|

|

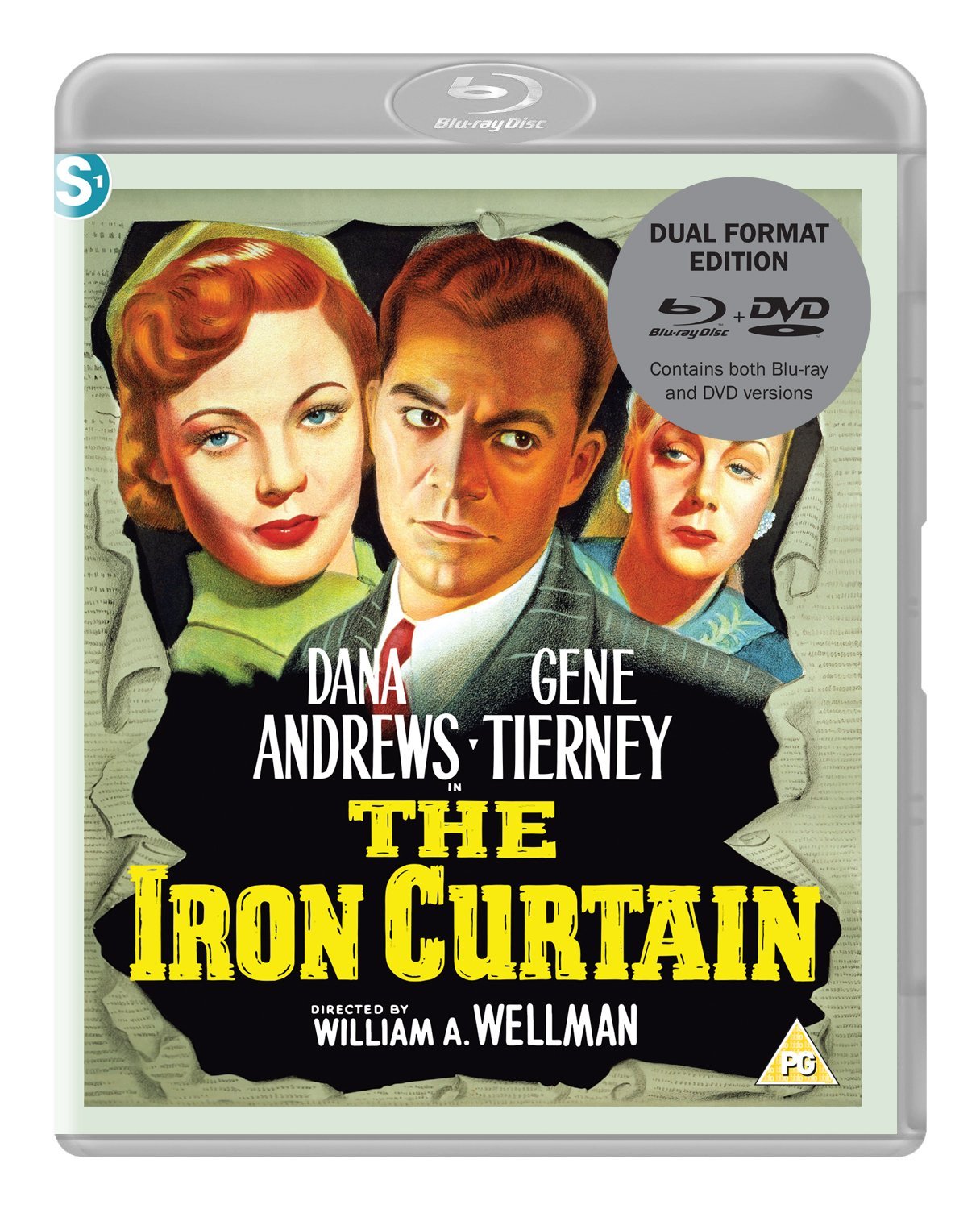

Iron Curtain (The) AKA Behind the Iron Curtain (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (26th April 2017). |

|

The Film

The Iron Curtain (William A Wellman, 1948) The Iron Curtain (William A Wellman, 1948)

Where in the early 1940s, Hollywood had produced a number of pro-Russian films with the intention of showing the public that Russia was an ally in the war against Hitler (for example, Michael Curtiz’s Mission to Moscow, 1943, based on the memoirs of the former US ambassador to Russia, Joseph E Davies), by the end of the decade and into the 1950s Hollywood became fixated on making pictures that showed Soviet ideology to be a particularly insidious menace; much as the early films of the wartime era depicted Nazi spies infiltrating American soil (for example, Vincent Sherman’s Humphrey Bogart-starring All Through the Night from 1942), these later anti-Soviet films often showed Russia to be attempting to plant the seeds of a Communist plot of subversion within the United States. William A Wellman’s The Iron Curtain (1948) was one of the first of such pictures, paving the way for later films including The Red Menace (R G Springsteen, 1949), I Was a Communist for the FBI (Gordon Douglas, 1951), Whip Hand (William Cameron Menzies, 1951) and Big Jim McLain (Edward Ludwig, 1951) – the latter famously being the film in which John Wayne and James Arness portray House Un-American Activities Commission investigators who journey to Hawaii to hunt down American members of the Communist Party. The Iron Curtain is based on the true story of Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko; tasked by his employers with working within the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, encoding messages from Russian spies within Canada and the US before their transmission to Moscow, Gouzenko defected to the West only three days after the end of the Second World War. Gouzenko’s defection, and his allegations that members of Canada’s political landscape were passing secrets to Russia, sparked a Royal Commission focusing on Soviet espionage in Canada; this Royal Commission led to the trials of twenty people and the revelation that Soviet spies were present in Canada and the US during wartime, some of them (such as Alan Nunn May, convicted of espionage in 1946) even operating within the Manhattan Project. The fallout from the ‘Gouzenko Affair’ helped to precipitate anti-Communist sentiment within the US, leading to the conviction of the Rosenbergs in 1951 and the McCarthy hearings that echoed throughout the decade and were intended to ‘root out’ subversive elements.  In the film, Gouzenko is played by Dana Andrews. The picture’s opening sequences show Gouzenko arriving in Ottawa, where he is briefed at the Soviet embassy. Gouzenko is shown to an office where he is to function as a cipher clerk, encoding messages from Soviet spies monitoring the atomic research project in preparation for their transmission to Moscow. Gouzenko becomes aware of the intentions of the Soviet government to build a large network of spies within the Canadian government. In the film, Gouzenko is played by Dana Andrews. The picture’s opening sequences show Gouzenko arriving in Ottawa, where he is briefed at the Soviet embassy. Gouzenko is shown to an office where he is to function as a cipher clerk, encoding messages from Soviet spies monitoring the atomic research project in preparation for their transmission to Moscow. Gouzenko becomes aware of the intentions of the Soviet government to build a large network of spies within the Canadian government.

After a period of time, Gouzenko is joined by his wife Anna (Gene Tierney). It is a happy reunion, and soon Anna reveals she is pregnant. When he is tasked with encoding an important communique about the American nuclear programme, Gouzenko misses the birth of his son. Soon he is also asked to encode messages explaining the nuclear programme from a British scientist named Dr Norman (Nicholas Joy; a thinly-veiled allusion to Alan Nunn May). When the atomic bombs are dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, Gouzenko becomes aware of the destructive potential of the data he has been encoding. With Anna and his baby son, Igor decides to defect, approaching the Canadian government; however, they believe his story of Soviet spies embedded within positions of power to be too incredible to be true. Gouzenko then decides to take his story to the press, but he is told ‘If the government won’t touch it, it’s too big for us too’. Finally, he approaches the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, just as the Soviets become aware of Gouzenko’s defection and begin to close in on Gouzenko and his family with the intention of eliminating Igor, Anna and their baby son. As a film, The Iron Curtain ‘set the tone for a whole new genre of anti-Communist Hollywood films’ (Leab, cited in Starck, 2016: 69). In fact, critic Bosley Crowther referred to the picture as ‘Hollywood’s first shot in the Cold War’ (Crowther, quoted in ibid.: 72). Made in the late 1940s, The Iron Curtain evidences some of the traits of both the then-popular social problem picture and post-war semidocumentary films noir such as The House on 92nd Street (Henry Hathaway, 1945) and The Naked City (Jules Dassin, 1948). Like the semidocumentary films noir, The Iron Curtain employs some of the techniques associated with newsreels, including a voiceover by an extradiegetic, third person narrator (Reed Hadley, who had also narrated The House on 92nd Street) and a heavy emphasis on location shooting, the opening credits proudly declaring that as much of the film as possible was shot on the real locations in Canada where the events depicted in the narrative took place. The film also features characteristically film noir-style photography, making much use of obtuse low and high-angle shots and employing a great deal of chiaroscuro lighting within its aesthetic. An onscreen title as the film opens foregrounds the picture’s basis in a true story, telling the audience ‘This story is based on the Royal Commission June 27, 1946, and evidence presented in Canadian Courts that resulted in the conviction of ten secret agents of the Soviet Government’.  In a 2006 essay about anti-Soviet pictures made in Hollywood during the era in which The Iron Curtain was produced, Reynold Humphries has highlighted some of the ways in which The Iron Curtain alludes to the visual and thematic/narrative conventions of film noir, highlighting in particular the sequence in which Gouzenko’s boss’ secretary attempts to seduce him, as a means of assessing how vulnerable Gouzenko is to ‘turning’, as ‘resort[ing] to the film noir character of the femme fatale’ (Humphries, 2006: 109). When, later in the film, the Soviet agents arrive at Gouzenko’s apartment with the intention of assassinating him, Humphries argues that The Iron Curtain makes some direct visual allusions to the opening sequence of Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946), in which two hoodlums (William Conrad and Charles McGraw) arrive in the small town of Summit to assassinate the Swede (Burt Lancaster) (ibid.). In a 2006 essay about anti-Soviet pictures made in Hollywood during the era in which The Iron Curtain was produced, Reynold Humphries has highlighted some of the ways in which The Iron Curtain alludes to the visual and thematic/narrative conventions of film noir, highlighting in particular the sequence in which Gouzenko’s boss’ secretary attempts to seduce him, as a means of assessing how vulnerable Gouzenko is to ‘turning’, as ‘resort[ing] to the film noir character of the femme fatale’ (Humphries, 2006: 109). When, later in the film, the Soviet agents arrive at Gouzenko’s apartment with the intention of assassinating him, Humphries argues that The Iron Curtain makes some direct visual allusions to the opening sequence of Robert Siodmak’s The Killers (1946), in which two hoodlums (William Conrad and Charles McGraw) arrive in the small town of Summit to assassinate the Swede (Burt Lancaster) (ibid.).

Humphries also suggests that the fact that, within the Soviet embassy, the iron door which seals the code clerks off from the rest of the embassy is hidden behind a velvet curtain is a metaphor for ‘standard devious Soviet methods’ (the iron fist concealed within a velvet glove) (ibid.). On a more comical note, Humphries discusses the scene in which Gouzenko is called away from his wife during the night, and in response Anna tells him ‘I’ll keep the bed warm’ – but of course, owing to the demands of the Motion Picture Production Code, the pair are shown sleeping in separate beds. ‘[O]ne can only feel sympathy for the poor woman’, Humphries writes, ‘having to spend the night going from one bed to the other to keep her promise to her husband’ (ibid.). Ultimately, Humphries argues, The Iron Curtain ‘is a typical piece of Hollywood fiction where the usual codes are re-fashioned and re-furbished to carry the necessary anti-Communist message’ (ibid.).  As a project, The Iron Curtain was put together by Darryl F Zanuck, who was inspired by a speech made by J Edgar Hoover that warned of active Soviet spies within the US. The story outline was assembled by Martin Berkeley, a former member of the Communist Party who became a fervent anti-Communist, providing the House Un-American Activities Commission with over 150 names of Communist Party members and Communist sympathisers and becoming the HUAC’s most ‘friendly’ collaborator. The writer of The Iron Curtain’s screenplay, Milton Krims, had previously penned a similar script about Nazi spies operating within America for the 1939 picture Confessions of a Nazi Spy, and The Iron Curtain represents its Soviet agents in a very similar manner to which Nazi spies had been presented in wartime pictures – as clandestine agents, smoking cigarettes in sinister ways behind closed doors. The film critic for The New York Times declared that The Iron Curtain ‘is the 1948 version of “Confessions of a Nazi Spy”’ and is ‘every bit as blunt [as that film] in its arraignment of the Russian people and their ideology. Only this time […] the arch-villains are not the ambitious lords of the Wilhelmstrasse; they are the silent men of the Kremlin who command rings of spies […] and whose obviously evil intention is to destroy capitalism and rule a Communist world’ (quoted in Blackmur, 1993: 179). As a project, The Iron Curtain was put together by Darryl F Zanuck, who was inspired by a speech made by J Edgar Hoover that warned of active Soviet spies within the US. The story outline was assembled by Martin Berkeley, a former member of the Communist Party who became a fervent anti-Communist, providing the House Un-American Activities Commission with over 150 names of Communist Party members and Communist sympathisers and becoming the HUAC’s most ‘friendly’ collaborator. The writer of The Iron Curtain’s screenplay, Milton Krims, had previously penned a similar script about Nazi spies operating within America for the 1939 picture Confessions of a Nazi Spy, and The Iron Curtain represents its Soviet agents in a very similar manner to which Nazi spies had been presented in wartime pictures – as clandestine agents, smoking cigarettes in sinister ways behind closed doors. The film critic for The New York Times declared that The Iron Curtain ‘is the 1948 version of “Confessions of a Nazi Spy”’ and is ‘every bit as blunt [as that film] in its arraignment of the Russian people and their ideology. Only this time […] the arch-villains are not the ambitious lords of the Wilhelmstrasse; they are the silent men of the Kremlin who command rings of spies […] and whose obviously evil intention is to destroy capitalism and rule a Communist world’ (quoted in Blackmur, 1993: 179).

The release of The Iron Curtain was met with protests by pro-Soviet groups who clashed with anti-Communist protestors. An article published in Life magazine at the time of the film’s original release proclaimed The Iron Curtain to be the ‘first movie to take a strong stand against the current aggressive action of the Soviet Union’ (Life, 1948: 59). The article notes that the picture ‘is already stirring up a storm of leftist criticism’, adding that The Iron Curtain conveys ‘[t]he fanaticism, suspicion and amorality which characterize the Communist mind’ in a manner that is ‘more graphic and hideous […] than in a hundred editorials’ (ibid.). In typically inflammatory language, the piece documents the immediate response to the film, arguing that The Iron Curtain is ‘from the Communist point of view, a movie that hurts. Communists even tried to stop it. The producers were threatened by strikes if they tried to make it. Location scenes in Ottawa were visited by local Reds who hooted in order to spoil the sound track’ (ibid.) After the shooting of the picture was completed, Life asserts, ‘a new campaign began to stop its release […] Theaters showing the picture this week will undoubtedly be picketed and boycotted by Communists and militant left-wingers’ (ibid.). The article notes that one of the main organisations critical of The Iron Curtain was the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship, headed by Rev. William Melish, who ‘publicly denounced The Iron Curtain (which he had not yet seen) as “war propaganda”’ and asserted that the film was ‘a “flagrant violation” of the U.N. resolution condemning warmongering’ (ibid.: 60). Life reminds its viewers that the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship was ‘called “subversive” by Attorney General Tom Clark’ (ibid.). The campaign of Melish’s organisation led to ‘8,000 letters, telegrams and postcards […] from people who could not possibly have seen [the film]’ being sent in protest to Fox’s New York offices: the impact of this, Life says, is ‘an impressive display of how easily Communist-line organizations can muster support for even the most obscure left-wing causes’ (ibid.).  The film itself criticises such organisations directly: within The Iron Curtain, the Soviets are shown using The Associated Friends of Soviet Russia as a ‘front operation’ that functions as, in the words of the narrator, ‘a showcase for potential agents’. The film presents its audience with a subplot involving a member of the Canadian Air Force, Captain Donald Class (Victor Wood), who is spotted at a meeting of The Associated Friends of Soviet Russia and marked by the Russian agents as a man who may be ‘turned’ to their cause. ‘There were also small private gatherings, known as “study groups”’, the narrator says, where the writings of Lenin, Marx, etc, were examined’. At one of these ‘study groups’, Class is approached by a member of the Canadian government, Leonard Leitz (Mauritz Hugo), who tells Class that ‘All kinds of people come to these study groups […] First there are the talkers […] For some, Marxism is a kind of a game they play to rid them of their frustrations. To others, it’s a kind of a fashionable cult [….] Then there are the doers. They never have much to say. One can feel in them the fanaticism of the true believer [….] Unfortunately, there are not too many “doers”’. Class is soon shown to be recruited into the ranks of embedded Soviet agents. The film itself criticises such organisations directly: within The Iron Curtain, the Soviets are shown using The Associated Friends of Soviet Russia as a ‘front operation’ that functions as, in the words of the narrator, ‘a showcase for potential agents’. The film presents its audience with a subplot involving a member of the Canadian Air Force, Captain Donald Class (Victor Wood), who is spotted at a meeting of The Associated Friends of Soviet Russia and marked by the Russian agents as a man who may be ‘turned’ to their cause. ‘There were also small private gatherings, known as “study groups”’, the narrator says, where the writings of Lenin, Marx, etc, were examined’. At one of these ‘study groups’, Class is approached by a member of the Canadian government, Leonard Leitz (Mauritz Hugo), who tells Class that ‘All kinds of people come to these study groups […] First there are the talkers […] For some, Marxism is a kind of a game they play to rid them of their frustrations. To others, it’s a kind of a fashionable cult [….] Then there are the doers. They never have much to say. One can feel in them the fanaticism of the true believer [….] Unfortunately, there are not too many “doers”’. Class is soon shown to be recruited into the ranks of embedded Soviet agents.

On the other hand, other publications criticised the pictures simplistic approach to espionage, the Mail asserting dryly ‘Remember those over-simplified grotesque Nazis we got so tired of in American, British and Russian films? Well, we’ve inherited them again as Russians’ (quoted in Starck, op cit.: 70). Elsewhere, the Sunday Express asserted that the makers of The Iron Curtain ‘seem […] to be monstrously shocked that the Soviet government has agents in Canada and America finding out what is going on about atomic warfare. I can only say that I shall be monstrously shocked if our own and the Americans are not similarly enquiring about the East’ (quoted in ibid.: 71). For most of the film, Andrews plays Gouzenko with a sense of steely impassivity. When he is briefed at the Soviet embassy upon his arrival in Ottawa, Gouzenko is told he must ‘eat, sleep, think those answers’ to the questions he may be posed by the ‘enemy’: Gouzenko is presented with a cover story which erases his experience in the Soviet army during the Second World War, told to masquerade as a cipher clerk with no military experience whatsoever. ‘You will be wise not to forget that even on foreign soil, you are a Soviet citizen… and soldier’, Gouzenko is reminded. He is taken to the office in which he must work, where hanging on a wall is a portrait of Stalin, the eyes of which seem to follow Gouzenko around the room – a constant reminder of the ideology to which he is committed and must conform. ‘When your day’s work is done’, Gouzenko is told by the guard, ‘every single scrap of paper must be burnt. And don’t ask to have the music turned off. It’s a rule. The music must always play, so no-one can hear what’s being said in the other offices’.  Gouzenko’s boss’ secretary, Nina (June Havoc), is tasked with attempting to seduce Gouzenko, in a manner which is intended to assess how easily Gouzenko may or may not be ‘turned’ by the enemy in a ‘honey trap’ scenario. She takes Gouzenko to a dance hall before returning with him to her apartment. Gouzenko is amazed at the luxury of Nina’s home: ‘This is good enough for our Commissar’, he says, ‘Living must be cheap here’. ‘You’re in Canada’, Nina tells him before adding by way of a come-on, ‘There’s plenty of everything’. Gouzenko reacts to her attempt at seduction with a buttoned-up rebuttal: ‘I’m a very important person’, he says, ‘with all kinds of secrets. I’ll tell you one: my wife is very beautiful’. He continues, telling Nina ‘You’re not very clever. You’ve been away from Russia too long. Experience has provided new techniques […] For one thing, never ask direct questions; and for another, you should never bring a Russian to a place like this for questioning: it might dull the wits of these Canadians, but for a Russian it means only one thing’. Gouzenko’s boss’ secretary, Nina (June Havoc), is tasked with attempting to seduce Gouzenko, in a manner which is intended to assess how easily Gouzenko may or may not be ‘turned’ by the enemy in a ‘honey trap’ scenario. She takes Gouzenko to a dance hall before returning with him to her apartment. Gouzenko is amazed at the luxury of Nina’s home: ‘This is good enough for our Commissar’, he says, ‘Living must be cheap here’. ‘You’re in Canada’, Nina tells him before adding by way of a come-on, ‘There’s plenty of everything’. Gouzenko reacts to her attempt at seduction with a buttoned-up rebuttal: ‘I’m a very important person’, he says, ‘with all kinds of secrets. I’ll tell you one: my wife is very beautiful’. He continues, telling Nina ‘You’re not very clever. You’ve been away from Russia too long. Experience has provided new techniques […] For one thing, never ask direct questions; and for another, you should never bring a Russian to a place like this for questioning: it might dull the wits of these Canadians, but for a Russian it means only one thing’.

Later, after Anna arrives in Canada, Gouzenko tells her that they should not fraternise with the locals, reacting angrily after he finds Anna has invited their neighbour Mrs Foster (Edna Best) into their home. (‘We must not fraternise with Canadians. We must do as we’re told’, Gouzenko asserts.) Anna expresses doubts about the ideology to which Gouzenko has committed himself, but her husband silences her. Together, Igor and Anna are shown exploring Canada, wandering the city streets and visiting the countryside; the narrator tells us that the couple are exploring ‘what was for them a strange, sometimes disturbing, sometimes puzzling world’. Gouzenko criticises Western culture, suggesting that the lack of authoritarian ‘leadership’ within Canada is a failing of the culture and telling Anna ‘The fact is, these people are politically uneducated. They have no leadership to help them think’. However, with the birth of his son – which Gouzenko misses owing to the fact that he has been tasked with composing a coded message to Moscow whilst his wife is giving birth – Gouzenko begins to become more ‘human’, the growth in his emotional responses occurring concurrently with his dissatisfaction with his Soviet employers. Like many of the pictures that came after it, The Iron Curtain draws a parallel between regimented automaton-like behaviour and Soviet ideology, the protagonist’s alienation from the latter developing out of the increased range in his emotional responses to the world around him. Gouzenko’s decision to defect comes when he realises the destructive potential of the nuclear research he has been encoding for transmission to Moscow, deciding that he no longer wishes to participate in an ideology which may cause devastation to the life of his young son. ‘I must think for him [his baby son]’, Igor tells Anna before he hatches his plan to defect, ‘I must tell him what kind of world I want him to live in, what kind of man I want him to be. Some day I’ll have to answer to him, and I want to be able to face him without being afraid or ashamed’.

Video

The Iron Curtain is presented in its original Academy screen ratio of 1.33:1. The film is uncut, with a running time of 86:28 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 21Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 35mm monochrome photography features film noir-style chiaroscuro light and obtuse angles. The high contrast photography is rendered very well here, contrast being extremely pleasing. Deep blacks are balanced by strongly defined mid-tones and equalised highlights. There are some beautiful shots of characters in darkness, their outlines framed by light coming from a backlight, the effect producing a halo of light. Such shots are presented very impressively here – in a manner that far exceeds the capabilities of the DVD format. The image is clean, with little to no damage present throughout (other than a handful of fine vertical lines, notoriously difficult to remove, that appear here and there), the photography rendered within this digital presentation with depth and definition. Finally, an excellent encode ensures the presentation retains its crisp, film-like texture, capturing the structure of 35mm film. The Iron Curtain is presented in its original Academy screen ratio of 1.33:1. The film is uncut, with a running time of 86:28 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 21Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The 35mm monochrome photography features film noir-style chiaroscuro light and obtuse angles. The high contrast photography is rendered very well here, contrast being extremely pleasing. Deep blacks are balanced by strongly defined mid-tones and equalised highlights. There are some beautiful shots of characters in darkness, their outlines framed by light coming from a backlight, the effect producing a halo of light. Such shots are presented very impressively here – in a manner that far exceeds the capabilities of the DVD format. The image is clean, with little to no damage present throughout (other than a handful of fine vertical lines, notoriously difficult to remove, that appear here and there), the photography rendered within this digital presentation with depth and definition. Finally, an excellent encode ensures the presentation retains its crisp, film-like texture, capturing the structure of 35mm film.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 track. This is clean and clear throughout, dialogue being always audible. Sadly there are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc contains no extra features whatsoever. A DVD copy of the film is included in the package, however.

Overall

The Iron Curtain is openly propagandistic, one of the first broadsides fired by Hollywood in what would develop into the Cold War. The film refers to the paradigms of the pictures about embedded Nazi spies that were popular during the Second World War, substituting Soviet agents for the Nazis; this material is communicated through the lens of the techniques used within semidocumentary films noir - the use of an extradiegetic narrator; the use of newsreel footage and real locations. It’s a manipulative narrative that is given depth by the performances of Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney, their shared presence perhaps reminding the viewer of the roughly contemporaneous films noir in which they starred together, such as Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944) and Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950). The story is also carried by some striking photography by Charles G Clarke; Clarke’s work on this film gives The Iron Curtain the appearance of a film noir. Certainly, it’s an entertaining film, a document of its time. Signal One’s Blu-ray contains a very impressive presentation of the main feature. The Iron Curtain is openly propagandistic, one of the first broadsides fired by Hollywood in what would develop into the Cold War. The film refers to the paradigms of the pictures about embedded Nazi spies that were popular during the Second World War, substituting Soviet agents for the Nazis; this material is communicated through the lens of the techniques used within semidocumentary films noir - the use of an extradiegetic narrator; the use of newsreel footage and real locations. It’s a manipulative narrative that is given depth by the performances of Dana Andrews and Gene Tierney, their shared presence perhaps reminding the viewer of the roughly contemporaneous films noir in which they starred together, such as Otto Preminger’s Laura (1944) and Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950). The story is also carried by some striking photography by Charles G Clarke; Clarke’s work on this film gives The Iron Curtain the appearance of a film noir. Certainly, it’s an entertaining film, a document of its time. Signal One’s Blu-ray contains a very impressive presentation of the main feature.

References: Blackmur, Douglas, 1993: Strikes: Causes, Conduct & Consequences. Sydney: The Federation Press Humphries, Reynold, 2006: ‘“Documenting” Communist Subversion: The Case of I Was a Communist for the F.B.I. (1951)’. In: Rhodes, Gary D & Springer, John Paris (eds), 2006: Docufictions: Essays on the Intersection of Documentary and Fictional Filmmaking. London: McFarland & Company: 102-23 Life, 1948: ‘“The Iron Curtain” Creates a Furor’. Life (17 May, 1948): 59-62 Starck, Kathleen, 2016: Of Treason, God and Testicles: Political Masculinities in British and American Films of the Early Cold War. Cambridge Scholars Publishing

|

|||||

|