|

|

Tower of London (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (18th February 2017). |

|

The Film

Tower of London (Roger Corman, 1962) Tower of London (Roger Corman, 1962)

Beginning in 1483, with Edward IV (Justice Watson) on his deathbed, Roger Corman’s Tower of London (1962) opens with Edward addressing his family, praising his brother Richard’s (Vincent Price) positive influence during a time of turmoil. However, when Edward names his other brother, George, the Duke of Clarence (Charles Macauley), as Protector of the Realm and informs his sons that following his death, they will be kept in the care of George until the eldest of them is old enough to take the throne, Richard exhibits jealousy. Alone with George, Richard sinks a dagger into his brother’s back before dumping the corpse in a vat of wine. George’s disappearance is noted; in private, Richard’s wife Anne condones the murder of George, committed in service of Richard’s ambition and his desire to claim the throne for himself. When George’s body is found, Richard plants a dagger bearing the crest of the Woodville family, leading to a widespread belief that the murder of George was committed by the family of Edward’s wife Elizabeth Woodville; this escalates the feud between the Plantagenets and the House of Lancaster. Following the murder of George, Edward names Richard the new Protector of the Realm. However, Richard is shocked when he is visited by the ghost of George, who warns Richard that he will ‘die in violence, at the hand of a man already dead’. When Richard tells his wife Anne that he has seen the ghost of George on the battlements, she ridicules him.  In an attempt to secure the throne for himself, Richard plots the murder of his two young nephews, enlisting the help of Sir Ratcliffe (Michael Pate). Before doing this, however, Richard attempts to persuade their nanny, Mistress Shore (Sandra Knight), to suggest publicly that the young princes were sired by someone other than Edward. When Shore refuses, Richard has her taken to the dungeons and tortured. In an attempt to secure the throne for himself, Richard plots the murder of his two young nephews, enlisting the help of Sir Ratcliffe (Michael Pate). Before doing this, however, Richard attempts to persuade their nanny, Mistress Shore (Sandra Knight), to suggest publicly that the young princes were sired by someone other than Edward. When Shore refuses, Richard has her taken to the dungeons and tortured.

When Shore dies, Richard is visited by her ghost; driven to anger by Shore’s ghost’s suggestion that Richard will die by ‘a ghostly weapon’, Richard attempts to throttle Shore but discovers that he has instead strangled his own wife, Anne. With Anne dead, Richard becomes increasingly disturbed by the visits he receives from the dead. Meanwhile, Richard’s enemies begin to plot against him. The film was originally announced under the title ‘A Dream of Kings’ and was intended as a loose remake of the 1939 picture Tower of London (directed by Rowland V Lee and featuring Basil Rathbone as Richard III). In his third screen role, Vincent Price had appeared in the 1939 film, playing George, Duke of Clarence. Where the 1939 film was a historical melodrama, Corman’s version of the story uses the historical events as a springboard for a narrative that has more in common with the director’s Gothic adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe’s stories.  Tower of London opens with a solemn and portentous moment of narration accompanied by a miniature shot of the titular tower, which here is represented as a symbol of some of the worst aspects of human nature: ‘The Tower of London’, the narrator intones, ‘A monument to the corruption of the soul, where in the shadowed past a man came to the throne of England despite the insane ambition that drove him to evil and murder. He escaped the headsman’s block but he could never escape the ghosts of his conscience’. The film’s focus on the Tower of London as a symbol of ‘the corruption of the soul’ links the picture to the archetypes explored in Corman’s Gothic films, in particular the representation of Roderick Usher’s house as a symbol of Usher’s soul in The Fall of the House of Usher (Corman, 1960). The visits upon Richard by ghosts of those whose lives have been sacrificed to his ambition, and the ambiguity that surrounds these visitations (are they real, or are they a product of Richard’s paranoia?), also connects Tower of London to Corman’s horror films, as does the sequence in which Tyrus (Richard Hale) attempts to ‘call out’ these ‘evil spirits’ via the enactment of a paganistic rite. Tower of London opens with a solemn and portentous moment of narration accompanied by a miniature shot of the titular tower, which here is represented as a symbol of some of the worst aspects of human nature: ‘The Tower of London’, the narrator intones, ‘A monument to the corruption of the soul, where in the shadowed past a man came to the throne of England despite the insane ambition that drove him to evil and murder. He escaped the headsman’s block but he could never escape the ghosts of his conscience’. The film’s focus on the Tower of London as a symbol of ‘the corruption of the soul’ links the picture to the archetypes explored in Corman’s Gothic films, in particular the representation of Roderick Usher’s house as a symbol of Usher’s soul in The Fall of the House of Usher (Corman, 1960). The visits upon Richard by ghosts of those whose lives have been sacrificed to his ambition, and the ambiguity that surrounds these visitations (are they real, or are they a product of Richard’s paranoia?), also connects Tower of London to Corman’s horror films, as does the sequence in which Tyrus (Richard Hale) attempts to ‘call out’ these ‘evil spirits’ via the enactment of a paganistic rite.

The film also treads into territory covered by Corman’s Gothic adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories via its emphasis on acts of torture committed within the dungeons of the Tower of London. Richard attempts to persuade Mistress Shore to suggest that the young princes were fathered by someone other than Edward IV, telling Shore ‘With your help […] the birthright of the princes could be easily discredited’. However, Shore refuses and Richard has her taken to ‘the great persuader’ below: this ‘great persuader’ is of course the dungeon and the instruments of torture that are present within it. Richard later visits Shore in the dungeons and sees that she has been whipped (the camera lingers on the wounds on her exposed back), suggesting that ‘Perhaps a taste of the rack would be more to the lady’s liking’. When Shore protests ‘What manner of man are you that you could live with such evil on your conscience?’, Richard responds by simply laughing. In a later sequence, Richard has one of the conspirators against him tortured by having a cage strapped to the man’s face and a rat dropped into it: ‘While you are being entertained by your hungry guest, I shall be crowned’, Richard gloats. Here, Price’s performance as Richard is allied with his role as Nicholas Medina, the son of an agent of the Spanish Inquisition who revives his father’s methods of torture, in Corman’s The Pit and the Pendulum (1961). The torture chamber sequences in Tower of London anticipate the emphasis on similar sequences in later modern Gothics such as Michael Armstrong’s Hexen bis aufs Blut gequält (Mark of the Devil, 1970), Jess Franco’s Il trono di fuoco (The Bloody Judge, 1970) and Mario Bava’s Gli orrori del castello di Norimberga (Baron Blood, 1972). The film also treads into territory covered by Corman’s Gothic adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories via its emphasis on acts of torture committed within the dungeons of the Tower of London. Richard attempts to persuade Mistress Shore to suggest that the young princes were fathered by someone other than Edward IV, telling Shore ‘With your help […] the birthright of the princes could be easily discredited’. However, Shore refuses and Richard has her taken to ‘the great persuader’ below: this ‘great persuader’ is of course the dungeon and the instruments of torture that are present within it. Richard later visits Shore in the dungeons and sees that she has been whipped (the camera lingers on the wounds on her exposed back), suggesting that ‘Perhaps a taste of the rack would be more to the lady’s liking’. When Shore protests ‘What manner of man are you that you could live with such evil on your conscience?’, Richard responds by simply laughing. In a later sequence, Richard has one of the conspirators against him tortured by having a cage strapped to the man’s face and a rat dropped into it: ‘While you are being entertained by your hungry guest, I shall be crowned’, Richard gloats. Here, Price’s performance as Richard is allied with his role as Nicholas Medina, the son of an agent of the Spanish Inquisition who revives his father’s methods of torture, in Corman’s The Pit and the Pendulum (1961). The torture chamber sequences in Tower of London anticipate the emphasis on similar sequences in later modern Gothics such as Michael Armstrong’s Hexen bis aufs Blut gequält (Mark of the Devil, 1970), Jess Franco’s Il trono di fuoco (The Bloody Judge, 1970) and Mario Bava’s Gli orrori del castello di Norimberga (Baron Blood, 1972).

As Tower of London begins, Richard is regarded by Edward IV as a positive influence on both himself and the country: in the film’s opening sequence, Edward IV tells his son of the turmoil that exists within England during the era of the War of the Roses (‘I leave you a land filled with trouble’) before turning to Richard and asserting, ‘England has been cursed by wars, Richard, and you have been my right arm’. However, Richard is quick to exhibit jealousy when Clarence is named by Edward as Protector of the Realm. This incident sparks Richard’s subsequent cruel behaviour, driven by blind ambition; Richard’s ambition is described at one point in the film’s dialogue as ‘an ocean which cannot be held back’. As Tower of London begins, Richard is regarded by Edward IV as a positive influence on both himself and the country: in the film’s opening sequence, Edward IV tells his son of the turmoil that exists within England during the era of the War of the Roses (‘I leave you a land filled with trouble’) before turning to Richard and asserting, ‘England has been cursed by wars, Richard, and you have been my right arm’. However, Richard is quick to exhibit jealousy when Clarence is named by Edward as Protector of the Realm. This incident sparks Richard’s subsequent cruel behaviour, driven by blind ambition; Richard’s ambition is described at one point in the film’s dialogue as ‘an ocean which cannot be held back’.

However, Richard’s association with violence is signposted from very early in the story. ‘There are many who think you the wisest man in England’, George flatters Richard as they talk privately. ‘When we were children, there was no such thing as death’, Richard reflects, ‘We were three brothers who would exist forever’. ‘The years haven’t changed you, Richard’, George asserts, ‘Even as a child you thrilled to the swords, the lances, the heat of combat. To you, a battlefield possessed a grand sounding name only. It was not a field where men had cruelly shed their blood’. Shortly afterwards, Richard sinks his dagger into George’s back as George embraces him; Richard deflects responsibility for his act of malice, telling George ‘Don’t blame me […]; blame Edward’s choice’. He then dumps his brother’s body into a vat of wine before plotting to lay the blame for George’s murder at the doorstep of the House of Lancaster.  Though not a direct adaptation of Shakespeare’s play Richard III, the film gives Vincent Price ample opportunity to play a Shakespearian role, and there’s often a clear sense of delight in Price’s performance – such as when, following the murder of Clarence, Richard ascends to the battlements of the tower, launching into a monologue in which he questions ‘Is it what men do that darkens the sky, or do the skies blacken the souls of men? And do I laugh to myself because I am ambitious and would be king, or do I laugh at myself, a misshapen thing that traffics in evil to gain a throne?’ Though not a direct adaptation of Shakespeare’s play Richard III, the film gives Vincent Price ample opportunity to play a Shakespearian role, and there’s often a clear sense of delight in Price’s performance – such as when, following the murder of Clarence, Richard ascends to the battlements of the tower, launching into a monologue in which he questions ‘Is it what men do that darkens the sky, or do the skies blacken the souls of men? And do I laugh to myself because I am ambitious and would be king, or do I laugh at myself, a misshapen thing that traffics in evil to gain a throne?’

Here, as in the popular perception of Richard III, Richard’s actions are explained as both a product of his ambition and the bitterness he feels towards his disability and how this has led Richard to be treated by those around him. When Richard’s mother confronts him with the suggestion that he murdered his own brother, George, she suggests that ‘I brought this curse upon this house when my womb conceived you. Better I should have died at my labour and never unleashed your evil upon this earth’. Richard responds by angrily asserting, ‘You talk of evil? You, who gave me deformity in a twisted spine and a withered arm? Who possesses the greater evil, my mother, you who made me this way or I who have to bear it?’ In a number of sequences, it’s clear that Price clearly relished playing Richard III, in one scene vainly checking his fingernails whilst threatening violence against the Archbishop whilst asserting that his men will enter Westminster Abbey to take Elizabeth Woodville, who has sought sanctuary there, by force.  Price would later portray Richard III on screen again as part of his role in Douglas Hickox’s Theatre of Blood (1973), in which Price plays an actor, Edward Lionheart, who silences his critics by murdering them in baroque enactments of passages from Shakespeare’s plays. In one sequence, Lionheart re-enacts the murder of Clarence from Shakespeare’s Richard III, dumping the body of his victim in a vat of wine. Price would later portray Richard III on screen again as part of his role in Douglas Hickox’s Theatre of Blood (1973), in which Price plays an actor, Edward Lionheart, who silences his critics by murdering them in baroque enactments of passages from Shakespeare’s plays. In one sequence, Lionheart re-enacts the murder of Clarence from Shakespeare’s Richard III, dumping the body of his victim in a vat of wine.

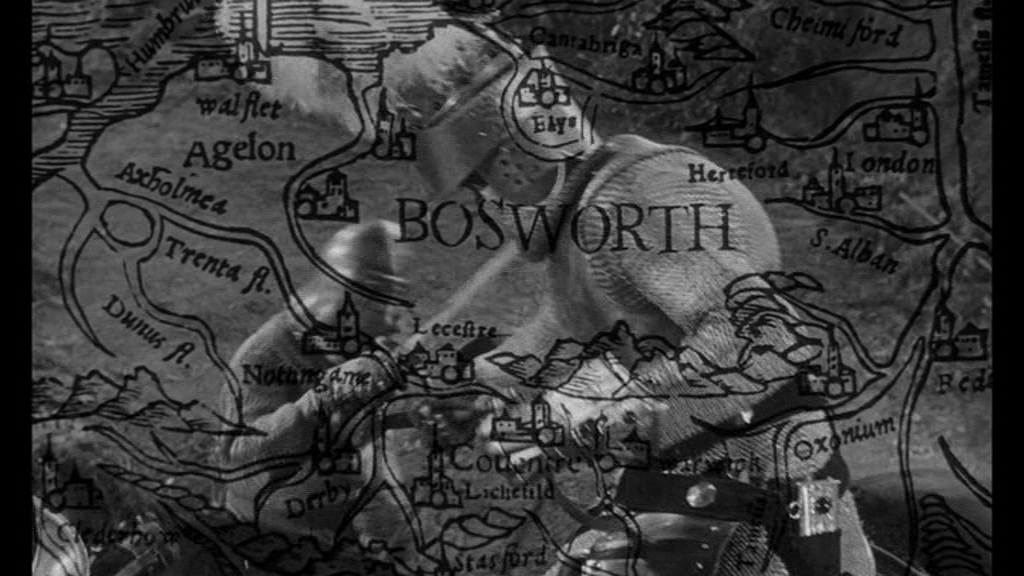

Corman was dissatisfied with Tower of London, however, once referring to the picture as ‘the most foolish thing I’ve ever filmed’ (Corman, quoted in Tavernier et al, 1964: 17). The film was one of three pictures that Corman was contracted to direct for producer Eddie Small, and Corman has said that the script for the film ‘was changed, reworked without my consent’ (Corman, quoted in ibid.). Additionally, Small insisted Corman shoot the picture in monochrome, and Corman wanted to make the film on colour stock. Angered at this interference in his film, Corman asked Eddie Small to tear up the contract binding Corman to the producer; Small consented (ibid.). Certainly, the limitations of the film’s $200,000 budget (less than half the budget of the 1939 film) are evident in a number of sequences: for example, in a cost-cutting measure designed to maximise the potential of the film’s meagre budget, Corman’s Tower of London elided the expense of staging the Battle of Bosworth by incorporating footage from the battle sequence shot for the 1939 picture and superimposing it over a map identifying the location.

Video

Please note that for the purposes of this review, we were only presented with DVD copies of the finished product and did not have access to the Blu-ray discs.  The film is presented in the 1.66:1 aspect ratio, with anamorphic enhancement on the DVD provided for review. The 35mm monochrome photography looks quite handsome here, with good contrast levels resulting in strong, defined midtones. However, blacks are often ‘crushed’, but of course without access to the Blu-ray disc, it’s impossible to say whether or not the HD presentation on the Blu-ray fares any better. The image is crisp and clear with a good level of detail and the natural structure of 35mm film retained within the presentation. There are some black flecks and specks within the image which suggest debris on a positive rather than negative source; the promotional materials identify the source for this presentation as being ‘transferred from original film elements by MGM’ but don’t clarify what ‘film elements’ these were. (I’d guess it was a fine grain positive print or something along those lines.) Some digital sharpening seems to have been conducted, but without access to the HD presentation on the Blu-ray it’s difficult to ascertain to what extent. The film is presented in the 1.66:1 aspect ratio, with anamorphic enhancement on the DVD provided for review. The 35mm monochrome photography looks quite handsome here, with good contrast levels resulting in strong, defined midtones. However, blacks are often ‘crushed’, but of course without access to the Blu-ray disc, it’s impossible to say whether or not the HD presentation on the Blu-ray fares any better. The image is crisp and clear with a good level of detail and the natural structure of 35mm film retained within the presentation. There are some black flecks and specks within the image which suggest debris on a positive rather than negative source; the promotional materials identify the source for this presentation as being ‘transferred from original film elements by MGM’ but don’t clarify what ‘film elements’ these were. (I’d guess it was a fine grain positive print or something along those lines.) Some digital sharpening seems to have been conducted, but without access to the HD presentation on the Blu-ray it’s difficult to ascertain to what extent.

The film runs for 76:34 mins (PAL) on the DVD disc provided for review. There are a handful of moments where the film appears to have suffered cuts, presumably made prior to its original distribution; as might be expected, these are located within the sequences that take place in the dungeons where Richard’s victims are tortured. For example, in the aforementioned scene in which Richard has a cage containing a rat strapped to the face of one of his enemies, there is an abrupt edit in the music and a clumsy cut to the next scene which suggests some footage has been removed from the final edit of the picture. Though it received an ‘X’ certificate, the film was originally cut by the BBFC when submitted for classification in 1962; these cuts were presumably to the torture chamber sequences too. The BBFC website logs the running time of the film on its original 1962 submission, pre-cuts, as 79:51 mins, which when converted to PAL comes out at around 76:38 mins; this would suggest the version of the film presented here is commensurate with that submitted to the BBFC in 1962.

Audio

Audio is presented via a single channel mono track. This is clean and clear, with dialogue audible throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are accurate and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with David Del Valle and Tara Gordon. In this commentary, film historian David Del Valle talks with the daughter of screenwriter Leo Gordon, who wrote this film. The commentary track is superb, filled with information about the film and Corman’s pictures in general. The commentators discuss the fact that both Corman and Price wanted the film to be shot in colour and were dismayed to discover that the producer had decided it be shot on monochrome stock. They also talk about the connections between this film and Price’s later performance in Theatre of Blood. It’s an excellent commentary track, and the commentators are warm, well-informed and personable. - Interview with Roger Corman (6:54). In a short interview, Corman reflects on the film’s genesis and production. Corman says the decision to shoot the film in monochrome was owing to the studio’s belief that this would save money when it came time to strike release prints; Corman says this was wrong-headed but concedes that the photography within the film is very good indeed. ‘I would say that Shakespeare, on balance, was a little better than Leo [Gordon] – but Leo was a fine writer in his own right’, Corman offers in reference to the script. - Interview with Gene Corman (13:30). Roger Corman and his brother Gene comment on Tower of London, Gene suggesting the picture was ‘a natural wedding of my abilities and his abilities’. The brothers Corman discuss the context in which the film was made and how it came to be produced. - Slideshow (4:20). This is a slideshow of promotional materials from the film’s original release.

Overall

Rewatching Tower of London and its fusion of historical events and exploitation – much like many of the witchhunting films that would become popular at the end of the decade, following Michael Reeves’ Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (1968) – it’s difficult not to reflect on current popular trends in television programme which mix allusions to history with fantastical narratives and exploitation cinema-like sensibilities. An obvious point of comparison here is the popular HBO series Game of Thrones (2011- ), which has often alluded to both the War of the Roses and Shakespeare’s texts. Corman’s take on the story of Richard III is curiously similar in sensibility to Game of Thrones, though not quite as graphic. Tower of London is by all accounts a footnote in the Corman-Price collaborations, but even though the limitations of the budget are all too noticeable (in the pilfered footage of the Battle of Bosworth and the deplorable miniature shots) it’s an enjoyable little film – and the story of Richard III has seemingly universal relevance. Arrow’s new release of the film contains a solid presentation and some good contextual material, especially the commentary with David Del Valle and Tara Gordon. Rewatching Tower of London and its fusion of historical events and exploitation – much like many of the witchhunting films that would become popular at the end of the decade, following Michael Reeves’ Matthew Hopkins: Witchfinder General (1968) – it’s difficult not to reflect on current popular trends in television programme which mix allusions to history with fantastical narratives and exploitation cinema-like sensibilities. An obvious point of comparison here is the popular HBO series Game of Thrones (2011- ), which has often alluded to both the War of the Roses and Shakespeare’s texts. Corman’s take on the story of Richard III is curiously similar in sensibility to Game of Thrones, though not quite as graphic. Tower of London is by all accounts a footnote in the Corman-Price collaborations, but even though the limitations of the budget are all too noticeable (in the pilfered footage of the Battle of Bosworth and the deplorable miniature shots) it’s an enjoyable little film – and the story of Richard III has seemingly universal relevance. Arrow’s new release of the film contains a solid presentation and some good contextual material, especially the commentary with David Del Valle and Tara Gordon.

References: Tavernier, Bertrand et al, 1964: ‘Corman Speaks’. In: Nasr, Constantine (ed), 2011: Roger Corman: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi

|

|||||

|