madhouse AKA There Was a Little Girl (Ovidio G Assonitis, 1981)

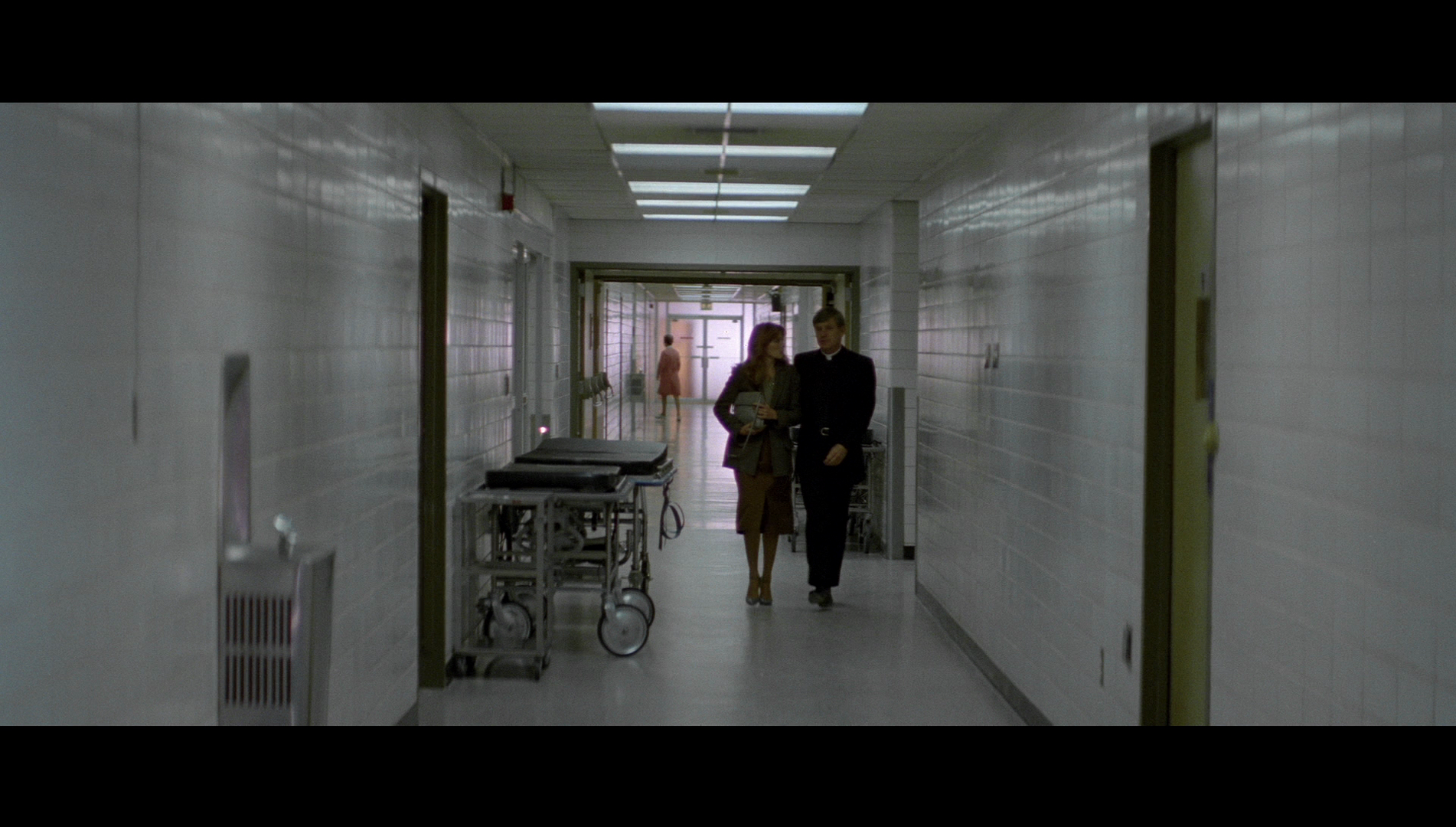

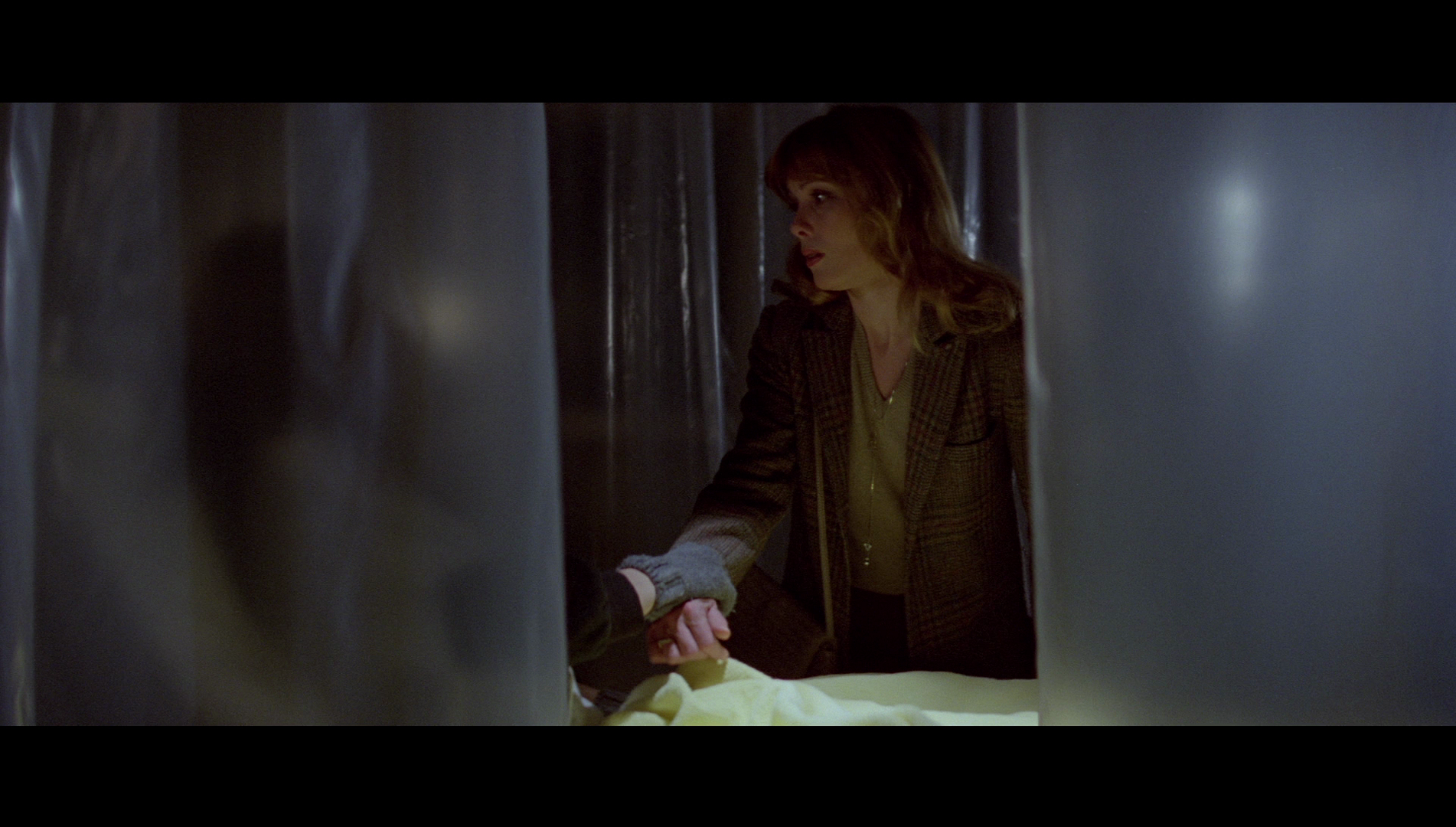

An American-set film by the Egyptian-born director Ovidio G Assonitis, a filmmaker most commonly associated with Americanised Italian genre cinema (the San Francisco-set Chi sei?/Beyond the Door, 1974; the California-set Tentacoli/Tentacles, 1977), Madhouse conforms roughly to the paradigms of the American stalk-and-slash/bodycount/slasher pictures of the era. Though shot in America, Madhouse was made by an almost all-Italian crew and the film seems to have an askance outsider’s view of American culture – rather like some of the American-set Italian thrillers and horror films of the early 1980s. With its setting in Georgia, Madhouse might suggest – like Lucio Fulci’s L’adilà (The Beyond, 1981), which has a similar setting in the southern states of the US – a fascination by international, and specifically Italian, filmmakers with the Gothic and its importance in the South. (Interestingly, the film was shot in the Kehoe house in Savannah, Georgia, a hotel which is rumoured to be haunted by several ghosts, including a woman who can be heard sobbing hysterically on the top floor of the building.) Madhouse focuses on Julia Sullivan (Trish Everly), a teacher at a school for deaf children; the story begins five days before Julia’s birthday. She is approached by her Uncle James (Dennis Robertson), a priest, who insists that Julia visits her mentally disturbed twin sister Mary (Allison Biggers) in the hospital. Remembering the years of cruelty that she suffered at the hands of Mary, who would torment Julia with her dog before hurting her spitefully, Julia is initially reluctant but finally agrees to the visit. However, James warns Julia that a virus has deformed Mary’s features to such an extent that Mary may not be able to recognise her twin. However, whilst Julia is alone with Mary, Mary springs suddenly from her bed to grab Julia’s arm, threatening to make Julia suffer.  Julia attempts to confide in James, telling him how cruel Mary was to her when they were children. However, James doesn’t believe Julia’s stories. Instead, Julia tells her lover Sam Edwards (Michael MacRae), a psychiatrist: ‘When we were children, we were identical in every way’, she says, ‘But she was a mistress and I was her slave’. Julia attempts to confide in James, telling him how cruel Mary was to her when they were children. However, James doesn’t believe Julia’s stories. Instead, Julia tells her lover Sam Edwards (Michael MacRae), a psychiatrist: ‘When we were children, we were identical in every way’, she says, ‘But she was a mistress and I was her slave’.

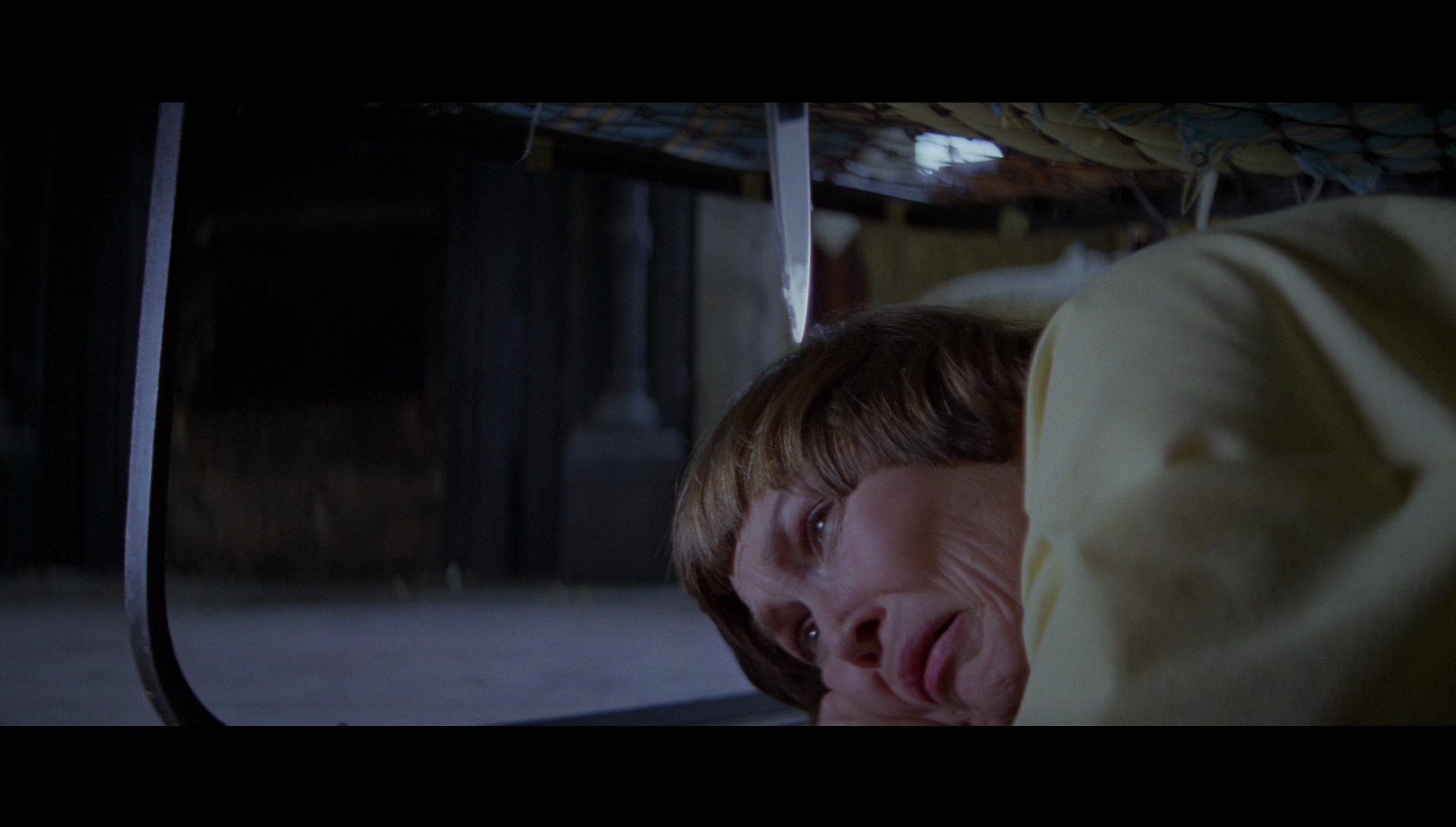

Julia returns to her apartment and is startled in the basement by Mr Kimura (Jerry Fujikawa), the superintendent of the building, who has been tasked by eccentric landlady Amantha Bureaugard (Edith Ivey) with renovating the top floor apartment. Meanwhile, one of the security guards at the hospital is killed by a dog, the guard’s throat torn out. The next day, whilst at work Julia is informed that Mary has escaped from the hospital. While Julia is away, Mr Kimura is killed by the same dog that attacked the hospital security guard. The dog is Mary’s; Mary hides in the empty apartment. Mary soon claims another victim: Julia’s favourite pupil, a young deaf boy named Sacha (Richard Baker). Julia suggests to James and Sam that Mary may be responsible for Sacha’s death. James denies this vehemently, suggesting Julia is delusional. Sam, however, is more open to suggestion and asks Julia’s friend Helen (Morgan Hart) to spend the night with Julia in her apartment.  During the night, Helen is lured out of Julia’s apartment to the rooms upstairs, where she is killed by Mary’s dog. The next day, Sam and Julia reflect on Helen’s disappearance, but Sam insists he must journey to San Francisco to deliver a speech. Meanwhile, back at the house Amantha is asked by James to help him prepare a birthday surprise for Julia. Amantha assists James in carrying a heavy wrapped object into the basement of the building. Once inside the building, however, Amantha discovers that the object is the corpse of the hospital security guard, which has been wrapped in plastic. With this revelation, James turns on the landlady and pursues her through the building before killing her in the empty upstairs apartment. It only remains for Julia to discover the true nature of the birthday surprise prepared for her by her sister and uncle. During the night, Helen is lured out of Julia’s apartment to the rooms upstairs, where she is killed by Mary’s dog. The next day, Sam and Julia reflect on Helen’s disappearance, but Sam insists he must journey to San Francisco to deliver a speech. Meanwhile, back at the house Amantha is asked by James to help him prepare a birthday surprise for Julia. Amantha assists James in carrying a heavy wrapped object into the basement of the building. Once inside the building, however, Amantha discovers that the object is the corpse of the hospital security guard, which has been wrapped in plastic. With this revelation, James turns on the landlady and pursues her through the building before killing her in the empty upstairs apartment. It only remains for Julia to discover the true nature of the birthday surprise prepared for her by her sister and uncle.

Assonitis’ previous Italian films had demonstrated a slavish commitment to the principle of the filone, following the stream of what was popular at the time: Chi sei? had been heavily influenced by the success of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), and Tentacoli was one of a wave of nature-gone-amok films that capitalised on the success of Jaws. Madhouse follows the conventions of popular slasher films very closely, taking its focus on the family and fratricide from John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), featuring some of the good/bad sister interplay of Brian De Palma’s Sisters (1973), and featuring a macabre birthday party climax that is strikingly similar to that of J Lee Thompson’s Happy Birthday to Me (released the same year, 1981). Assonitis’ film was originally known as There Was a Little Girl, in reference to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem, quoted in the film by James: ‘There was a little girl / Who had a little curl / Right in the middle of her forehead / When she was good / She was very, very good / But when she was bad she was horrid’.  Much has been said about Lucio Fulci’s Quella villa accanto al cimitero (The House by the Cemetery), released the same year as Madhouse, and the manner in which the film strives for literary significance via the presentation of a quote (‘No one will ever know whether children are monsters, or monsters are children’) attributed to Henry James during the film’s closing credits. Though this quote may strike the casual observer as fitting in relation to some of the themes explored in James’ 1898 novella The Turn of the Screw, in particular, those words were never written by James. Likewise, Madhouse reaches for similar literary significance in its use during the closing credits of a quote attributed to ‘G B Shaw’ – presumably George Bernard Shaw. (Strikingly, the onscreen font used in Madhouse is extremely similar to the font used for the onscreen titles in The House by the Cemetery.) The quote in Madhouse is indeed a genuine quote rather than a fabrication – but it’s misattributed to Shaw. The words (‘Life differs from the play in this… it has no plot, all is vague, desultory, unconnected till the curtain drops with the mystery unsolved’) were instead written by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, in his 1842 novel Godolphin. Much has been said about Lucio Fulci’s Quella villa accanto al cimitero (The House by the Cemetery), released the same year as Madhouse, and the manner in which the film strives for literary significance via the presentation of a quote (‘No one will ever know whether children are monsters, or monsters are children’) attributed to Henry James during the film’s closing credits. Though this quote may strike the casual observer as fitting in relation to some of the themes explored in James’ 1898 novella The Turn of the Screw, in particular, those words were never written by James. Likewise, Madhouse reaches for similar literary significance in its use during the closing credits of a quote attributed to ‘G B Shaw’ – presumably George Bernard Shaw. (Strikingly, the onscreen font used in Madhouse is extremely similar to the font used for the onscreen titles in The House by the Cemetery.) The quote in Madhouse is indeed a genuine quote rather than a fabrication – but it’s misattributed to Shaw. The words (‘Life differs from the play in this… it has no plot, all is vague, desultory, unconnected till the curtain drops with the mystery unsolved’) were instead written by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, in his 1842 novel Godolphin.

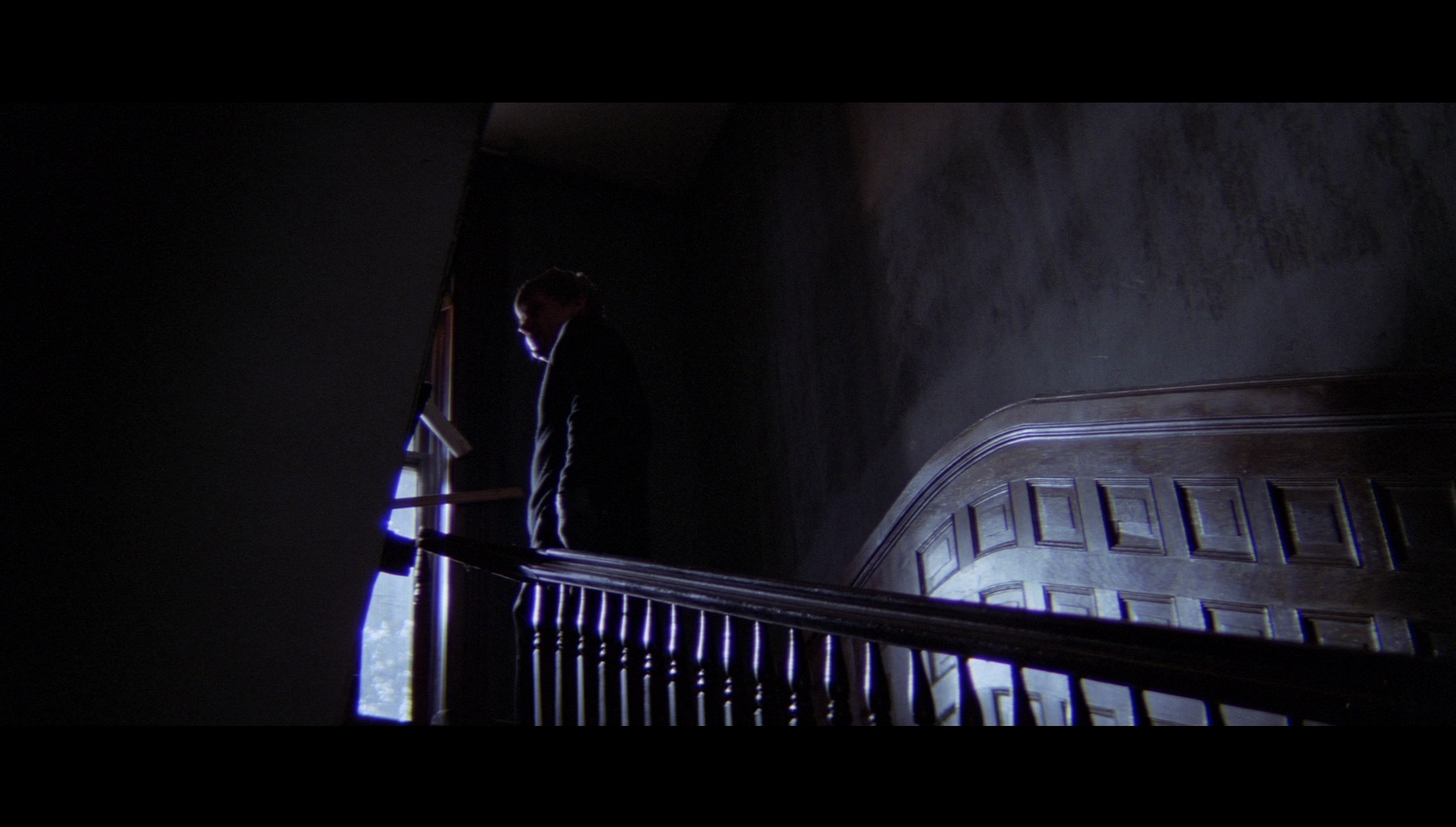

Like a number of films of the era (for example, Joe D’Amato’s Absurd, 1980), during its initial appearance on home video in the UK, in the years prior to the Video Recordings Act, Madhouse was reputedly released on video by its distributor (Medusa) in both cut and uncut versions. Famously, however, like the aforementioned Fulci films, Madhouse found itself on the DPP’s list of official ‘video nasties’ – films that were considered prosecutable under the terms outlined in the Obscene Publications Act. However, there’s little within Madhouse to ‘deprave or corrupt’ its audience. The most graphic moments come when Mary’s dog attacks those around Julia, ripping out their throats in a similar manner to which Dickie the guide dog tears out the throat of Emily (Cinzia Monreale) in The Beyond or the blind piano player’s dog tears out the throat of its master (Flavio Bucci) in Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977). The dog itself is dispatched quite vividly, when Sam buries a power drill into its skull (or rather, the skull of a particularly unconvincing puppet).  Given its reputation as a ‘video nasty’, Madhouse is strikingly restrained, relying more upon atmosphere than gore. Assonitis uses low-angle shots taken with wide-angle lenses to make the interior of the Kehoe house seem strange and threatening, characters appearing in frames-within-frames. The film’s moments of terror take place within the domestic space: the Kehoe house, in which Mary hides after killing the supervisor Mr Kimura and, later, Mary’s landlady Amantha. Mary conceals herself in the empty apartment above Julia’s, her presence suggested via whispers and mocking laughter. (Prior to her death, Helen hears Mary whispering her name, calling her out of Julia’s apartment and into danger.) In this sense, Mary is like a ghost shorn of its corporeal form, only appearing as a physical entity a handful of times within the film. (In this context, one may wonder whether the production was influenced by the fact that the top floor of the Kehoe house is said to be haunted by the ghost of woman who sobs but who never manifests herself physically.) In its depiction of Julia’s ‘haunting’ by Mary, James’ obsession with the ‘absent’ Mary, and the suggestion that Mary and James may be trying to ‘gaslight’ Julia, the film has some similarities with Daphne Du Maurier’s 1938 novel Rebecca; other than its setting in Georgia, Madhouse’s plot feels extraordinarily like that of a Gothic novel of the late 19th or early 20th Centuries. Given its reputation as a ‘video nasty’, Madhouse is strikingly restrained, relying more upon atmosphere than gore. Assonitis uses low-angle shots taken with wide-angle lenses to make the interior of the Kehoe house seem strange and threatening, characters appearing in frames-within-frames. The film’s moments of terror take place within the domestic space: the Kehoe house, in which Mary hides after killing the supervisor Mr Kimura and, later, Mary’s landlady Amantha. Mary conceals herself in the empty apartment above Julia’s, her presence suggested via whispers and mocking laughter. (Prior to her death, Helen hears Mary whispering her name, calling her out of Julia’s apartment and into danger.) In this sense, Mary is like a ghost shorn of its corporeal form, only appearing as a physical entity a handful of times within the film. (In this context, one may wonder whether the production was influenced by the fact that the top floor of the Kehoe house is said to be haunted by the ghost of woman who sobs but who never manifests herself physically.) In its depiction of Julia’s ‘haunting’ by Mary, James’ obsession with the ‘absent’ Mary, and the suggestion that Mary and James may be trying to ‘gaslight’ Julia, the film has some similarities with Daphne Du Maurier’s 1938 novel Rebecca; other than its setting in Georgia, Madhouse’s plot feels extraordinarily like that of a Gothic novel of the late 19th or early 20th Centuries.

Residing in the apartment at the top of the Kehoe building, which is under renovation by Mr Kimura and is therefore empty, Mary becomes the film’s ‘mad woman in the attic’ – a key archetype within Gothic fiction. Allison Biggers invests Mary’s voice with a shrill, constantly near-hysterical pitch: ‘Remember how we used to celebrate, sister dear?’, Mary asks Julia when Julia visits her in the hospital, ‘Remember how you’d hide from me, but I’d find you anyway? Remember what I’d do, how it’d hurt? Well, I will make it hurt again! I will make you suffer like I’ve suffered you!’ For much of the film’s running time, it seems that the antagonist(s) are seeking to drive Julia insane. From the start, Julia suggests a curious bond between herself and Mary, which James and Mary attempt to exploit: ‘There’s always been a strange kind of bond between us’, Julia says in reference to her sister, ‘It’s taken me nearly seven years of being totally cut off from her to get over it’. When Julia attempts to confide in James the cruelty she suffered at the hands of Mary, James pooh-poohs her claims, suggesting they are a fabrication.  Exacerbating the film’s Gothic heritage, Julia’s landlady – who claims to be psychic, though the film does surprisingly little with this suggestion of her extra-sensory powers – explains that the house was once a funeral parlour. It was owned by her great grandfather who, she says, shipped Mr Kimura’s great grandfather to America along with an elephant; ‘He [Mr Kimura’s great grandfather] never did say thank you’, she chunters, pointing at a theme of cultural ignorance and the unwillingness of the powerful to empathise with the disempowered. Exacerbating the film’s Gothic heritage, Julia’s landlady – who claims to be psychic, though the film does surprisingly little with this suggestion of her extra-sensory powers – explains that the house was once a funeral parlour. It was owned by her great grandfather who, she says, shipped Mr Kimura’s great grandfather to America along with an elephant; ‘He [Mr Kimura’s great grandfather] never did say thank you’, she chunters, pointing at a theme of cultural ignorance and the unwillingness of the powerful to empathise with the disempowered.

Uncle James and Sam are representatives of patriarchal authority, disbelieving of Julia’s tales of her abuse at the hands of Mary and unwilling to believe Julia’s claims that Mary has threatened and assaulted her in the hospital. To some extent, James and Sam are complicit in the victimisation of Julia by her twin sister. However, Sam has greater doubt about the position from which he starts, gradually coming to believe Julia’s stories. Meanwhile, Uncle James delivers a sermon from his pulpit which threatens divine punishment for those who fail to fulfil their ‘responsibilities’ to their siblings, to act as their ‘brother’s (or sister’s) keeper’; James’ authority is divine, reinforced by the ultimate hierarchy. ‘It is the family that creates on this earth the closest approximation of the wonderful love of heaven’, James insists during his sermon, which becomes increasingly direct in its criticism of Julia’s relationship with her sister: ‘“How great,” might a wrathful God ask, “shall my love be for that sibling who has denied her sister the tender care of a friend or companion or nurse?” […] I say unto you, how terrible shall be His vengeance on those that do not confess their selfishness before He who is most giving of perfect familial love, for they have offended Him mightily’. When Julia suggests Mary may be guilty of the murder of Sacha, James denies this: ‘I think it’s guilt that’s inducing these wild accusations’, he says, suggesting that Julia is delusional. He continues: ‘Often, what we imagine will happen. Visions can seem very real’. However, as the film moves towards its conclusion, James is revealed to be in cahoots with Mary, assisting in her victimisation of Julia: patriarchal authority is thus revealed to be not just complicit in the persecution of Julia, but an active and willing agent in her torment. At the film’s climax, Julia is torn between two male symbols of authority: Sam, her lover, who has come to rescue her; and James, her uncle and father figure, who is attempting to kill her (or, at the very least, drive her to the same pit of insanity in which her twin sister Mary dwells). In its open challenge to repressive systems of authority, Madhouse runs contra to the oft-repeated (and reductive) suggestion that slasher films are largely reactionary and concerned with the depiction of conservative forces teaching young people to ‘know their place’ and not to challenge the status quo.  The film builds towards the birthday of Julia and Mary, the inevitability of this event – and its status as the film’s climax – being represented through a series of title cards that essentially count down to the date. Like J Lee Thompson’s Happy Birthday to Me, Madhouse features at its climax a macabre and perverse ‘party’ in which a group of corpses are arranged around a table in mock celebration of the protagonist’s birthday. The denouement erupts in an explosion of violence which, in its emphasis on overkill with an axe and its suggestion that the female protagonist has had an encounter with the abyss from which she will never recover, bears some strong similarities to the climax of Michael Reeves’ Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (1968) – in which Ian Ogilvy’s protagonist, Roundhead soldier Richard Marshall, displays a similar level of intolerable cruelty as the film’s villain, Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price), leading Marshall’s lover Sara (Hilary Dwyer) to scream hysterically, her sense of reality shattered forever. The film builds towards the birthday of Julia and Mary, the inevitability of this event – and its status as the film’s climax – being represented through a series of title cards that essentially count down to the date. Like J Lee Thompson’s Happy Birthday to Me, Madhouse features at its climax a macabre and perverse ‘party’ in which a group of corpses are arranged around a table in mock celebration of the protagonist’s birthday. The denouement erupts in an explosion of violence which, in its emphasis on overkill with an axe and its suggestion that the female protagonist has had an encounter with the abyss from which she will never recover, bears some strong similarities to the climax of Michael Reeves’ Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (1968) – in which Ian Ogilvy’s protagonist, Roundhead soldier Richard Marshall, displays a similar level of intolerable cruelty as the film’s villain, Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price), leading Marshall’s lover Sara (Hilary Dwyer) to scream hysterically, her sense of reality shattered forever.

Video

The presentation takes up approximately 28Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is uncut, with a running time of 93:20 mins. ( Shot in Technovision on colour 35mm film, Madhouse is here presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. (Technovision was an anamorphic process developed in the early 1970s by Henryk Chroscicki and based on Chroscicki’s earlier process Totalscope, the process in which Fellini shot La Dolce Vita in 1960.) The presentation takes up approximately 28Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is uncut, with a running time of 93:20 mins. ( Shot in Technovision on colour 35mm film, Madhouse is here presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. (Technovision was an anamorphic process developed in the early 1970s by Henryk Chroscicki and based on Chroscicki’s earlier process Totalscope, the process in which Fellini shot La Dolce Vita in 1960.)

The presentation is based on a new 2k restoration from the negative. From the opening shot, which features deep black shadows surrounding a spot-lit image of a girl rocking another girl in a rocking chair (before the first girl smashes a rock into the face of the second girl, turning it into a bloody pulp), contrast levels are impressive. Midtones have strong definition to them, highlights are evenly balanced, and blacks are deep. A rich level of detail is present throughout the film (though, owing to the characteristics of the lenses, the image is sharper in the middle, this sharpness tapering off at the periphery of the frame). Soft focus photography and diffuse light are used in the close-ups of Trish Everly, which can sometimes be a little jarring when these shots are cut against more harshly light and contrasty close-ups of other actors in the same scenes; but this is a characteristic of the film’s original photography, represented accurately here. Skintones are naturalistic and, elsewhere, colours are vibrant without seeming artificial: for example, the bright red of the children’s sweatshirts in the film’s post-credits opening sequence. There is no distracting damage present in the film, and no evidence of harmful digital tinkering. A strong encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film.

NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via either (1) a LPCM 2.0 stereo track, or (2) a DTS-HD MA 5.1 track. Both tracks are clear throughout and demonstrate a strong sense of range; though the 5.1 track features added sound separation, it feels a little synthetic. Viewers may notice that Riz Ortolani’s score reiterates some of the tense cues Ortolani scored for Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust (1979). Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are provided. These are easy to read and largely free from errors – though noticeably, Sacha’s name is spelt differently at various times in the subtitles (mostly as ‘Sacha’ but sometimes as ‘Sasha’).

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with The Hysteria Continues. The film is accompanied by a commentary track by the chaps of The Hysteria Continues podcast. I’m a big fan of these commentaries, as they’re entertaining and informative for both seasoned fans of the genre and for newcomers. The group offer personal reflections on the film, and they discuss its reception and various home video releases. They also reflect on the cast and crew, and the relationship between Madhouse and other examples of the genre. It’s a fun, engaging commentary track that is packed with information and insight. - ‘Running the Madhouse’ (12:40). This new interview with Edith Ivey sees the actress reflecting on her career, and expressing surprise that of all the films she made, Madhouse is one ‘that people are interested in’. Ivey talks about her origins in radio and her transition into television and film acting. She reveals that because the film’s ‘entire crew was from Italy and spoke no English’, on the set was an ‘associate director from Scotland’ who interpreted everything Assonitis wanted to say into English for the English-speaking actors. Assonitis wanted the actors to perform in an ‘over the top’ fashion, and ‘that’s what we all tried to do as best as we could’. Dennis Robertson was, she says, ‘embarrassed to be in a slasher movie’. Ivey’s recollections are vivid and interesting, and the interview is fascinating throughout. - ‘Framing Fear’ (19:32). In another new interview, the film’s cinematographer, Roberto D’Ettorre Piazzoli, discusses his contribution to the picture. Piazzoli discusses his early work as an assistant on the set of one of Elio Petri’s films. He reflects on his first encounter with Assonitis. Piazzoli talsk about the popularity of Italian cinema during the 1980s and the reasons for that decline in the late 1980s/early 1990s. This interview situates Madhouse within the context of Italian cinema of the period. He talks about the shooting of the picture and the use of the Kehoe house as a location, reflecting on the rumours that the house was haunted and reminding the viewer that Fulci shot some scenes for Paura nella citta dei morti viventi (City of the Living Dead, 1980) in the same building. The interview is in Italian with optional English subtitles. - ‘Ovidio Nasty’ (7:44). Assonitis reflects on Madhouse, discussing the origins of the project and his relationship with the horror genre. Assonitis’ comments come across like a pitch for the film, perhaps reflecting his past as a producer and distributor of films. He reveals that his preferred title for the film is is There Was a Little Girl. He suggests that the film was influenced by William Dieterle’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923), Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinett des Dr Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, 1920) and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1979). He talks about the Kehoe house and their decision to use it as a location, and he also reflects on the casting. Assonitis speaks in English. - Alternate Opening Titles (3:01). This alternate opening titles sequence is essentially the same as that in the main feature, except here we see Assonitis’ preferred title There Was a Little Girl used onscreen. - Trailer (3:04). Retail copies include reversible sleeve artwork and a booklet.

Overall

A Gothic melodrama rather than ‘video nasty’, with echoes of the story of Cain and Abel, Madhouse is an interesting but not entirely successful film. The setpieces are handled well, and the hysteria of Mary is communicated excellently and memorably through Allison Biggers’ performance. Though the story is intimate, the widescreen photography gives the film a sense of grandeur and allows the filmmakers to use the interior spaces in a manner that communicates threat and generates unease. The ‘twist’ will be spotted by even the most casual first-time viewer towards the beginning of the film; it’s arguably less a twist than a chilling inevitability. A Gothic melodrama rather than ‘video nasty’, with echoes of the story of Cain and Abel, Madhouse is an interesting but not entirely successful film. The setpieces are handled well, and the hysteria of Mary is communicated excellently and memorably through Allison Biggers’ performance. Though the story is intimate, the widescreen photography gives the film a sense of grandeur and allows the filmmakers to use the interior spaces in a manner that communicates threat and generates unease. The ‘twist’ will be spotted by even the most casual first-time viewer towards the beginning of the film; it’s arguably less a twist than a chilling inevitability.

Like Assonitis’ previous ‘Americanised’ films, Madhouse is unconvincing in its depiction of American culture, feeling an awful lot like other contemporaneous films made by Italian crews in America (for example, Fulci’s The Beyond). Also like Assonitis’ previous pictures, the film shows the strong influence of other films, from American slasher films to pictures about ‘haunted’ apartment buildings (for example, Michael Winner’s 1977 horror film The Sentinel). The climax is strikingly similar to that of J Lee Thompson’s Happy Birthday to Me – though it’s unclear which film was made first, or if this is just a case of strange synchronicity – and the whole thing is topped off by a literary quote that is misattributed to George Bernard Shaw. Fans of slasher films will find Madhouse to be a worthwhile picture. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release contains a very impressive presentation of the main feature and an excellent array of contextual material.

|

|||||

|