|

|

Willie Dynamite (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (12th February 2017). |

|

The Film

Willie Dynamite (Gilbert Moses, 1974) Willie Dynamite (Gilbert Moses, 1974)

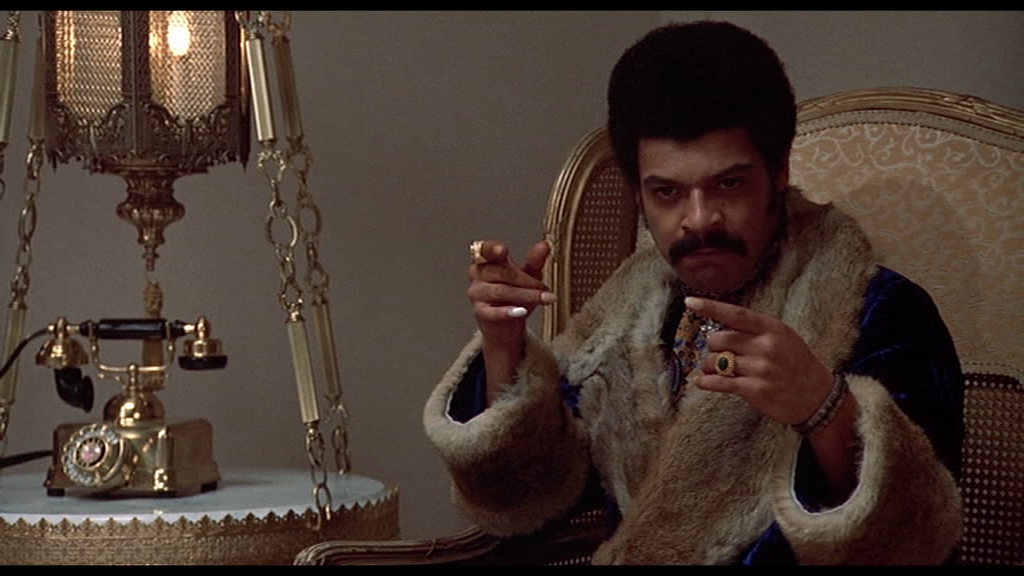

Though many of the blaxploitation pictures made during the 1970s were directed by predominantly white crews and helmed by white directors (such as Jack Hill, Jack Starrett and Larry Cohen), a handful of these films were made by black filmmakers; Gilbert Moses III, the director of Willie Dynamite (1974), was one such director, as was Melvin Van Peebles (the director of Sweet Sweetback’s Badassss Song!, 1971), D’Urville Martin (Dolemite, 1975) and both Gordon Parks (Shaft, 1971) and his son Gordon Parks Jr (Super Fly, 1972). What distinguished Shaft from many of the blaxploitation films that followed, regardless of the background of their directors, was the worldview brought to the film by Gordon Parks, whose long-standing experience as a social documentary photographer (originally with the Farm Security Administration, and later during the Civil Rights era), shone through in his depiction of New York City life and the interactions between different social groups: Parks knew poverty and life on the street intimately, and it is this world-weariness that makes Shaft such a potent film. In contrast with Parks, Gilbert Moses III’s background was in theatre, and though Willie Dynamite begins as high camp, in its final sequences it moves into a very similar, grounded depiction of city life to that which is evidenced in Parks’ film. Willie Dynamite offers a darkly comic, deeply ironic satire of the stereotypes surrounding black culture and its representation in Hollywood cinema. Moses directed Willie Dynamite after being flown to LA by Universal in 1972; having been impressed with his track record in the world of theatre, the studio wanted to assess Moses’ feelings regarding pursuing a career as a director of films (see Corson, 2016: 145). Moses was hired to direct a picture called ‘Eli’s Game’, but the project was cancelled by Universal before the film went into production (ibid.). Following this, Moses returned to New York and was offered Willie Dynamite, again by Universal. Keith Corson notes that the film’s one million dollar budget was ‘sizable’ in comparison with the budgets of most blaxploitation films, and Willie Dynamite was ‘one of the rare blaxploitation films both fully financed and distributed by a major studio’ (ibid.). Universal’s aim was to capture some of the audience share of popular, recent blaxploitation pictures such as Shaft and Super Fly.  The film focuses on Willie Dynamite (Roscoe Orman), a flashy pimp who runs a ‘stable’ of prostitutes in New York City. Willie’s girls sell their services at hotels where businessmen gather for conventions. However, Willie faces competition from the city’s other pimps, and at one of their regular meetings Willie is confronted by rival pimp Bell (Roger Robinson). Bell argues that the city’s pimps should organise and divide up turf amongst themselves. Willie, a true capitalist, resists this angrily. The film focuses on Willie Dynamite (Roscoe Orman), a flashy pimp who runs a ‘stable’ of prostitutes in New York City. Willie’s girls sell their services at hotels where businessmen gather for conventions. However, Willie faces competition from the city’s other pimps, and at one of their regular meetings Willie is confronted by rival pimp Bell (Roger Robinson). Bell argues that the city’s pimps should organise and divide up turf amongst themselves. Willie, a true capitalist, resists this angrily.

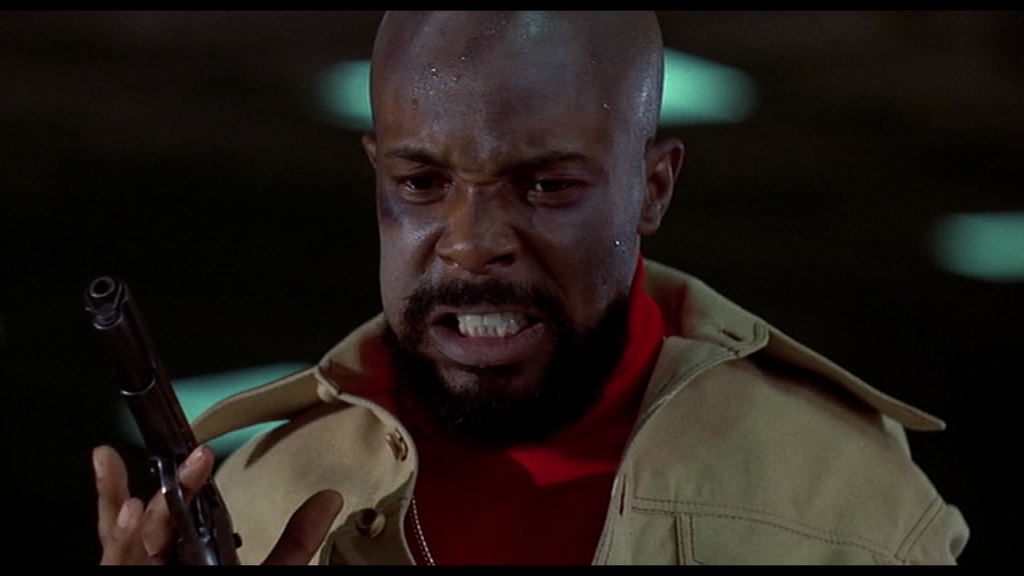

When one of Willie’s newest girls, Pashen (Joyce Walker), is arrested, she comes into contact with prostitute-turned-social worker Cora (Diana Sands). Telling Pashen she ‘could have a real life without busts and horrorshow johns’, Cora attempts to get Pashen to turn against Willie. After Willie has treated his girls violently, Cora gains entry into his offices and speaks with his ‘stable’, telling them they are ‘the saddest, ripped-off bitches I’ve ever known’. She advises them to go freelance: ‘Organise’, she tells them, ‘You don’t need Willie. Don’t you know, we’re liberated now’. Willie is arrested on a bizarre charge of stealing a hundred dollars from a Puerto Rican grocer, and in the police station he meets Pointer (Albert Hall), a black Muslim detective, and his Italian-American partner Celli (George Murdock). Meanwhile, Cora closes in on Willie. Where Willie plans to be ‘number one’, Cora aims to make him ‘number one minus one, which equals zero’. Cora tightens the screws on Pashen, despite open threats from Willie. Willie also finds his business interests, and his own life, under threat from Bell, who holds Willie at gunpoint before Willie turns the tables and leaves Bell, stripped naked, by the roadside.  Willie’s girls are attacked by another group of prostitutes at a hotel where they are plying their trade, and Willie’s ‘bottom lady’ has her throat slit by a rival. Amidst this, the police and the IRS begin to close in on Willie and it seems that like Al Capone, Willie will be tried for income tax evasion. Finally, Bell catches up to Willie and beats him viciously; Willie returns home, his face a bloody mess, only to encounter Pointer and Celli there. The two detectives arrest Willie for possession of narcotics and carrying a concealed weapon. Willie’s girls are attacked by another group of prostitutes at a hotel where they are plying their trade, and Willie’s ‘bottom lady’ has her throat slit by a rival. Amidst this, the police and the IRS begin to close in on Willie and it seems that like Al Capone, Willie will be tried for income tax evasion. Finally, Bell catches up to Willie and beats him viciously; Willie returns home, his face a bloody mess, only to encounter Pointer and Celli there. The two detectives arrest Willie for possession of narcotics and carrying a concealed weapon.

Having got through to Pashen and sent her off to her family in Boston, Cora confronts Willie and tells him that his elderly mother, who until recently has had no idea as to Willie’s true occupation, is seriously ill in hospital. Stripped of the symbols of his lavish lifestyle and retreating to a very proletarian apartment in an equally proletarian neighbourhood, Willie is ultimately forced to confront his alienation from those around him and eradicate his own ego. Many of the blaxploitation films of the early/mid-1970s featured film noir-style themes and narratives, something which has been discussed at length by Dan Flory in the book Philosophy, Black Film, Film Noir (2008: 37). Aside from the obvious similarities in the emphasis in both films noir and blaxploitation pictures on crime in an urban milieu, Flory argues that the 1970s blaxploitation films often ‘use[d] the techniques and themes of noir to tap into audience sympathies for violent, “bad” black male and female characters’ (ibid.). With its focus on Richard Roundtree’s black private investigator John Shaft, Shaft is often credited as kickstarting the blaxploitation cycle; certainly the films that followed can be divided into those which feature characters on the side of the law (such as Shaft, whose protagonist is a private detective) and those who are criminals (such as Super Fly and Dolemite, whose anti-heroes are a cocaine dealer and a pimp, respectively). This, again, is a similarity between the blaxploitation era and classic films noir, which were just as likely to feature a criminal as their protagonist (for example, Victor Mature’s ex-con protagonist in Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death, 1947) as policemen or private investigators (eg, Humphrey Bogart’s performance as Sam Spade in John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon, 1941)  Arguably, the ‘point’ of both many films noir and blaxploitation pictures was to show the thin line between ‘acceptable’ and ‘deviant’ behaviour, and narrativise how an individual can cross from one side to the other without necessarily making a conscious decision to do this: for example, Dana Andrews’ character in Where the Sidewalk Ends (Otto Preminger, 1950), or Richard Roundtree’s John Shaft, both of whom begin their stories as investigators of crimes but find themselves transgressing the law. This is perhaps the overriding theme of Willie Dynamite, though the movement is in reverse to the aforementioned films: the first hour or so depicts Willie D’s life of criminality, arrogance and excess – his pimping and abuse of the women in his ‘stable’ – and the last half hour focuses on how he is humbled by the actions of both the police and Diana Sands’ social worker, catalysed by the death of his mother, to the point that he happily sacrifices his world of riches in exchange for a modest proletarian existence. It’s a riches-to-rags fable that begins as high camp but resolves itself in a series of sequences that feel as if Gilbert Moses III somehow channeled the spirit of Charles Dickens, transplanting Dickens’ social conscience from Victorian London to 1970s New York City. Arguably, the ‘point’ of both many films noir and blaxploitation pictures was to show the thin line between ‘acceptable’ and ‘deviant’ behaviour, and narrativise how an individual can cross from one side to the other without necessarily making a conscious decision to do this: for example, Dana Andrews’ character in Where the Sidewalk Ends (Otto Preminger, 1950), or Richard Roundtree’s John Shaft, both of whom begin their stories as investigators of crimes but find themselves transgressing the law. This is perhaps the overriding theme of Willie Dynamite, though the movement is in reverse to the aforementioned films: the first hour or so depicts Willie D’s life of criminality, arrogance and excess – his pimping and abuse of the women in his ‘stable’ – and the last half hour focuses on how he is humbled by the actions of both the police and Diana Sands’ social worker, catalysed by the death of his mother, to the point that he happily sacrifices his world of riches in exchange for a modest proletarian existence. It’s a riches-to-rags fable that begins as high camp but resolves itself in a series of sequences that feel as if Gilbert Moses III somehow channeled the spirit of Charles Dickens, transplanting Dickens’ social conscience from Victorian London to 1970s New York City.

Near the end of the film, his mother dying in hospital and Willie having been stripped of the trappings of his life as a pimp, a downtrodden Willie walks through the city streets, his memories of his previous lifestyle intercut with the increasing sense of connection he feels within his environment during his drifting movement through the working class neighbourhood. The epiphany comes when Willie sees the purple Cadillac that, earlier, he was so protective about. The car is being towed away. A young boy approaches Willie: ‘Hey, mister, that your car they’re towing?’, the boy asks. ‘No’, Willie replies, smiling, ‘Not anymore’. These final sequences give the film the structure and potency of a moral fable, counteracting the camp excesses of the film’s opening hour – especially Roger Robinson’s manic performance as Bell, the pimp who tries to insists the other pimps ‘collectivise or run’ (‘I respect your ambition, Willie, but you got to have vizzzionnnn!’).  As Willie D, Roscoe Orman encapsulates the stereotype of the 1970s NYC pimp that many viewers will likely think of when blaxploitation films are mentioned. Clad in his white, brown-striped lambskin hat and coat (Willie D takes great offence when people don’t recognise the symbolism of wealth associated with this garment – ‘A brown coat? This is lamb! I paid over a grand for it’, he protests), he drives a purple Cadillac with leopard skin seats. The iconography is so loud and brash that it was parodied for decades afterwards and is still instantly recognisable today. When, in the 1996 episode of Seinfeld entitled ‘The Wig Master’, Cosmo Kramer steps out onto the streets of New York in the coat from Joseph and His Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and matches this with a cane and outrageous hat before being mistaken for a pimp, the show’s producers may very well have been alluding directly to Willie D’s get-up in this film. As Willie D, Roscoe Orman encapsulates the stereotype of the 1970s NYC pimp that many viewers will likely think of when blaxploitation films are mentioned. Clad in his white, brown-striped lambskin hat and coat (Willie D takes great offence when people don’t recognise the symbolism of wealth associated with this garment – ‘A brown coat? This is lamb! I paid over a grand for it’, he protests), he drives a purple Cadillac with leopard skin seats. The iconography is so loud and brash that it was parodied for decades afterwards and is still instantly recognisable today. When, in the 1996 episode of Seinfeld entitled ‘The Wig Master’, Cosmo Kramer steps out onto the streets of New York in the coat from Joseph and His Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and matches this with a cane and outrageous hat before being mistaken for a pimp, the show’s producers may very well have been alluding directly to Willie D’s get-up in this film.

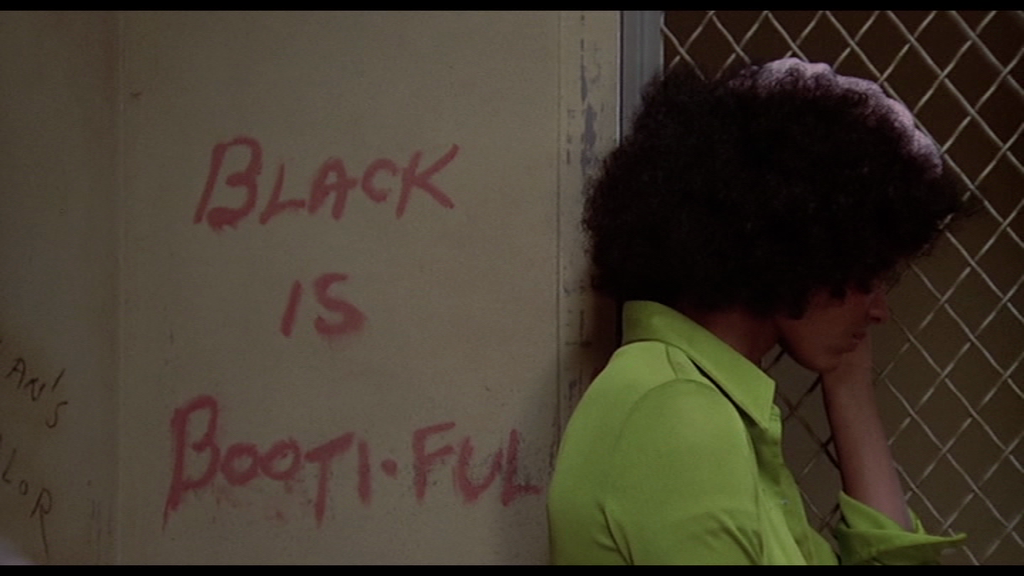

Though for the first hour of the film, Willie D is little more than a caricature who embodies the negative stereotypes about black men that have been propagated in Hollywood cinema – driving around the city in his flashy Cadillac, treating his ‘bitches’ cruelly and demonstrating a jarringly Ted Bundy-esque way of speaking of himself in the third person – towards the end of the picture this aspect of his character is juxtaposed with another. Midway through the film, Moses presents us with a scene of Willie visiting his family, who are unaware of his true occupation and believe him to be a musician. Suddenly, Willie’s arrogance disappears and he speaks humbly and respectfully. The scene is filled with irony and double entendres. ‘I’d like to see him [Willie] in action’, his mother asserts before asking after his business. ‘It’s up and down’, Willie responds. As the film progresses, Willie’s family – and especially his ailing mother – play an increasingly important role, necessitating a confrontation within Willie between how he has presented himself to others in his role as a pimp, and what his family believe him to be.  Keith Corson suggests that Willie Dynamite is ‘less a straightforward tale of the hustler’s life than it is a nuanced satire of Hollywood’s conception of black life’ (op cit.: 146). Corson points to the film’s opening credits sequence, in which Martha Reeves’ superb main title theme song plays out over night-time shots of Willie D driving his purple Cadillac through the city streets: ‘Willie drives through Manhattan in his Cadillac Eldorado’, Corson writes, ‘passing by a Times Square marquee reading “Pornography in Hollywood.” It’s a self-aware nod that recognizes Willie Dynamite is a part of the blaxploitation cycle and signifies the film’s stereotyped black masculinity is intentional’ (ibid.). At the end of the film, a transformed, socially-conscious Willie – stripped of the trappings of wealth, criminality and vulgar taste with which he was associated in the film’s early sequences – walks past a book store: ‘Framed between a theater marquee and a bookstore sign’, Corson notes, ‘Willie’s experiences follow a broader commentary on the debilitating fantasies of blaxploitation and the need to invest in education’ (ibid.). Keith Corson suggests that Willie Dynamite is ‘less a straightforward tale of the hustler’s life than it is a nuanced satire of Hollywood’s conception of black life’ (op cit.: 146). Corson points to the film’s opening credits sequence, in which Martha Reeves’ superb main title theme song plays out over night-time shots of Willie D driving his purple Cadillac through the city streets: ‘Willie drives through Manhattan in his Cadillac Eldorado’, Corson writes, ‘passing by a Times Square marquee reading “Pornography in Hollywood.” It’s a self-aware nod that recognizes Willie Dynamite is a part of the blaxploitation cycle and signifies the film’s stereotyped black masculinity is intentional’ (ibid.). At the end of the film, a transformed, socially-conscious Willie – stripped of the trappings of wealth, criminality and vulgar taste with which he was associated in the film’s early sequences – walks past a book store: ‘Framed between a theater marquee and a bookstore sign’, Corson notes, ‘Willie’s experiences follow a broader commentary on the debilitating fantasies of blaxploitation and the need to invest in education’ (ibid.).

Corson highlights the film’s moments of camp excess, especially Roger Robinson’s performance. Corson argues that Moses’ intent was to satirise the blaxploitation form – or, perhaps more accurately, the audience’s expectations of blaxploitation films. For Corson, Moses ‘codes his sense of irony for the knowing spectator’ (op cit.: 146). Robinson’s performance as Bell, for example (‘You sayin’ you can’t control your bitches?’, Bell accusingly asks Willie D at one point in the film), ‘is an outright send-up of the caricatures populating other blaxploitation films’ (ibid.). This has the effect of ‘undercutting any romantic notion of the player lifestyle by making it appear wholly ridiculous’ (ibid.). Credibility is intentionally pushed ‘to the edge’, with Moses ‘seeing how far he can take the humor without it crossing over into transparent parody’ (ibid.). This attempt to push the film’s comic moments into sheer outrageousness, right to the point at which it becomes obvious how satirical Moses’ intentions are, is emblematised in two scenes in particular. Late in the film, Willie D invades Cora’s office and Cora telephones the police, telling them that an intruder is preparing to rape both Cora and her assistant. Willie responds by making a joke that will make even the most broad-minded viewer wince: ‘Rape you? [….] I’d rather rape a watermelon’, he says. The moment makes explicit Moses’ dry, ironic satire, openly assaulting Hollywood’s decades-long perpetuation of negative stereotypes about African American culture and, especially, African American males. The earlier scene in which Bell engages the other pimps in a dialogue about collectivisation and the dividing up of territory plays on a camp, ironic and satirical appropriation of the stereotypes of black, urban life that populate many blaxploitation films of the 1970s whilst also incorporating a dialogue about economics and business that ‘provide[s] the primary social critique of the film’ (ibid.). By doing this, Moses ‘locat[es] the crux of the film in his funniest scene’ (ibid.).  In the board meeting of pimps, Willie D and Bell become involved in an almost didactic disagreement over the nature of their business as pimps. Bell argues that in order to escape attention from the police, the pimps need to collectivise and divide up territory, agreeing which of them will control which ‘turf’; Willie D, on the other hand, believes in a totally free market, welcoming competition and believing that the pimp with the best ‘stable’ will win out. (Interestingly, Willie D’s ‘stable’ of prostitutes is multi-ethnic; referring back to the film’s emphasis on pimping as a metaphor for big business, one might say that Willie D comprehends the importance of diversification of product within the marketplace.) ‘The heat [… is] comin’ down hard’, Bell asserts, ‘We gotta get our shit together […] No other business is run so disorganized [….] The action’s goin’ to get scarce and times is goin’ to get hard’. When Bell proposes the pimps divide the city into different territories, Willie resists. ‘Man, I thought we was all capitalists’, Willie asserts, ‘Free enterprise, you dig?’ ‘I run every kind of bitch in every kind of place, but I know one thing’, Bell responds, ‘when it comes down on you, you either collectivise or you run like a solitary rat’. ‘I like the competition’, Willie declares, ‘and I can deal with any heat […] I’m controllin’ some tough, aggressive, mean-lookin’ animals and I’m gonna tell them they can only run in one part of the jungle?’ In the board meeting of pimps, Willie D and Bell become involved in an almost didactic disagreement over the nature of their business as pimps. Bell argues that in order to escape attention from the police, the pimps need to collectivise and divide up territory, agreeing which of them will control which ‘turf’; Willie D, on the other hand, believes in a totally free market, welcoming competition and believing that the pimp with the best ‘stable’ will win out. (Interestingly, Willie D’s ‘stable’ of prostitutes is multi-ethnic; referring back to the film’s emphasis on pimping as a metaphor for big business, one might say that Willie D comprehends the importance of diversification of product within the marketplace.) ‘The heat [… is] comin’ down hard’, Bell asserts, ‘We gotta get our shit together […] No other business is run so disorganized [….] The action’s goin’ to get scarce and times is goin’ to get hard’. When Bell proposes the pimps divide the city into different territories, Willie resists. ‘Man, I thought we was all capitalists’, Willie asserts, ‘Free enterprise, you dig?’ ‘I run every kind of bitch in every kind of place, but I know one thing’, Bell responds, ‘when it comes down on you, you either collectivise or you run like a solitary rat’. ‘I like the competition’, Willie declares, ‘and I can deal with any heat […] I’m controllin’ some tough, aggressive, mean-lookin’ animals and I’m gonna tell them they can only run in one part of the jungle?’

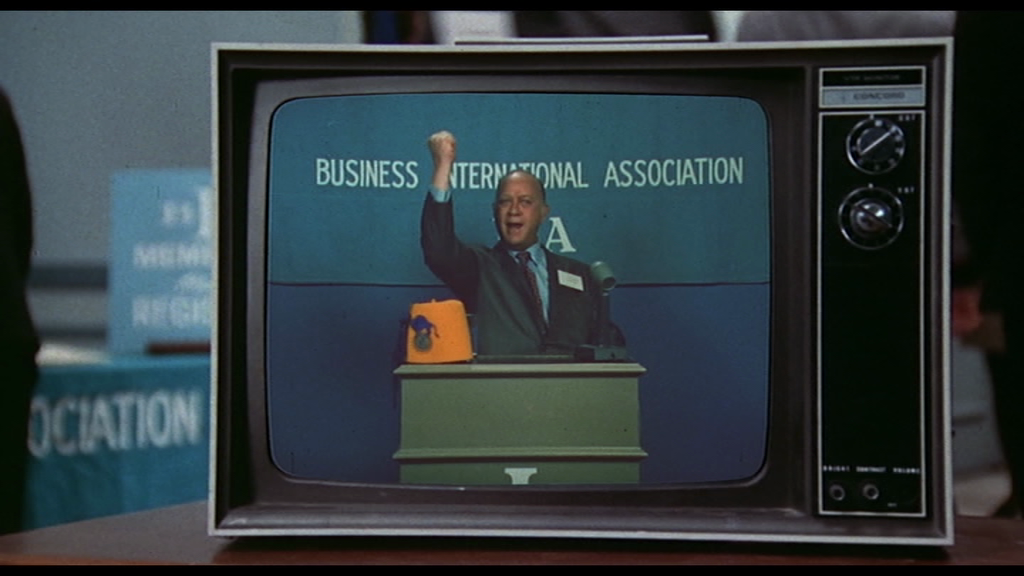

The scene underscores the parallels that the film has drawn between pimping and ‘legitimate’ business since its opening sequence. ‘Seven women in the palm of his hand / Willie D’, Martha Reeves sings over the opening titles, ‘Selling fantasies, whatever you please / It’s no different from any other industry’. As Willie’s prostitutes sidle up to a group of men who are in town for a convention, Moses cuts to a television monitor on which a man speaks about business: ‘Today, more than ever before, the operator of a small business must combine a set of rare abilities’, the man says, ‘The first is aggressiveness. Second, the ability to make instantaneous decisions and find a challenge in the face of adversity. Third, is the desire to surmount any obstacle, no matter how great or small’. As the speaker makes each point, Moses cuts to one of Willie’s ‘girls’ demonstrating such an ‘ability’ with her client: the commentator on the television identifies his third ‘ability’ over the image of one of Willie’s prostitutes seducing a middle-aged, fat and balding man. In a subsequent scene, Willie refers to his girls explicitly as ‘the production line’: ‘This is a business, baby’, he advises Pashen, ‘A production line. And just like GM, Ford, Chrysler, Willie’s comin’ through [….] Willie’s sellin’ an idea. You’re not only burnin’ the chump’s body, you’re settin’ fire to his brain [….] You got to make him feel like he’s ballin’ the Statue of Liberty’. The scene underscores the parallels that the film has drawn between pimping and ‘legitimate’ business since its opening sequence. ‘Seven women in the palm of his hand / Willie D’, Martha Reeves sings over the opening titles, ‘Selling fantasies, whatever you please / It’s no different from any other industry’. As Willie’s prostitutes sidle up to a group of men who are in town for a convention, Moses cuts to a television monitor on which a man speaks about business: ‘Today, more than ever before, the operator of a small business must combine a set of rare abilities’, the man says, ‘The first is aggressiveness. Second, the ability to make instantaneous decisions and find a challenge in the face of adversity. Third, is the desire to surmount any obstacle, no matter how great or small’. As the speaker makes each point, Moses cuts to one of Willie’s ‘girls’ demonstrating such an ‘ability’ with her client: the commentator on the television identifies his third ‘ability’ over the image of one of Willie’s prostitutes seducing a middle-aged, fat and balding man. In a subsequent scene, Willie refers to his girls explicitly as ‘the production line’: ‘This is a business, baby’, he advises Pashen, ‘A production line. And just like GM, Ford, Chrysler, Willie’s comin’ through [….] Willie’s sellin’ an idea. You’re not only burnin’ the chump’s body, you’re settin’ fire to his brain [….] You got to make him feel like he’s ballin’ the Statue of Liberty’.

Aside from Bell, Willie D is also contrasted with Pointer, the black Muslim police detective. Where Willie D is aggressive, misogynistic, energetic and flashy, Pointer is uptight, morally righteous and restrained. Willie is an individualist, utterly selfish and motivated by his desire to be ‘number one’; Pointer, by contrast, is socially-minded and cognisant of the suffering of his peers. However, Pointer’s judgements are extreme: when, during his pursuit of Willie near the climax of the film, Pointer stumbles into an ailing junkie in the stairwell of an abandoned building, Pointer tells the man, ‘Maybe I should have shot you. They’d call it a mercy killing’. When Willie first meets Pointer, Pointer confronts the pimp over one of Willie’s prostitutes who died of an overdose the previous night. ‘You used her, body and soul’, Poiner asserts angrily. ‘Why all this concern over a dead junkie?’, Willie asks, ‘She your sister?’ ‘Yeah, she’s my sister’, Pointer responds, ‘Your sister too’. Willie tells Pointer and Celli that he is going to contact the NAACP over the treatment he has received at the hands of the police. ‘Son of a bitch memorised every one of those statutes’, Celli declares in reference to Willie’s familiarity with the law. ‘I just watch Ironside’, Willie quips.  Sadly, Willie Dynamite wasn’t the critical or financial success that Universal hoped for, and turned the studio away from making more blaxploitation films. Universal believed that the film’s lack of financial success spoke of ‘the limited prospects of black-focused film’ but this ‘was largely a self-fulfilling prophecy’ (Corson, op cit.: 148). The blaxploitation cycle proved itself to be short-lived, at least in its connections with Hollywood studios; the decline of the blaxploitation film also meant that opportunities for black filmmakers began to dry up (ibid.). Other than The Fish Who Saved Pittsburgh (Gilbert Moses, 1979), Moses never completed another feature film; the projects that he initiated were mostly halted at the pre-production stage, and Moses found work in television instead. Universal failed to stand behind Willie Dynamite, and without the studio’s support Willie Dynamite ‘fell victim to poor reviews from a white critical establishment that failed to make sense of the satire or locate the levels of social commentary’ (ibid.). Sadly, Willie Dynamite wasn’t the critical or financial success that Universal hoped for, and turned the studio away from making more blaxploitation films. Universal believed that the film’s lack of financial success spoke of ‘the limited prospects of black-focused film’ but this ‘was largely a self-fulfilling prophecy’ (Corson, op cit.: 148). The blaxploitation cycle proved itself to be short-lived, at least in its connections with Hollywood studios; the decline of the blaxploitation film also meant that opportunities for black filmmakers began to dry up (ibid.). Other than The Fish Who Saved Pittsburgh (Gilbert Moses, 1979), Moses never completed another feature film; the projects that he initiated were mostly halted at the pre-production stage, and Moses found work in television instead. Universal failed to stand behind Willie Dynamite, and without the studio’s support Willie Dynamite ‘fell victim to poor reviews from a white critical establishment that failed to make sense of the satire or locate the levels of social commentary’ (ibid.).

Video

Please note that for the purposes of this review, we were only presented with DVD copies of the finished product and did not have access to the Blu-ray discs. Please note that for the purposes of this review, we were only presented with DVD copies of the finished product and did not have access to the Blu-ray discs.

Willie Dynamite is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, with anamorphic enhancement on the DVD copy provided for review. The image is very rich and detailed, with excellent colour reproduction: the vivid, vulgar hues of Willie’s offices are communicated very nicely, as are the neon signs of Times Square during the film’s opening titles sequence. Contrast levels are good too, with nicely balanced midtones. The film also retains a natural, film-like appearance. The film is uncut, running for 97:47 mins (PAL).

Audio

Audio on this DVD copy is presented via a Dolby Digital 2.0 stereo track. This is rich and clear, dialogue and the superb funk soundtrack both being communicated very well. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are easy to read and accurate.

Extras

The DVD includes:  - Without Walls: ‘Kiss My Baad Assss—Ice T’s Guide to Blaxploitation’ (24:39). Originally broadcast on Channel 4 in 1994, as part of their ongoing Without Walls strand, this documentary was introduced and narrated by Ice-T. Ice-T looks back at the history of blaxploitation films, considering how African Americans were represented in early cinema before looking at how the blaxploitation era changed these paradigms of representation. The documentary features interviews with a number of key personnel associated with blaxploitation cinema, including Melvin Van Peebles, Isaac Hayes and writer Iceberg Slim. The interviews are interspersed with commentary from Ice-T and footage from the films. - Without Walls: ‘Kiss My Baad Assss—Ice T’s Guide to Blaxploitation’ (24:39). Originally broadcast on Channel 4 in 1994, as part of their ongoing Without Walls strand, this documentary was introduced and narrated by Ice-T. Ice-T looks back at the history of blaxploitation films, considering how African Americans were represented in early cinema before looking at how the blaxploitation era changed these paradigms of representation. The documentary features interviews with a number of key personnel associated with blaxploitation cinema, including Melvin Van Peebles, Isaac Hayes and writer Iceberg Slim. The interviews are interspersed with commentary from Ice-T and footage from the films.

I remember being fascinated with this documentary when it was first broadcast, and finding many of the films difficult – or nigh impossible – to view. Now, in the digital home video era, many of the key blaxploitation films are quite easy to access; but sadly, arts-themed documentaries such as this are few and far between on the television landscape. More’s the pity. In an ideal world, we’d have easy access to the films and fascinating documentaries such as this on television. - Trailer (1:57). Retail copies of the Blu-ray release will include a reversible sleeve option, and first pressings will include a booklet with a new piece of writing about the film by Julian Upton.

Overall

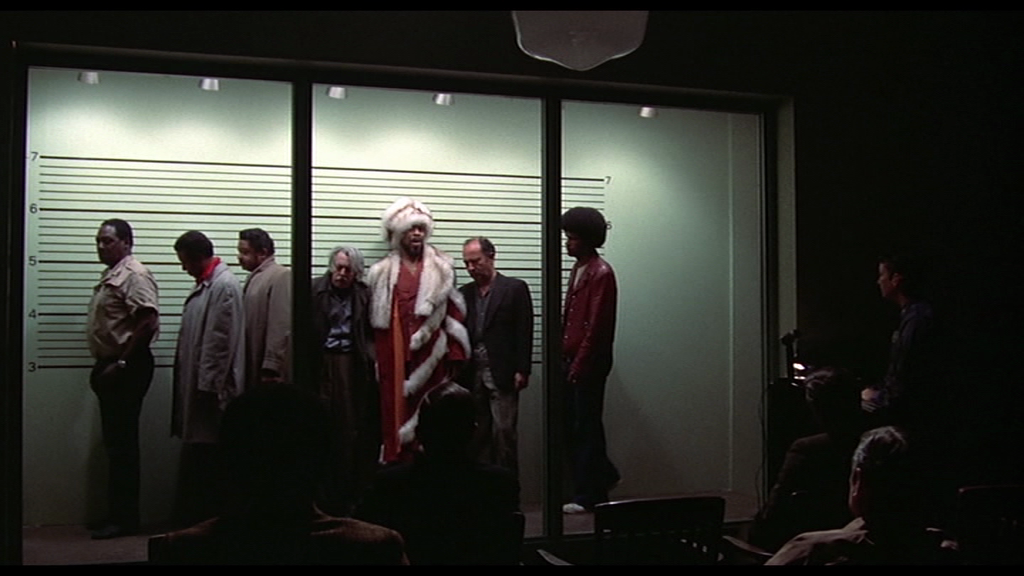

Filled with deliriously funny scenes (including Willie D, in his outrageous pimp attire, placed in a police line-up amongst regular citizens), Willie Dynamite is a deliciously satirical film. The first hour is characterised by camp excess and a regurgitation of stereotypes – but the attentive viewer gradually becomes increasingly aware of how ironic and subversive Moses’ appropriation of these stereotypes is. Then the final half hour or so, depicting Willie’s change of heart, is incredibly impactful and delivered by a barnstorming performance from Roscoe Orman. Filled with deliriously funny scenes (including Willie D, in his outrageous pimp attire, placed in a police line-up amongst regular citizens), Willie Dynamite is a deliciously satirical film. The first hour is characterised by camp excess and a regurgitation of stereotypes – but the attentive viewer gradually becomes increasingly aware of how ironic and subversive Moses’ appropriation of these stereotypes is. Then the final half hour or so, depicting Willie’s change of heart, is incredibly impactful and delivered by a barnstorming performance from Roscoe Orman.

Ultimately, the film is both a deeply moral fable and a subversive reflection on the stereotypes about African American culture that have been circulated within Hollywood cinema. Arrow’s release of the film is very good: though we were only presented with a DVD copy of the release for the purposes of this review, the presentation is pleasing and, although some more contextual material would have been helpful, the inclusion of Ice-T’s documentary about blaxploitation, made for Channel 4’s Without Walls strand, is very welcome: I hadn’t seen this since its first broadcast and had forgotten how good it was. Though obviously not the length of Isaac Julien’s BaadAsssss Cinema (2002), Ice-T’s short documentary features some fascinating interviews with some of the personnel involved in the blaxploitation era. On the whole, it’s a pleasing release of an often overlooked blaxploitation picture. References: Corson, Keith, 2016: Trying to Get Over: African American Directors After Blaxploitation, 1977-1986. University of Texas Press Flory, Dan, 2008: Philosophy, Black Film, Film Noir. Pennsylvania State University Press

|

|||||

|