|

|

Kiss of Death (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (24th July 2016). |

|

The Film

Kiss of Death (Henry Hathaway, 1947)  Beginning with a bravura jewellery heist that takes place in the Chrysler Building, Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947) focuses on lifelong loser Nick Bianco (Victor Mature), a member of the stick-up gang responsible for the heist. Raised in an orphanage, Nick found himself on the wrong side of the proverbial tracks from a young age; an ex-con with a record, a wife and two young daughters, Bianco feels that crime is the only option available to him. When Nick is injured by a policeman’s bullet whilst escaping from the heist in the Chrysler Building, he faces criminal charges and comes into contact with Assistant District Attorney Louis D’Angelo (Brian Donlevy). D’Angelo tries to convince Nick to ‘squeal’ on his associates in the heist, who escaped capture, with the promise of a more lenient sentence. However, Nick refuses to co-operate with D’Angelo and is thrown into Sing Sing Correctional Facility. There, he meets sadistic hoodlum Tommy Udo (Richard Widmark) – his love of violence signaled in his first conversation with Nick, in which Udo promises of one of the prison guards that ‘For a nickel, I’d grab him. Stick both thumbs right in his eyes; hang on till he drops dead’. Beginning with a bravura jewellery heist that takes place in the Chrysler Building, Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947) focuses on lifelong loser Nick Bianco (Victor Mature), a member of the stick-up gang responsible for the heist. Raised in an orphanage, Nick found himself on the wrong side of the proverbial tracks from a young age; an ex-con with a record, a wife and two young daughters, Bianco feels that crime is the only option available to him. When Nick is injured by a policeman’s bullet whilst escaping from the heist in the Chrysler Building, he faces criminal charges and comes into contact with Assistant District Attorney Louis D’Angelo (Brian Donlevy). D’Angelo tries to convince Nick to ‘squeal’ on his associates in the heist, who escaped capture, with the promise of a more lenient sentence. However, Nick refuses to co-operate with D’Angelo and is thrown into Sing Sing Correctional Facility. There, he meets sadistic hoodlum Tommy Udo (Richard Widmark) – his love of violence signaled in his first conversation with Nick, in which Udo promises of one of the prison guards that ‘For a nickel, I’d grab him. Stick both thumbs right in his eyes; hang on till he drops dead’.

When Nick’s wife stops writing to him, Nick suspects the worst. He discovers from another inmate, Chips Cooney (Lee Sanford), that his wife is dead, having committed suicide by sticking her head in a gas oven. As a result, Nick’s children have been place in an orphanage. Nick is visited in prison by Nettie (Coleen Gray), his daughters’ babysitter. Nettie reluctantly tells Nick that prior to her death, his wife was conducting an affair with one of Nick’s associates, a man named Rizzo. Desperate to rescue his children from a similar fate to his own, Nick agrees to help D’Angelo in return for parole and a chance at a new life. Nick meets with Earl Howser (Taylor Holmes), his defence attorney and the behind-the-scenes puppet master of the heists, and suggests subtly that Rizzo is the ‘squealer’ on another heist which D’Angelo is investigating. Howser contacts Tommy Udo, who has also been freed, and arranges for Udo to eliminate Rizzo. However, Udo is unable to find Rizzo and instead murders the hood’s wheelchair-bound mother (Mildred Dunnock) by pushing her and her wheelchair down the stairs of the apartment building in which she lives. (‘This is for knowing a squealer’, Udo snickers sadistically as he does this.) Udo meets with Nick, his former cellmate, and tells Nick of his involvement in the murder of Larry Young. Nick takes this information to D’Angelo, offering the Assistant District Attorney the identity of a witness and the location of a key piece of evidence from the crime. Nick has built a new life with Nettie; the couple have married and live under assumed names in a new town, Nick having found gainful employment as a labourer. Nettie questions whether Nick is happy in his new, far less exciting life; Nick asserts that he could never be happier. All of this is turned on its head when D’Angelo demands that Nick testify in the case against Udo. However, D’Angelo’s promises that Nick and his family will be safe ring empty when the case against Udo collapses. Realising his family is in danger from Udo’s reprisals and cognisant of Udo’s tendency to take his anger out on the relatives of ‘squealers’ (such as Rizzo’s mother), Nick begs for help from D’Angelo. Nick sends Nettie and the children away and, with a revolver, waits for Udo to come find him. D’Angelo arrives at Nick’s home first and warns Nick that if he shoots Udo, he will be prosecuted for murder. Nick realises that he must devise another method of ensnaring Udo and decides to meet the murderous gangster on his own turf.  The archetypal suffering anti-hero associated with the film noir mode, Nick is pressed from both sides of the law, and both D’Angelo and Udo place pressure on Nick through his family. D’Angelo tries to get Nick to ‘squeal’ by reminding Nick of his two children and suggesting that if he doesn’t change his ways and become an informant, they are likely to find themselves on a similar path to their father: whilst Nick is in prison for the heist that opens the picture, Nick’s wife’s suicide sends the two girls to an orphanage – which is the same start in life that Nick had. Meanwhile, when Nick’s role as an informant in the service of D’Angelo is revealed, Udo threatens Nick’s family, including Nick’s new spouse; D’Angelo’s successful attempts to use Nick’s family to railroad Nick into becoming an informant lead to Nick’s family being placed in even more immediate danger by Udo. The archetypal suffering anti-hero associated with the film noir mode, Nick is pressed from both sides of the law, and both D’Angelo and Udo place pressure on Nick through his family. D’Angelo tries to get Nick to ‘squeal’ by reminding Nick of his two children and suggesting that if he doesn’t change his ways and become an informant, they are likely to find themselves on a similar path to their father: whilst Nick is in prison for the heist that opens the picture, Nick’s wife’s suicide sends the two girls to an orphanage – which is the same start in life that Nick had. Meanwhile, when Nick’s role as an informant in the service of D’Angelo is revealed, Udo threatens Nick’s family, including Nick’s new spouse; D’Angelo’s successful attempts to use Nick’s family to railroad Nick into becoming an informant lead to Nick’s family being placed in even more immediate danger by Udo.

Initially, Nick is resistant to co-operating with D’Angelo, telling the Assistant District Attorney that he was offered a similar deal when he was caught for a previous job but nevertheless refused to ‘squeal’: ‘I took the full four years’, Nick tells D’Angelo, ‘I’m the same guy now I was then. Nothing has changed. Nothing!’ However, D’Angelo reminds Nick that something is different about Nick’s present situation: he is now a father and has ‘two kids. Two little girls. That ought to change things a little [….] You know, a man’s lucky to have kids. But having a father like you, I wouldn’t say is very lucky for them’. Nick protests that ‘I’ll take care of my family. My way’. ‘You mean by keeping your mouth shut and going to jail?’, ‘D’Angelo asks him, ‘You know why you’re doing it? Because you’ve got that good old hoodlum complex. No squealing. Desert your kids. Let ‘em starve. Let your home go to pot. But don’t squeal on some no-good hoodlums who wouldn’t turn a finger for you’. When Nick is visited by Nettie, who tells him about the suicide of his wife following her affair with Rizzo, Nick tells Nettie ‘I’m the type of guy you can’t hurt. It doesn’t matter’. However, as the narrative makes clear, Nick is all too easy to hurt – through his children and, later, his love for Nettie. This vulnerability is one which the likes of both D’Angelo and Udo are willing to exploit. Though ineffective, D’Angelo is positioned against the defence attorney Earl Howser (Taylor Holmes). Howser defends Nick and, it seems, many of the local hoodlums; but as the narrative progresses it becomes clear that Howser has a deeper involvement with these crooks. Nick reveals that Howser is the point of liaison between the thieves and their fence, and in fact it seems that Howser is responsible for commissioning many of these crimes – and has Tommy Udo on a leash, using his propensity towards violence as leverage against those who might not co-operate. When D’Angelo’s plan to capture Udo and frame Rizzo as the ‘squealer’ seems to work, Howser is the one who sends Udo on the errand to Rizzo’s house which results in Udo’s murder of Rizzo’s mother.  As played by Brian Donlevy, D’Angelo is smug and self-assured. Seated comfortably in his office, he goads Nick into testifying against Udo with the reassurance that Udo will surely be convicted of the crime for which he is being tried. However, D’Angelo’s promises are empty and his assurances are proved to be false: Udo is acquitted, placing the lives of Nick and his family in immediate danger. D’Angelo is mostly shown in his office, insulated and protected from the outside world, in comparison with Nick, who must walk the streets and deal with the likes of Udo directly. Towards the end of the film, Nick makes the comparison between D’Angelo and Udo more direct by telling D’Angelo, ‘Your side of the fence is almost as dirty as mine’. D’Angelo offers a mealy-mouthed, moralistic response (‘With one big difference’, D’Angelo says, ‘We hurt bad people, not good ones’) – but having seen how D’Angelo places Nick and his children in danger, the viewer is left with the sense that D’Angelo’s assertions are empty platitudes. When D’Angelo demands that Nick testify against Udo, that the information Nick has provided isn’t enough to convict Udo for the murder of Larry Young, Nick attempts to reason with D’Angelo, begging for the sake of his children: ‘I got kids. I got a home’, Nick says, ‘Look, I don’t care about me. Why take it out on them, just because I was a mug once?’ D’Angelo responds by offering Nick an unconvincing promise, phrased like an existential aphorism: ‘Remember this: when it’s over, you’ll be through’, D’Angelo says. The solution to Nick’s dilemma comes when he chooses not to obey D’Angelo’s commands and, at great personal risk, manipulates the law in order to ensnare Udo. As played by Brian Donlevy, D’Angelo is smug and self-assured. Seated comfortably in his office, he goads Nick into testifying against Udo with the reassurance that Udo will surely be convicted of the crime for which he is being tried. However, D’Angelo’s promises are empty and his assurances are proved to be false: Udo is acquitted, placing the lives of Nick and his family in immediate danger. D’Angelo is mostly shown in his office, insulated and protected from the outside world, in comparison with Nick, who must walk the streets and deal with the likes of Udo directly. Towards the end of the film, Nick makes the comparison between D’Angelo and Udo more direct by telling D’Angelo, ‘Your side of the fence is almost as dirty as mine’. D’Angelo offers a mealy-mouthed, moralistic response (‘With one big difference’, D’Angelo says, ‘We hurt bad people, not good ones’) – but having seen how D’Angelo places Nick and his children in danger, the viewer is left with the sense that D’Angelo’s assertions are empty platitudes. When D’Angelo demands that Nick testify against Udo, that the information Nick has provided isn’t enough to convict Udo for the murder of Larry Young, Nick attempts to reason with D’Angelo, begging for the sake of his children: ‘I got kids. I got a home’, Nick says, ‘Look, I don’t care about me. Why take it out on them, just because I was a mug once?’ D’Angelo responds by offering Nick an unconvincing promise, phrased like an existential aphorism: ‘Remember this: when it’s over, you’ll be through’, D’Angelo says. The solution to Nick’s dilemma comes when he chooses not to obey D’Angelo’s commands and, at great personal risk, manipulates the law in order to ensnare Udo.

Nick’s relationship with crime is defined by necessity and his past: a bad start in life as an orphan led Nick to a life of petty crime, facilitated by hunger and unemployment, ultimately escalating to his role as participant in the jewellery heist that opens the picture. On the other hand, Udo’s motivations are more pathological: he is an open sadist who takes glee in violence (at a boxing match, he yells at the participants, telling one of the boxers to ‘Rip his eye out! Tear it out of his head!’) and whose criminal activities seem motivated solely by a desire to be seen as the ‘big man’.  In the actor’s feature film debut, Richard Widmark’s approach to playing the giggling, sadistic Tommy Udo was reputedly based on his first response to the script, which when he read aloud to some of his friends, he found himself laughing – ‘And that’s the way I played the part in the movie’, he later reflected (Widmark, quoted in Holston, 1990: 4). Udo’s giggle ‘partially came out of nervousness. When in doubt, I’d laugh. And since this was my first picture and the mechanics of picture-making were new to me, I laughed a lot’ (Widmark, quoted in ibid.). Widmark’s role in the film was so memorable that when the picture was rereleased a few years later, after Widmark’s star had been in the ascendancy for a while in pictures which often asked him to play a Tommy Udo-like character (such as William Keighley’s The Street with No Name, 1948), the pressbooks issued for the rerelease suggested that exhibitors should ‘SELL RICHARD WIDMARK!’ (quoted in ibid.; emphasis in original). Certainly, it’s impossible to discuss the film without mentioning the infamous sequence in which Udo pushes Rizzo’s wheelchair-bound mother down a flight of stairs to her death; it’s a sequence that pushed the envelope in terms of what was acceptable within the Motion Picture Production Code, and which drew fierce criticism from some quarters. The cruelty of this sequence is made worse by Udo’s giggling and his sneering taunts (‘Im askin’ ya, where’s that squealin’ son of yours?’, he taunts Rizzo’s mother, ‘You know what I do to squealers? I let ‘em have it in the belly, so they can roll around for a long time, thinking it over’; his words find their dark echo in the film’s climax.) Critics have often suggested that the brand of giggling, motiveless and sadistic violence perpetrated by Tommy Udo within the film may be seen as a response to the trauma of the Second World War, with David Thomson going so far as to suggest that Udo’s sadism, ‘the fearful laugh, the skull showing through drawn skin’ all connect in a ‘surely conscious evocation of a concentration-camp degenerate’ (Thomson, 2010: np). In the actor’s feature film debut, Richard Widmark’s approach to playing the giggling, sadistic Tommy Udo was reputedly based on his first response to the script, which when he read aloud to some of his friends, he found himself laughing – ‘And that’s the way I played the part in the movie’, he later reflected (Widmark, quoted in Holston, 1990: 4). Udo’s giggle ‘partially came out of nervousness. When in doubt, I’d laugh. And since this was my first picture and the mechanics of picture-making were new to me, I laughed a lot’ (Widmark, quoted in ibid.). Widmark’s role in the film was so memorable that when the picture was rereleased a few years later, after Widmark’s star had been in the ascendancy for a while in pictures which often asked him to play a Tommy Udo-like character (such as William Keighley’s The Street with No Name, 1948), the pressbooks issued for the rerelease suggested that exhibitors should ‘SELL RICHARD WIDMARK!’ (quoted in ibid.; emphasis in original). Certainly, it’s impossible to discuss the film without mentioning the infamous sequence in which Udo pushes Rizzo’s wheelchair-bound mother down a flight of stairs to her death; it’s a sequence that pushed the envelope in terms of what was acceptable within the Motion Picture Production Code, and which drew fierce criticism from some quarters. The cruelty of this sequence is made worse by Udo’s giggling and his sneering taunts (‘Im askin’ ya, where’s that squealin’ son of yours?’, he taunts Rizzo’s mother, ‘You know what I do to squealers? I let ‘em have it in the belly, so they can roll around for a long time, thinking it over’; his words find their dark echo in the film’s climax.) Critics have often suggested that the brand of giggling, motiveless and sadistic violence perpetrated by Tommy Udo within the film may be seen as a response to the trauma of the Second World War, with David Thomson going so far as to suggest that Udo’s sadism, ‘the fearful laugh, the skull showing through drawn skin’ all connect in a ‘surely conscious evocation of a concentration-camp degenerate’ (Thomson, 2010: np).

However, Widmark’s nervousness may well have come from the severity of director Henry Hathaway’s regime. A notoriously strict and demanding director, Hathaway came into conflict with Victor Mature on the set of the picture. Before shooting began, Hathaway gave Mature one of his infamous ‘pep talks’, telling the actor that he should be prepared for Hathaway to treat him sternly and that any harsh words delivered by Hathaway were not meant personally. Mature responded by ‘look[ing] the director in the eye and [saying] that whenever he punched out somebody who gave him a hard time there was no need to take that personally, either’ (Pomainville, 2016: 126). On set, Mature took Widmark under his wing and told the less experienced film actor not to take Hathaway’s abuse lightly, and when Hathaway turned his attention to Widmark, Widmark reputedly reminded Hathaway of his experience as a stage and radio actor (ibid.: 127-8). The film was originally to climax with a shootout on a bus. This sequence was shot: during the filming of this scene, Hathaway fired a prop gun close to Widmark’s ear for verisimilitude. However, after the rushes had been assembled, Hathaway and producer Darryl F Zanuck agreed that the climax didn’t work in the way that it needed to, and they hired writer Philip Dunne to construct a new climax (ibid.: 128). Dunne came up with the idea of Nick Bianco tracking Udo down by investigating the nightspots Bianco knows him to haunt.  The film is similar in tone to the semidocumentary films noir that became popular in the years following the Second World War; a trend often exemplified by Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948), the semidocumentary films noir usually featured a strong emphasis on location shooting and narratives that were either ‘ripped from the headlines’ or felt very much as if they had been. In this tradition, Kiss of Death – whose trailer narrated by Walter Winchell invited direct comparisons with the contemporaneous semidocumentary films noir The House on 92nd Street (Hathaway, 1945) and Boomerang! (Elia Kazan, 1947) – was based on a number of newspaper articles written by New York prosecutor Eleazar Lipsky; consequently, its narrativisation of Nick Bianco’s struggle to ‘go straight’ has a ring of authenticity to it. Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street began a trend in the use of real locations within what would come to be defined as the semidocumentary films noir; Kiss of Death continues this, establishing the authenticity of its settings by featuring an opening sequence, the jewellery heist, which was shot in the Chrysler Building. The film is similar in tone to the semidocumentary films noir that became popular in the years following the Second World War; a trend often exemplified by Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948), the semidocumentary films noir usually featured a strong emphasis on location shooting and narratives that were either ‘ripped from the headlines’ or felt very much as if they had been. In this tradition, Kiss of Death – whose trailer narrated by Walter Winchell invited direct comparisons with the contemporaneous semidocumentary films noir The House on 92nd Street (Hathaway, 1945) and Boomerang! (Elia Kazan, 1947) – was based on a number of newspaper articles written by New York prosecutor Eleazar Lipsky; consequently, its narrativisation of Nick Bianco’s struggle to ‘go straight’ has a ring of authenticity to it. Hathaway’s The House on 92nd Street began a trend in the use of real locations within what would come to be defined as the semidocumentary films noir; Kiss of Death continues this, establishing the authenticity of its settings by featuring an opening sequence, the jewellery heist, which was shot in the Chrysler Building.

There’s a real sense of the camera negotiating the interior of the Chrysler Building within this sequence, culminating in Nick and his accomplices’ escape using one of the building’s elevators. The actors are crammed into the elevator, the car stopping on each floor to allow people to enter or alight; the camera stays on a close shot of Nick, the composition wide enough to show that he is hemmed in tightly by the other people riding in the elevator car, the lighting and exposure balanced so that each time the elevator stops and the doors open, a shaft of light illuminates his face and reveals the beads of perspiration forming on his brow. (The focus on realism, the sense of physical entrapment within an elevator car setting and the use of perspiration as an index of panic finds a strange corollary in the rather different climax of Milton Katselas’ 1975 Report to the Commissioner, a rather different crime picture which nevertheless, like Kiss of Death, reinforces its authenticity via the use of real New York locations.)  Perhaps strangely, especially given the ways in which semidocumentary films noir often avoided or downplayed the more expressionistic photography of the studiobound films noir of the period, Kiss of Death’s most visually and aurally expressionistic sequence emphasises the use of a real location, Sing Sing Correctional Facility; during Nick and Udo’s time here, the film’s photography makes strong symbolic use of the shadows cast by the bars of the cell in which they find themselves, their silhouettes cutting across the cell and dividing up the bodies and faces of the men contained within it. When Nick is in the prison’s workshop and receives news of his wife’s suicide, the dialogue is drowned out by the roar of machinery, the use of a real location underscoring the verisimilitude of the sequence; the employment of a real prison workshop and the manner in which the sound of the machinery is used recalls the later symbolic montage that opens Sam Peckinpah’s The Getaway (1972), in which the machinery within the prison workshop at Huntsville State Penitentiary is used to represent prisoner Doc McCoy’s (Steve McQueen) increasing sense of alienation and frustration. Perhaps strangely, especially given the ways in which semidocumentary films noir often avoided or downplayed the more expressionistic photography of the studiobound films noir of the period, Kiss of Death’s most visually and aurally expressionistic sequence emphasises the use of a real location, Sing Sing Correctional Facility; during Nick and Udo’s time here, the film’s photography makes strong symbolic use of the shadows cast by the bars of the cell in which they find themselves, their silhouettes cutting across the cell and dividing up the bodies and faces of the men contained within it. When Nick is in the prison’s workshop and receives news of his wife’s suicide, the dialogue is drowned out by the roar of machinery, the use of a real location underscoring the verisimilitude of the sequence; the employment of a real prison workshop and the manner in which the sound of the machinery is used recalls the later symbolic montage that opens Sam Peckinpah’s The Getaway (1972), in which the machinery within the prison workshop at Huntsville State Penitentiary is used to represent prisoner Doc McCoy’s (Steve McQueen) increasing sense of alienation and frustration.

Kiss of Death begins with narration in the third person: a disembodied female voice guides our perspective during the opening sequence of the picture. The convention of an omniscient heterodiegetic/third person narrator, informed by the paradigms of the newsreels of the day, connects the film to other semidocumentary films noir such as The Naked City, which begins with Mark Hellinger’s famous assertion that the picture was ‘not photographed in a studio’ and presents ‘the city as it is’. Later in Kiss of Death, the voice of the narrator is revealed to belong to Nettie; this revelation that the narration is actually sourced from within the diegesis changes how the audience responds to Nettie’s words. A similar technique was used in a number of other films noir of the period: for example, Crane Wilbur’s 1948 film noir Canon City, in which the third person narrator (Reed Hadley, whose voice guided a significant number of other semidocumentary films noir of the period, including Alfred L Werker’s He Walked by Night, 1948) is, as the narrative progresses, revealed to be a peripheral participant in the story. The fact that Kiss of Death is narrated by a woman is unusual, especially within semidocumentary films noir: most narrators of film noir were male, with some notable exceptions which include Anthony Mann’s Raw Deal (1948, which is narrated by Claire Trevor’s character in the film) and Michael Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce (1945, narrated by Joan Crawford). Significantly, most (all?) examples of female narration within film noir are revealed to be intradiegetic: these films are all narrated by women who have a role in the story, reinforcing by exclusion the association of documentary-like authenticity with the male voice.  Nettie’s opening narration identifies the film’s geographical and temporal setting: ‘Christmas Eve in New York’, she announces over shots of people hustling and bustling about the streets. She then goes on to establish the buried conflicts within this scene and introduce the film’s protagonist: ‘A happy time for some people, the lucky ones. Last minute shopping; presents for the kids; hurry home to light the tree and fill the stockings. For the lucky ones. Others aren’t so lucky. Nick Bianco hadn’t worked for a year. He had a record: a prison record [….] So this is how Nick went shopping for his kids’. Following this, we are presented with the heist and Bianco and his gang’s escape from it, which culminates in Bianco being shot and wounded by a uniformed policeman. Nettie’s narration reinforces the extent to which the potential consequences of this moment for Nick’s children may be the same as those faced by Nick following the death of his own father in similar circumstances: ‘The same thing happened twenty years ago to Nick’s father’, Nettie narrates over a shot of the wounded Nick lying in a gutter, ‘He died with a policeman’s bullet in him. Nick saw it. It was one of his earliest memories’. Nettie’s opening narration identifies the film’s geographical and temporal setting: ‘Christmas Eve in New York’, she announces over shots of people hustling and bustling about the streets. She then goes on to establish the buried conflicts within this scene and introduce the film’s protagonist: ‘A happy time for some people, the lucky ones. Last minute shopping; presents for the kids; hurry home to light the tree and fill the stockings. For the lucky ones. Others aren’t so lucky. Nick Bianco hadn’t worked for a year. He had a record: a prison record [….] So this is how Nick went shopping for his kids’. Following this, we are presented with the heist and Bianco and his gang’s escape from it, which culminates in Bianco being shot and wounded by a uniformed policeman. Nettie’s narration reinforces the extent to which the potential consequences of this moment for Nick’s children may be the same as those faced by Nick following the death of his own father in similar circumstances: ‘The same thing happened twenty years ago to Nick’s father’, Nettie narrates over a shot of the wounded Nick lying in a gutter, ‘He died with a policeman’s bullet in him. Nick saw it. It was one of his earliest memories’.

Video

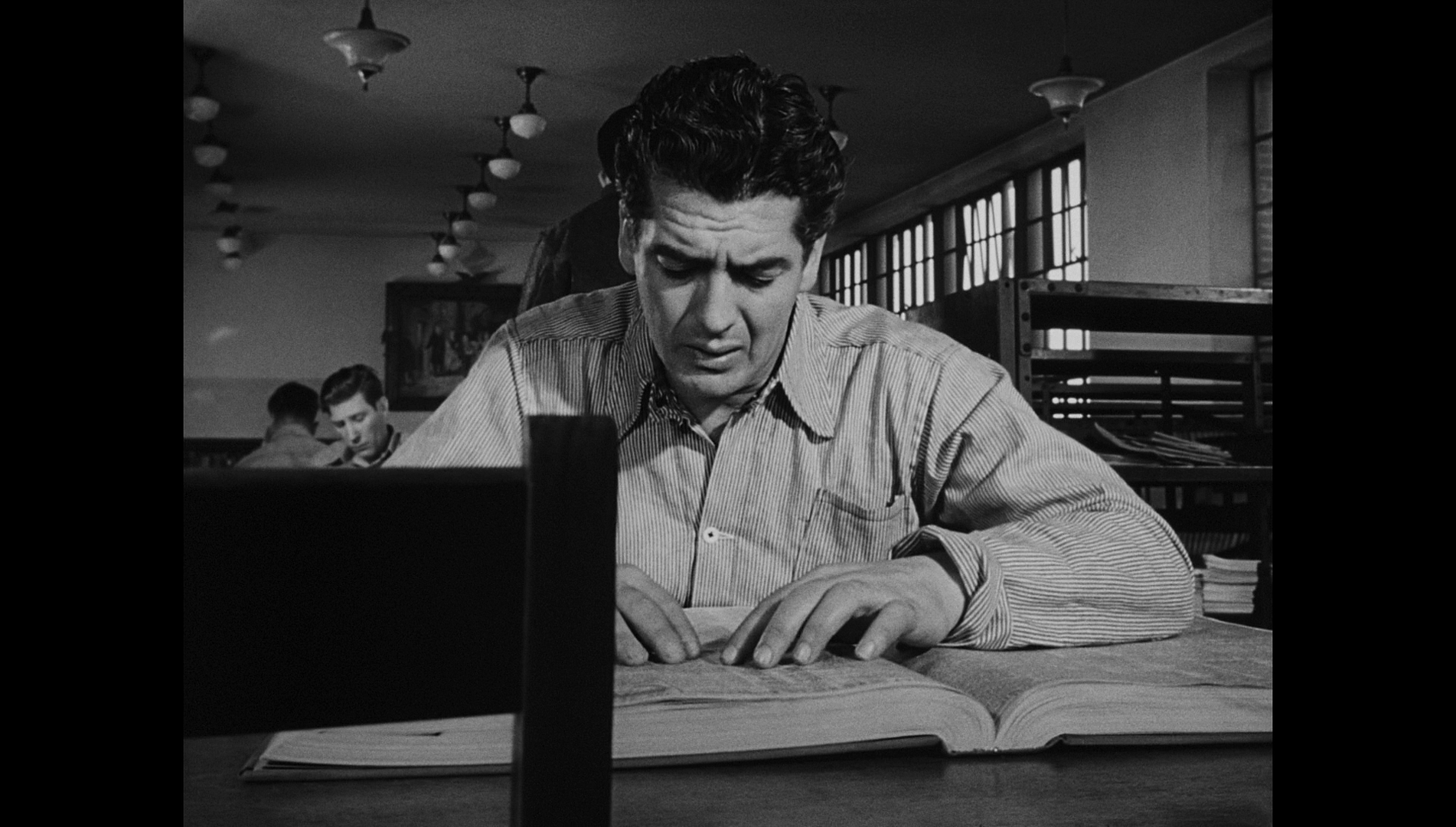

Presented uncut, the film here runs for 99:01 mins. Taking up approximately 22Gb of space on the disc, this 1080p presentation of Kiss of Death uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. Simply, the presentation is stunning. The image is rich in detail, offering a clear improvement over the already-pleasing R1 DVD release from Fox. Even more noticeable is the improvement in contrast that is a characteristic of this new HD presentation, with the film’s 35mm monochrome photography benefitting greatly from this: defined midtones are offset by deep, rich blacks (evident from the opening titles sequence, which features the film’s titles printed in ink on the pages of a ledger). Throughout the film, the image is extraordinarily clean and free from damage and debris. Finally, an excellent encode ensures the presentation preserves the structure of 35mm film, resulting in a viewing experience that is an absolute delight. Presented uncut, the film here runs for 99:01 mins. Taking up approximately 22Gb of space on the disc, this 1080p presentation of Kiss of Death uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. Simply, the presentation is stunning. The image is rich in detail, offering a clear improvement over the already-pleasing R1 DVD release from Fox. Even more noticeable is the improvement in contrast that is a characteristic of this new HD presentation, with the film’s 35mm monochrome photography benefitting greatly from this: defined midtones are offset by deep, rich blacks (evident from the opening titles sequence, which features the film’s titles printed in ink on the pages of a ledger). Throughout the film, the image is extraordinarily clean and free from damage and debris. Finally, an excellent encode ensures the presentation preserves the structure of 35mm film, resulting in a viewing experience that is an absolute delight.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track (in English). This is rich and deep, with excellent range, and is clear throughout. It is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing, which are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes:  - An audio commentary with film noir historians James Ursini and Alain Silver. This is the same audio commentary that was featured on the R1 DVD release from Fox. Ursini and Silver know their stuff, and this commentary track is absolutely superb. The pair reflect on the picture’s production history and reception, discussing its relationship with other films noir of the era, especially the semidocumentary films noir, the use of real locations during the shoot and some of the heavy Christian symbolism within the picture. - An audio commentary with film noir historians James Ursini and Alain Silver. This is the same audio commentary that was featured on the R1 DVD release from Fox. Ursini and Silver know their stuff, and this commentary track is absolutely superb. The pair reflect on the picture’s production history and reception, discussing its relationship with other films noir of the era, especially the semidocumentary films noir, the use of real locations during the shoot and some of the heavy Christian symbolism within the picture.

- An interview with Richard Widmark (18:30). Here, in an edited interview recorded at the National Film Theatre in 2002, the actor reflects on his early career before talking about Kiss of Death. Widmark offers some anecdotes about the film and its production which will be familiar to many devotees of film noir (eg, Hathaway’s insistence that Udo be played by a non-actor, and his choice of a street ‘face’ named Harry the Hipster) but which are fascinating to hear first-hand from Widmark himself. Widmark also talks about many of his other experiences in filmmaking, including his working relationship with John Ford. Widmark also reflects on his approach to acting. - The film’s trailer (2:21).

Overall

Kiss of Death was controversial at the time of its original release, with Udo’s cruel treatment of Rizzo’s mother becoming symbolic for many of Hollywood’s attempts to flout the strictures imposed on it by the Motion Picture Production Code. The film has also had some vocal detractors amongst fans of film noir, with Mature’s performance sometimes being singled out for criticism. Certainly, Mature’s presence in the film seems swamped by Widmark’s incredible portrayal of Tommy Udo, a role that would come to haunt Widmark throughout his long career; the contrast between the energy and vitality of Udo, the chief villain, and the exhausted fatalism of Nick Bianco, the anti-hero, finds its way into many subsequent films noir and neo-noir pictures, up to and including films such as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982, with its conflict between Rick Deckard and Roy Batty) and Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008, in its conflict between the Batman and the Joker). Kiss of Death was controversial at the time of its original release, with Udo’s cruel treatment of Rizzo’s mother becoming symbolic for many of Hollywood’s attempts to flout the strictures imposed on it by the Motion Picture Production Code. The film has also had some vocal detractors amongst fans of film noir, with Mature’s performance sometimes being singled out for criticism. Certainly, Mature’s presence in the film seems swamped by Widmark’s incredible portrayal of Tommy Udo, a role that would come to haunt Widmark throughout his long career; the contrast between the energy and vitality of Udo, the chief villain, and the exhausted fatalism of Nick Bianco, the anti-hero, finds its way into many subsequent films noir and neo-noir pictures, up to and including films such as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982, with its conflict between Rick Deckard and Roy Batty) and Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight (2008, in its conflict between the Batman and the Joker).

In the role of Nick Bianco, Mature’s sense of dogged persecution haunts the film: he’s a fulltime loser, his status as such and his weary-eyed, hangdog expression finding strange echoes in Robert Mitchum’s role as the doomed ‘squealer’ in Peter Yates’ 1973 adaptation of the thematically similar 1972 novel by George V Higgins, The Friends of Eddie Coyle. (Barbet Schroeder’s 1995 neo-noir remake of Kiss of Death attempts to engage with the Mature-Widmark pairing by offering David Caruso in the Vic Mature role and Nic Cage functioning as a substitute for Widmark.) I may be biased, as Richard Widmark was my grandmother’s favourite actor, and so I grew up watching his films (this and Elia Kazan’s Panic in the Streets, 1950, were particular favourites of hers), but for my money Kiss of Death is a superb example of 1940s film noir, marrying the paradigms of the semidocumentary films noir of the period (eg, location shooting, the voiceover narration) with the melodrama of the more studiobound noir pictures of the 1940s to result in a film that has a defined sense of fatalism and verisimilitude in equal doses. Signal One Entertainment’s Blu-ray release of the film contains an exceptional presentation of the main feature whilst carrying over the superb audio commentary from the R1 DVD release (by Ursini and Silver) and adding to this a fascinating archival interview with Widmark. A very pleasing release, this continues Signal One’s run of excellent discs; fans of film noir will find this to be an essential purchase. References: Holston, Kim R, 1990: Richard Widmark: A Bio-Bibliography. London: Greenwood Pomainville, Harold N, 2016: Henry Hathaway: The Lives of a Hollywood Director. London: Rowman and Littlefield Thomson, David, 2010: The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. London: Hachette (Fifth Edition)

|

|||||

|