|

|

Trip (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (4th January 2016). |

|

The Film

The Trip (Roger Corman, 1967) The Trip (Roger Corman, 1967)

Like many of Roger Corman’s other films, The Trip (1967) was shot quickly and cheaply and, tapping into the zeitgeist, offered a considerable return on Corman’s initial financial investment. The film was scripted by Jack Nicholson and starred Peter Fonda, with Dennis Hopper in a supporting role. Hopper even directed a number of sequences, when Corman expressed an unwillingness to shoot in the desert. Working together, this trio (Hopper, Fonda and Nicholson) would go on to make the counterculture classic of the Hollywood Renaissance, Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1969). Corman once asserted that ‘You can almost chart a line from The Wild Angels [Corman’s 1966 biker picture] to The Trip to Easy Rider, following the counterculture of the day’ (Corman, quoted in Love, 2009: 161). Adding to the countercultural credentials of The Trip is an appearance by Bruce Dern, as a Timothy Leary-style guru who aids Peter Fonda’s character on his first acid trip. The film opens with Paul Graves (Peter Fonda) directing a television commercial on a beach. He is interrupted in his work by his wife Sally (Susan Strasberg), who reminds Paul that he has missed an appointment to arrange the couple’s divorce. After the shoot, Paul meets with John (Bruce Dern) in a nightclub. They drive out to a house, with the phrase ‘Psychedelic Temple’ written on the door, to meet with Max (Dennis Hopper). There, Paul meets Glenn (Salli Sachsi). Max is a dealer, and John and Paul score from Max some LSD. They return to John’s place, where John promises to stay with Paul whilst he experiences his first acid trip. Paul experiences hallucinations of a medieval forest, a desert, and a strange carnival. Exiting the trip briefly, he asks John for a drink; John leaves the room to fetch Paul some apple juice. Paul experiences terror and hides in a closet, exiting to find what appears to be the corpse of John. Paul flees from the building in fear for his life (unaware that John is still alive and well, and that what Paul saw was an hallucination), running along the Sunset Strip where he encounters Glenn. Glenn takes Paul home; the couple sleep together. In the morning, Glenn asks Paul about his trip.  The opening sequence subtly destabilises the audience’s perception from the get-go, paving the way for the more radical filmmaking techniques used later in the picture to depict Paul’s experience of taking LSD. As the film opens, we are presented with a couple kissing – not an unusual sight, until we realise that whilst they are kissing, they are standing on a body of water (presumably, the Pacific Ocean). The camera pans away to reveal Paul standing on the edge of a low cliff. He’s with a cameraman; we realise that the scene we have just witnessed is from a film-within-a-film. The dialogue anchors this more firmly by telling us that Paul is a director of television commercials. During his work, Paul is approached by Sally, chastising Paul for missing an appointment to arrange their divorce. ‘Well, Sally’, Paul says softly, ‘I work very hard. I can’t just leave in the middle of the day and come into town to sign divorce papers’. Though it’s not stated explicitly, by Fonda’s acting (Paul’s lack of surprise) the viewer seems to be led to the conclusion that Paul has missed the appointment deliberately, and that he is avoiding the fact of the breakdown of his marriage and impending divorce. Later in the film, during his hallucinations, Paul sees himself both with Sally, suggesting a continued attachment to her from which he struggles to break free, and with Glenn, indicating a desire for a new relationship with a different woman. The opening sequence subtly destabilises the audience’s perception from the get-go, paving the way for the more radical filmmaking techniques used later in the picture to depict Paul’s experience of taking LSD. As the film opens, we are presented with a couple kissing – not an unusual sight, until we realise that whilst they are kissing, they are standing on a body of water (presumably, the Pacific Ocean). The camera pans away to reveal Paul standing on the edge of a low cliff. He’s with a cameraman; we realise that the scene we have just witnessed is from a film-within-a-film. The dialogue anchors this more firmly by telling us that Paul is a director of television commercials. During his work, Paul is approached by Sally, chastising Paul for missing an appointment to arrange their divorce. ‘Well, Sally’, Paul says softly, ‘I work very hard. I can’t just leave in the middle of the day and come into town to sign divorce papers’. Though it’s not stated explicitly, by Fonda’s acting (Paul’s lack of surprise) the viewer seems to be led to the conclusion that Paul has missed the appointment deliberately, and that he is avoiding the fact of the breakdown of his marriage and impending divorce. Later in the film, during his hallucinations, Paul sees himself both with Sally, suggesting a continued attachment to her from which he struggles to break free, and with Glenn, indicating a desire for a new relationship with a different woman.

The LSD presents Paul with an escape from the trauma of his life and his impending divorce. (This is an element of the script that, it has been said, was autobiographical for Nicholson, who at the time of writing the film was undergoing his divorce from Sandra Knight, an experience that he found deeply unpleasant.) At Max’s Psychedelic Temple, when he and John attempt to buy some acid from Max, Glenn asks Paul why he wants to take acid. ‘Insight’, he answers her, ‘I really think that I’ll find something out about myself’. The trip itself is punctuated by moments of ‘insight’ stereotypical of late-1960s counterculture: ‘I feel like everything’s alive’, Paul says at one point, followed by the repeated assertion ‘Never saw that before’. (In one deeply funny exchange, John tries to assuage Paul’s increasingly paranoid anxieties by asking if he would like to return to the living room. ‘The living room?’, Paul repeats before adding a new emphasis and smiling as if in a moment of profound epiphany: ‘The living room!’)  The potential for a ‘bad trip’ is established from the outset. At Max’s Psychedelic Temple, John and Paul listen as Max tells them of a bad trip he experienced recently. Returning to his home, John asserts the importance of feeling comfortable and relaxed in order to avoid experiencing a bad trip, and he promises to remain with Paul at all times. John also has at hand a dose of Thorazine ‘in case you happen to go on a bad trip. This brings you back immediately’, he tells his friend. John tells Paul that ‘You have to have absolute confidence and faith in me’, asserting that ‘You got to do exactly like they say. You got to turn off your mind and relax and then just float downstream’. However, Paul is visibly anxious, pacing the apartment nervously. As he puts on the eye mask that John gives him, the photography presents us with Paul’s subjective experience, showing the act of placing the mask over his eyes via a point-of-view shot, followed by a black screen over which we can hear Paul’s heartbeat. This then segues into a kaleidoscope of colours and patterns; during its start, at least, we experience Paul’s trip subjectively, the abstract images gradually intercut almost subliminally with more representational photography, beginning with shots of the beach where Paul was seen directing the commercial in the film’s opening sequence. The potential for a ‘bad trip’ is established from the outset. At Max’s Psychedelic Temple, John and Paul listen as Max tells them of a bad trip he experienced recently. Returning to his home, John asserts the importance of feeling comfortable and relaxed in order to avoid experiencing a bad trip, and he promises to remain with Paul at all times. John also has at hand a dose of Thorazine ‘in case you happen to go on a bad trip. This brings you back immediately’, he tells his friend. John tells Paul that ‘You have to have absolute confidence and faith in me’, asserting that ‘You got to do exactly like they say. You got to turn off your mind and relax and then just float downstream’. However, Paul is visibly anxious, pacing the apartment nervously. As he puts on the eye mask that John gives him, the photography presents us with Paul’s subjective experience, showing the act of placing the mask over his eyes via a point-of-view shot, followed by a black screen over which we can hear Paul’s heartbeat. This then segues into a kaleidoscope of colours and patterns; during its start, at least, we experience Paul’s trip subjectively, the abstract images gradually intercut almost subliminally with more representational photography, beginning with shots of the beach where Paul was seen directing the commercial in the film’s opening sequence.

The beach is the site of Paul’s trauma: the place where he was reminded of his impending divorce from Sally. From the beach, Paul is taken in his trip to the bedroom where he has sex with both Sally and Glenn, a kaleidoscope of colours spilling over their bodies. Upon his first ‘exit’ from the trip, Paul babbles to John, telling him ‘It’s true that I love her, but I don’t know what that means, so I’m sure I’ll suffer. I don’t want to suffer, man’. Paul’s anxieties gradually surface during his trip, when a vision of a forest and a naked women accompanied by two men on horseback, in medieval dress, suddenly ‘turns’ and Paul finds himself pursued by the horses and their riders, fleeing to a cave where he hears a witch-like cackling. Paul soon finds himself in a Gothic castle, perhaps indexical of his perception of his own suffering in the breakup of his marriage to Sally, in a moment which alludes to Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe pictures; intercut with shots of Paul running through the desert, he advances through the castle and sees a vision of himself hanged before witnessing his own funeral, his body laid out on the beach and cremated by four horsemen. From here, Paul ‘exits’ the trip and begs John, ‘Oh, no. I’m gonna die, man. I don’t wanna die [….] I’m frightened to die, man’. John reassures him, ‘You’re not gonna die. That’s just a thought in your mind. It’s all in your mind. There’s no fear in it. It’s in your interpretation of it, that’s where the fear is’. In response to John’s phenomenological advice, Paul declares ‘I can see right into my brain. Oh, you were right: everything’s in the head’.  Paul experience of the trip becomes increasingly paranoid. He witnesses a strange carnival which is presided over by Max, who asks Paul pointed questions about his life and his marriage: ‘It’s a living’, Paul responds to Max’s questioning of Paul’s career, ‘Well, everybody’s got to make a living. What choice do I have? What else can I do that’s any better?’ Max responds by telling Paul, ‘It’s a simple failure. No real love, and total self-involvement’. (Paul’s encounter with Max, which encourages Paul to reflect on how he approaches his life, might cause the viewer to recall Ebenezer Scrooge’s encounters with the ghosts in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.) The paranoia culminates in Paul’s vision of John dead, a bullet hole in his head. Following this, Paul flees through the streets, finding himself in a house watching a television news broadcast about the Vietnam War. He is interrupted by a little girl and her family, and flees again. Finally, after visiting a nightclub before heading towards Max’s place, Paul is reunited with Glenn. ‘I feel like I’m losing something’, Paul tells her. ‘That’s a common feeling’, she says. ‘Let it go’. Paul and Glenn spend the night together. ‘Did you find what you were looking for? The insight?’, Glenn asks, her question referring to her earlier conversation with Paul during their first meeting, and being phrased ambiguously: is she alluding to Paul’s ‘trip’ or his first sexual encounter with a woman other than his wife? ‘Yeah, I think…’, Paul begins, pausing before adding, ‘Like, I love you’. ‘And everybody else?’, Glenn asks. ‘Yeah, and everybody else’, he says. ‘It’s easy now’, she tells him, referring to the euphoric state in which he’s in, ‘Wait till tomorrow’. ‘Yeah, well, I’ll think about that tomorrow’, Paul says, lost in the thought and finally able to live for the moment. Paul experience of the trip becomes increasingly paranoid. He witnesses a strange carnival which is presided over by Max, who asks Paul pointed questions about his life and his marriage: ‘It’s a living’, Paul responds to Max’s questioning of Paul’s career, ‘Well, everybody’s got to make a living. What choice do I have? What else can I do that’s any better?’ Max responds by telling Paul, ‘It’s a simple failure. No real love, and total self-involvement’. (Paul’s encounter with Max, which encourages Paul to reflect on how he approaches his life, might cause the viewer to recall Ebenezer Scrooge’s encounters with the ghosts in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.) The paranoia culminates in Paul’s vision of John dead, a bullet hole in his head. Following this, Paul flees through the streets, finding himself in a house watching a television news broadcast about the Vietnam War. He is interrupted by a little girl and her family, and flees again. Finally, after visiting a nightclub before heading towards Max’s place, Paul is reunited with Glenn. ‘I feel like I’m losing something’, Paul tells her. ‘That’s a common feeling’, she says. ‘Let it go’. Paul and Glenn spend the night together. ‘Did you find what you were looking for? The insight?’, Glenn asks, her question referring to her earlier conversation with Paul during their first meeting, and being phrased ambiguously: is she alluding to Paul’s ‘trip’ or his first sexual encounter with a woman other than his wife? ‘Yeah, I think…’, Paul begins, pausing before adding, ‘Like, I love you’. ‘And everybody else?’, Glenn asks. ‘Yeah, and everybody else’, he says. ‘It’s easy now’, she tells him, referring to the euphoric state in which he’s in, ‘Wait till tomorrow’. ‘Yeah, well, I’ll think about that tomorrow’, Paul says, lost in the thought and finally able to live for the moment.

Nicholson reputedly wished to play the role of John, having included some autobiographical elements within the script, and whilst taking acid regularly towards the end of his marriage to Sandra Knight. He was upset when Corman cast Dern in the part (Eliot, 2013: np). ‘Most of the trauma I was going through at the time is written into that film’, Nicholson later confessed in reference to the writing of The Trip during his divorce from Knight (Nicholson, quoted in Parker, 2007: np). Reflecting on his friendship with Nicholson, Dern later commented that ‘I’ll never forget that day, when I saw a wreck of a guy writing that script because of the circumstances of his own life, the emotional grips that were on him, the frailty of the human being’ (Dern, 2007: 64). Commenting on the character of John, Nicholson later told Dern that ‘I wrote myself a part in the fucking Trip and Roger wouldn’t let me play it. I never told you it was for me. I’d have been a lot better than you because I wrote it myself and I understood it’ (Nicholson, quoted in ibid.: 89). Nicholson used his own experiences with LSD in the writing of the script, and Fonda had also tried LSD a few years prior to the making of the film, with a ‘friend administer[ing] the drug and supervis[ing] the trip “because he knew my head was really fucked up”’ (Parker, op cit.: np; quoting Fonda). Fonda ‘was able to pass onto Nicholson authoritative recollections of seeing huge worms crawl out of biscuits, eating a plum that was alive, seeing his wife sitting beside him and all that kind of hallucinatory experience’ (ibid.). Hopper, playing the dealer Max, tried acid in order to better understand his role in the film: ‘I thought, “Well, if I’m dealing it, I better understand what it is”’ (Hopper, quoted in Winkler, 2012: np). Hopper compared the experience with taking peyote, asking himself that because he had already experienced peyote, ‘I said what do I want to do this chemical for? One is like eating a flower, and one is like eating an IBM machine. I had a really great trip. Amazing’ (Hopper, quoted in ibid.). To prepare himself for shooting the picture, Corman also took LSD himself. Bruce Dern asked Corman ‘How did you research this movie?’, and Corman told Dern ‘I took a tab of acid and I lay down with my nose an eight of an inch off the ground for six hours’ (Dern, op cit.: 65; quoting Corman). Dern had no such intentions, telling Corman ‘I don’t know what acid looks like. I still don’t know what cocaine looks like. It’s mumbo jumbo to me’ (ibid.). For his part, Corman made the film with the intention of ‘dramatiz[ing] the experience of taking lysergic acid diethylamide in a way as personal, subjective, optically enhanced, and “realistic” as was possible onscreen’ (Grant, 2008: 187).  Corman stated that ‘More than plot, I wanted an impressionistic, free-form trip in every sense’, with ‘The audience [knowing] the terror, the exhilaration, the loneliness and the ecstasy of a trip by the time Fonda finishes with them’ (Corman, quoted in Siff, 2015: 186). With its use of symbolic montage (one sequence cuts between Paul ingesting acid and a slow-motion shot of a lizard shooting out its long tongue to catch its prey), its hallucinatory lighting and its arrhythmic editing, The Trip looks more like a European avant-garde film than a Hollywood picture. Upon reading Nicholson’s script, Fonda suggested that it could have been written by Fellini (Parker, op cit.: np). This aspect of the film – its connection with European art cinema – was highlighted in some of the contemporary reviews of it. For example, Bosley Crowther suggested that if Corman’s picture ‘is a fair indication of what one sees when high on psychedelic drugs […] the experience is not very different from looking at some of the phantasmagoric effects in movies like [Fellini’s] Juliet of the Spirits’ (Crowther, quoted in Eliot, 2013: np). In fact, there are direct visual allusions within the film to the work of filmmakers like Jean Cocteau (for example, the sequence in which Paul, high on acid, gazes into the mirror, which recalls the use of mirrors in a number of Cocteau’s films) and Ingmar Bergman (the medieval horsemen who pursue Paul in his hallucinations seem straight out of Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, 1957). Corman stated that ‘More than plot, I wanted an impressionistic, free-form trip in every sense’, with ‘The audience [knowing] the terror, the exhilaration, the loneliness and the ecstasy of a trip by the time Fonda finishes with them’ (Corman, quoted in Siff, 2015: 186). With its use of symbolic montage (one sequence cuts between Paul ingesting acid and a slow-motion shot of a lizard shooting out its long tongue to catch its prey), its hallucinatory lighting and its arrhythmic editing, The Trip looks more like a European avant-garde film than a Hollywood picture. Upon reading Nicholson’s script, Fonda suggested that it could have been written by Fellini (Parker, op cit.: np). This aspect of the film – its connection with European art cinema – was highlighted in some of the contemporary reviews of it. For example, Bosley Crowther suggested that if Corman’s picture ‘is a fair indication of what one sees when high on psychedelic drugs […] the experience is not very different from looking at some of the phantasmagoric effects in movies like [Fellini’s] Juliet of the Spirits’ (Crowther, quoted in Eliot, 2013: np). In fact, there are direct visual allusions within the film to the work of filmmakers like Jean Cocteau (for example, the sequence in which Paul, high on acid, gazes into the mirror, which recalls the use of mirrors in a number of Cocteau’s films) and Ingmar Bergman (the medieval horsemen who pursue Paul in his hallucinations seem straight out of Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, 1957).

The dialogue within the picture is intended to be ‘evocative, not suggestive. There is no “point,” no “meaning” to this film, but one gets a fairly accurate sense of the kinds of thought patterns and linkages made by trippers, at least at the time’ (Grant, op cit.: 187). To this end, the visual design of the film takes inspiration from the work of Peter Max, the contemporaneous graphic artist who used primary colours in a way intended to be ‘stimulating for those on drugs but innocuous for straights who would choose his posters to decorate offices and waiting rooms’ (ibid.). Ultimately, though its depiction of the effects of ‘dropping acid’ are hyperbolic, The Trip ‘does give a chilling sense of the way realistic everyday perception merged with fantasy’: as Barry Keith Grant says, there are a number of scenes in the picture in which Paul struggles to be able to determine whether he is still ‘in’ the trip or has exited it, and ‘the strongest of these [are] effected in conversations with John where John cannot quite make out how to resolve the ambiguities in what Paul is saying in his “realizations”’ (ibid.: 187, 188). Where previous films had equated the use of illegal drugs with criminality and the criminal class, in The Trip Paul is a respectable middle-class professional, a director of television commercials who looks towards LSD to expand his mind at a time of crisis (during his divorce from his wife). Corman intended for the trip sequences to offer a form of what he called ‘total cinema’, in which the film’s viewers would be ‘taken through the emotions and experiences of an LSD trip’ (Siff, 2015: 186). Corman later said in interview that ‘everyone who was involved in the production on every level’ had experienced acid, and ‘we believed in the potential of LSD and, when I made the film, I approved of drug use’ (Corman, quoted in Schupp, 1973: 86). However, Corman also ‘wanted to show the dramatic effects of a “bad” trip, even though my own experience may have been positive and pleasant. I owed it to myself to show both sides […] for the sake of fairness’ (Corman, quoted in ibid.). Because of Corman’s refusal to represent Paul, John and Max as criminals or deviants, The Trip was criticised by some for glamourising the use of narcotics, with Judith Crist labeling the film as ‘an hour and a half commercial for LSD’ (Crist, quoted in ibid.). The supposed glamourisation of LSD use was the reason for the film’s ban in the UK, despite the addition to overseas prints of a spoken prologue (included as an ‘extra’ on this Blu-ray release) warning viewers of the dangers associated with LSD, and also added a ‘cracked screen’ effect at the end of the film to remove the ambiguity of the film’s final moments and suggest that Paul had been irreparably ‘damaged’ by his LSD experience. (This was one of the elements of the film which the studio imposed in order ‘to give the impression of an antidrug film’, something which upset Corman and preceded AIP’s more severe re-editing of Gas-s-s-s in 1970.)  In his 1973 memoir What the Censor Saw, John Trevelyan stated that when submitted to the BBFC for classification, The Trip was shown to three psychiatrists, ‘all of whom condemned it as meretricious, inaccurate in its representation and therefore dangerous’ (Trevelyan, quoted in BBFC, 2015: np). Trevelyan suggested that in protest of the ban on the film, the London-based representative of the company who submitted the picture to the BBFC ‘brought his own psychiatrist’ to the BBFC’s offices ‘only to find that his psychiatrist agreed that it was a dangerous film’ (ibid.). Their condemnation of the film was the principle reason for its ban in 1967. The film was shown at festivals in London and Edinburgh, and at the ICA in 1971, and in the same year it was resubmitted to the BBFC in a cut version, during Stephen Murphy’s tenure as the BBFC’s Secretary; it was at this point that the BBFC rejected the film for the second time, with one of the examiners commenting that ‘Although the film has “aged” and a lot of it seems rather silly (as it did at the time of first viewing), the deterrent episodes (eg. the nightmare quality of a bad trip) are not strong enough to counterbalance the pleasurable aspects of L.S.D. as depicted in the film. In our opinion it might well tempt certain young people to experiment with the drug. By a coincidence only last week two young men were found wandering about a Folkestone beach, naked and out of their minds, having taken L.S.D. Something much more serious could have happened to them. So we decided not to lift the ban on this film’ (Anonymous BBFC Examiner, quoted in ibid.). In his 1973 memoir What the Censor Saw, John Trevelyan stated that when submitted to the BBFC for classification, The Trip was shown to three psychiatrists, ‘all of whom condemned it as meretricious, inaccurate in its representation and therefore dangerous’ (Trevelyan, quoted in BBFC, 2015: np). Trevelyan suggested that in protest of the ban on the film, the London-based representative of the company who submitted the picture to the BBFC ‘brought his own psychiatrist’ to the BBFC’s offices ‘only to find that his psychiatrist agreed that it was a dangerous film’ (ibid.). Their condemnation of the film was the principle reason for its ban in 1967. The film was shown at festivals in London and Edinburgh, and at the ICA in 1971, and in the same year it was resubmitted to the BBFC in a cut version, during Stephen Murphy’s tenure as the BBFC’s Secretary; it was at this point that the BBFC rejected the film for the second time, with one of the examiners commenting that ‘Although the film has “aged” and a lot of it seems rather silly (as it did at the time of first viewing), the deterrent episodes (eg. the nightmare quality of a bad trip) are not strong enough to counterbalance the pleasurable aspects of L.S.D. as depicted in the film. In our opinion it might well tempt certain young people to experiment with the drug. By a coincidence only last week two young men were found wandering about a Folkestone beach, naked and out of their minds, having taken L.S.D. Something much more serious could have happened to them. So we decided not to lift the ban on this film’ (Anonymous BBFC Examiner, quoted in ibid.).

The film was submitted again in 1980, after James Ferman had taken over as Secretary, and was once again rejected. An examiner commented that ‘The film is a much better one than I had anticipated, and interestingly educational: at the end I felt I had a pretty good idea of what an acid trip was like. I could also see the excitement and appeal of it. Although the film is not the commercial for acid I thought it was going to be at the outset […] I think we'd need some pretty solid information and evidence of changed circumstances or attitudes in the last decade before passing this. One day it may be passable as a document of social history, but not, I would have thought, yet’ (Anonymous BBFC Examiner, quoted in ibid.). Citing ‘an increase in the availability of LSD, James Ferman suggested that though ‘we found it more interesting and less exploitative than expected, we all take the view that it may have the effect of normalising and legitimising a drug experience which remains dangerous as well as criminal’ (Ferman, quoted in ibid.). Submitted once more to the BBFC by the Rank Video Library for video classification in 1983; this time, the opinions of the examiners who viewed the film were split. One examiner commented that ‘the experience it presents is basically dated and banal, and it does present the bad trip with the good trip, and the foolishness of it all is seen from the outside. Quite honestly, I think that this video would bore the pants off most teenagers I know. They'd rather see a video nasty’; on the other hand, a different examiner suggested that ‘I can see no way in which The Trip can be seen as a warning, despite the message tacked on the beginning - it clearly shows LSD as, at worst, an interesting thing to experiment with from which the hero emerges with deeper (?) insights’ (Anonymous BBFC Examiners, quoted in ibid.). The Trip was formally rejected for video classification five years later, in 1988, and once again in 1992, only being passed by the BBFC in 2002, when it was submitted by FilmFour with the intention of broadcasting it on their television channel.  Corman originally refused to shoot in the desert, but Fonda ‘thought we needed the script’s desert sequences’, and he told ‘Corman that I’d gotten some cameras and a friend who could operate them and that we needed the footage’ (Fonda, quoted in Winkler, op cit.: np). Rather than simply asking Corman for some money, Fonda approached shooting these sequences in a roundabout way: he rented a camera, found a cameraman and asked Hopper to direct the footage. Fonda reflected that ‘Dennis got some beautiful, beautiful stuff of me in the dunes, with water behind me, water going into my profile and bursting behind me, water lit by the sun. We pulled off some of the best shots of the film’ (Fonda, quoted in ibid.). Hopper’s work directing the second unit sequences for The Trip convinced Fonda that Hopper was capable of directing the project which became Easy Rider (ibid.). Corman, originally scheduled to produce Easy Rider before the project moved from AIP to Columbia, was equally impressed with the material that Hopper shot for The Trip and this ‘was one of the reasons I was confident and went along with the combination of Peter to produce and Dennis to direct’ (Corman, quoted in Love, op cit.: 161). It has been suggested too that Hopper’s handling of some of the more hallucinatory sequences in the script for The Trip employed a ‘visual vocabulary and style’ that would be ‘reproduced and refined in the LSD-induced’ hallucination sequence in Easy Rider. Corman originally refused to shoot in the desert, but Fonda ‘thought we needed the script’s desert sequences’, and he told ‘Corman that I’d gotten some cameras and a friend who could operate them and that we needed the footage’ (Fonda, quoted in Winkler, op cit.: np). Rather than simply asking Corman for some money, Fonda approached shooting these sequences in a roundabout way: he rented a camera, found a cameraman and asked Hopper to direct the footage. Fonda reflected that ‘Dennis got some beautiful, beautiful stuff of me in the dunes, with water behind me, water going into my profile and bursting behind me, water lit by the sun. We pulled off some of the best shots of the film’ (Fonda, quoted in ibid.). Hopper’s work directing the second unit sequences for The Trip convinced Fonda that Hopper was capable of directing the project which became Easy Rider (ibid.). Corman, originally scheduled to produce Easy Rider before the project moved from AIP to Columbia, was equally impressed with the material that Hopper shot for The Trip and this ‘was one of the reasons I was confident and went along with the combination of Peter to produce and Dennis to direct’ (Corman, quoted in Love, op cit.: 161). It has been suggested too that Hopper’s handling of some of the more hallucinatory sequences in the script for The Trip employed a ‘visual vocabulary and style’ that would be ‘reproduced and refined in the LSD-induced’ hallucination sequence in Easy Rider.

Corman’s run-and-gun shooting technique is mirrored in the rapid pace of the finished film. Dern once reflected that ‘Roger was like that in everything. I mean—there were no permits. There were no rules’ (Dern, quoted in Love, op cit.: 167; emphasis in original). Dern comments on a specific scene from the film, in which Paul, high on his acid trip, runs into a nightclub, the Whisky a Go Go. The club’s owners weren’t informed of the crew’s presence: ‘we didn’t tell anybody we were gonna do that. We didn’t tell anybody we were gonna be filming there’ (Dern, quoted in ibid.; emphasis in original). Corman told Fonda and Dern, ‘remember, there’s no Take Two here. ‘Cause as soon as they see the camera on the street, they’re gonna come and get us, and the Whisky is gonna want to know what you guys are doing, and somebody will want to be paid’ (Corman, quoted by Dern in ibid.). What Dern, Fonda, Hopper and Nicholson learnt from Corman, Dern says, was ‘courage […] Enormous courage’ (ibid.). In comparison with the film’s previous DVD releases, which contained the AIP-imposed prologue and ending, Signal One’s new Blu-ray presentation of The Trip is of the original cut, sans the opening narration added by AIP and minus the cracked screen effect at the end of the picture – both of which are included in the extra features on this disc. The film, as presented here, runs for 81:34 mins.

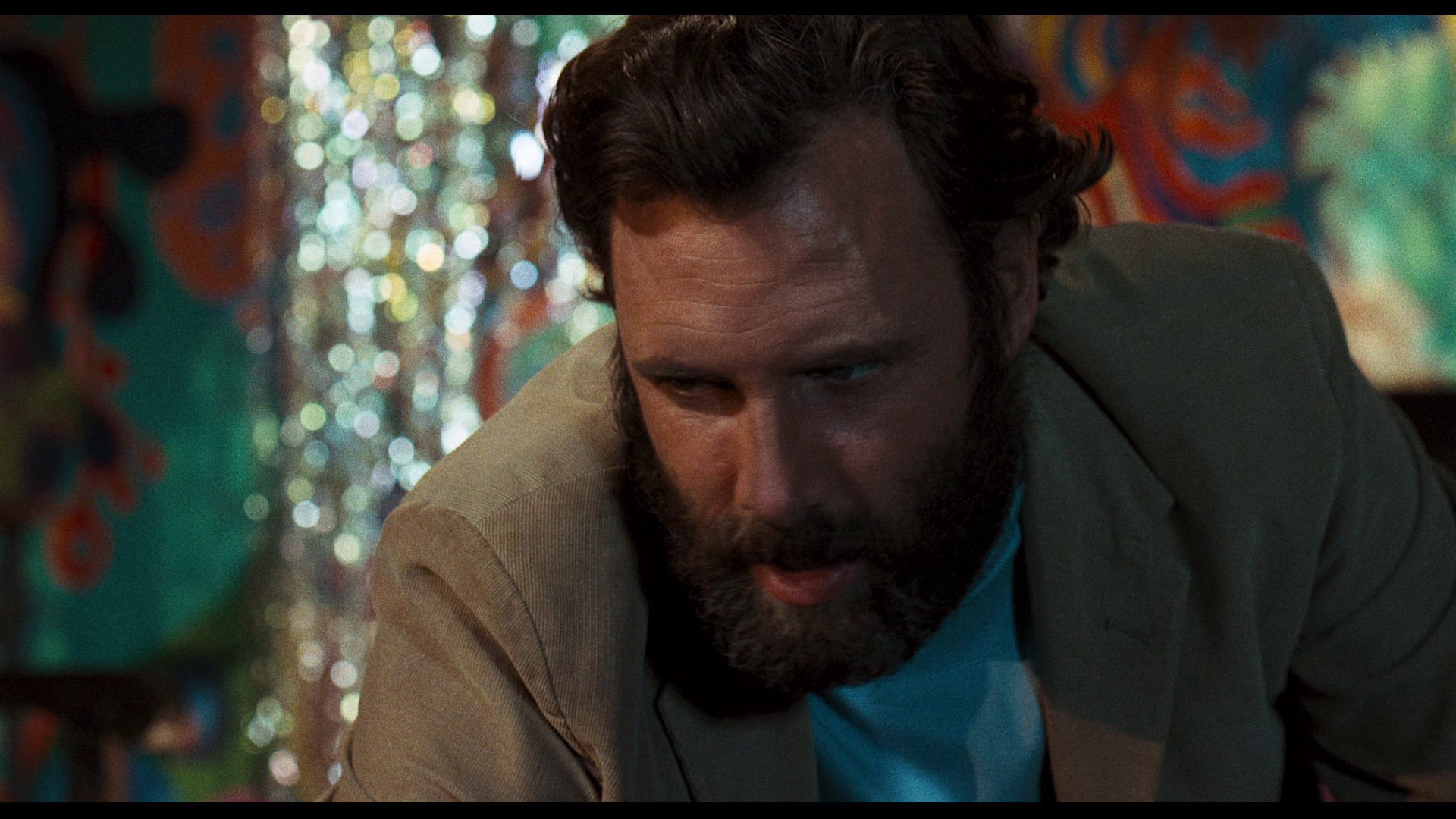

Video

Taking up around 19Gb of space on its disc, this presentation of The Trip is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The excellent colour reproduction, a huge improvement over the film’s previous home video releases, is evident from the outset and supports the film’s use of bold primary colours very well. Contrast levels are very nicely-balanced, assisting the picture’s transition from the brightly-lit desert scenes to the low-light photography of the Gothic fantasy sequence. Throughout the film, a very good level of detail is present within the image, with facial close-ups exhibiting this aspect of the presentation most overtly. Finally, a superb encode ensures that the film retains the structure of 35mm film, resulting in a very organic, natural appearance to the picture. Taking up around 19Gb of space on its disc, this presentation of The Trip is in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. The excellent colour reproduction, a huge improvement over the film’s previous home video releases, is evident from the outset and supports the film’s use of bold primary colours very well. Contrast levels are very nicely-balanced, assisting the picture’s transition from the brightly-lit desert scenes to the low-light photography of the Gothic fantasy sequence. Throughout the film, a very good level of detail is present within the image, with facial close-ups exhibiting this aspect of the presentation most overtly. Finally, a superb encode ensures that the film retains the structure of 35mm film, resulting in a very organic, natural appearance to the picture.

NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track, with accompanying optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. This track is clear with good range (the dialogue is sometimes a little quiet in the mix, but this would seem to be a feature of the original sound mix itself), and the subtitles are accurate and easy to read.

Extras

The disc contains an array of contextual material: - an audio commentary with Roger Corman. This commentary track previously appeared on the film’s previous DVD release from MGM. Corman talks about his preparation for the film and the process of shooting it. He discusses his relationship with AIP too. It’s a good track, informative and interesting. - a featurette, ‘Tune In, Trip Out’ (17:16). Again, this has been carried over from the film’s previous MGM DVD release. It features input from Corman, Dern and Allen Daviau (who designed the film’s psychedelic effects). Dern asserts that he was ‘not into the drug culture at all. Because I ran everyday, I thought drugs would make me grow hair on my palm or go crazy or something’. Dern says that ‘The [drug] culture bothered me’, and ‘it bothered me even more’ because he was playing a character immersed in that drug culture – ‘and not because I disdained it or put it down. If they wanted to do that, fine: I drank Coca Cola all day, I was just as stoned as they were, only I didn’t know it. I was a caffeine freak, I mean the first think I ask for today is a Coke and a donut; who am I kidding?’ Corman talks about the context of the film’s production. He says that independent filmmakers understood ‘the beat of young people more’ than the major studios. Both The Wild Angels and The Trip were a deliberate break away from the period settings and studiobound nature of Corman’s Poe pictures. The contributors talk about Nicholson’s script for the film; Corman says that the only problem with the script was the Nicholson ‘wrote some effects in that we couldn’t do with our budget’. Corman also talks about his preparation for the film, including reading Timothy Leary’s book, and Corman’s own experiment with LSD. - the prologue (0:45) and alternate ending (3:21) imposed by AIP. Both include an optional commentary from Roger Corman. (This commentary seems to have been ‘snipped’ from the feature’s audio commentary on the MGM DVD release, the main presentation of which incorporated AIP’s prologue and ending.) In his comments over AIP’s prologue, Corman says that the prologue was added without his knowledge and ‘I disagree totally with everything that’s said on the screen’. In his comments over the ending, Corman discusses his intention with the film’s resolution was to show that Paul had both good and bad experiences during his ‘trip’, whereas ‘AIP wanted to say “This is a bad trip, and LSD is no good”. I don’t think anything was gained with that crack [on the screen]. I don’t think anybody understands it anyway’. - Interview with Allen Daviau (8:00). Here, Daviau talks about the film’s psychedelic film effects, which he designed. He talks about shooting these effects, particularly in the sequence in which the psychedelic lights are projected onto the bodies of Fonda, Strasberg and Sachse, on 50ASA film that was pushed two stops. - Psychedelic Light Box (5:45). This is a montage of the psychedelic light effects used within the film. - Poster and Stills Gallery (0:17). - Trailer (2:27).

Overall

Rather than a film about drugs, The Trip feels much more like a picture about a man’s anxieties surrounding his divorce and his ambiguous relationships with women. (This is perhaps a product of Nicholson’s own feelings when writing the screenplay for the film.) The picture begins with an image of an idealised relationship: the man and woman in Paul’s commercial, kissing contentedly before turning towards the camera; dressed like bride and groom, they are literally walking on water. The constructed nature of this scenario is foregrounded when the woman turns towards the camera and addresses the audience directly, and the camera pans away to reveal Paul and his cameraman, the film’s audience being made aware that this is a scenario concocted by Paul for the television commercial he is shooting. This fantasy is soon juxtaposed with the reality of Paul’s own marriage, his wife Sally visiting the shooting location to remind Paul that he has missed the appointment for his divorce. Although much of the picture focuses on Paul’s LSD-induced hallucinations, the film’s narrative returns time and time again to Paul’s divorce (represented either directly or symbolically within his ‘trip’) and his relationships with Sally and Glenn; Paul’s final revelation seems to be as much about his relationships with women as his experience with LSD. In some ways, the LSD and the trip it induces could be seen as a ‘Maguffin’. Rather than a film about drugs, The Trip feels much more like a picture about a man’s anxieties surrounding his divorce and his ambiguous relationships with women. (This is perhaps a product of Nicholson’s own feelings when writing the screenplay for the film.) The picture begins with an image of an idealised relationship: the man and woman in Paul’s commercial, kissing contentedly before turning towards the camera; dressed like bride and groom, they are literally walking on water. The constructed nature of this scenario is foregrounded when the woman turns towards the camera and addresses the audience directly, and the camera pans away to reveal Paul and his cameraman, the film’s audience being made aware that this is a scenario concocted by Paul for the television commercial he is shooting. This fantasy is soon juxtaposed with the reality of Paul’s own marriage, his wife Sally visiting the shooting location to remind Paul that he has missed the appointment for his divorce. Although much of the picture focuses on Paul’s LSD-induced hallucinations, the film’s narrative returns time and time again to Paul’s divorce (represented either directly or symbolically within his ‘trip’) and his relationships with Sally and Glenn; Paul’s final revelation seems to be as much about his relationships with women as his experience with LSD. In some ways, the LSD and the trip it induces could be seen as a ‘Maguffin’.

The Trip is a film that – in some superficial ways – may seem slightly ‘dated’ (especially in its depiction of drugs culture, as suggested by the BBFC examiners’ changing accounts of it), but which is in many other ways a fascinating one. Signal One’s new Blu-ray release contains a very pleasing presentation of the film and some wonderful contextual material. Perhaps most importantly, the film itself, as presented on this disc, removes the two most harmful amendments made by AIP (the prologue and the changes to the closing scene). It’s an excellent release and comes with a strong recommendation. References BBFC, 2015: ‘Case Studies: The Trip’. [Online.] http://www.bbfc.co.uk/case-studies/trip Dern, Bruce, 2007: Things I’ve Said But Probably Shouldn’t: An Unrepentant Memoir. London: John Wiley & Sons Grant, Barry Keith, 2008: American Cinema of the 1980s: Themes and Variations. Rutgers University Press Eliot, Marc, 2013: Nicholson: A Biography. New York: Crown Archetype Love, Damien, 2009: ‘Nearer My Corman to Thee: Roger Corman, Bruce Dern and David Carradine’. In: Morris, Gary (ed), 2009: Action!: Interviews with Directors from Classical Hollywood to Contemporary Iran. London: Anthem Press: 153-72 Parker, John, 2007: Jack: The Biography of Jack Nicholson. John Blake Publishing Schupp, Patrick, 1973: ‘Meeting with Roger Corman’. In: Nasr, Constantine (ed), 2011: Roger Corman: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi: 83-9 Siff, Stephen, 2015: Acid Hype: American News Media and the Psychedelic Experience. University of Illinois Press Winkler, Peter L, 2012: Dennis Hopper: The Wild Ride of a Hollywood Rebel. Biteback Publishing

|

|||||

|