|

|

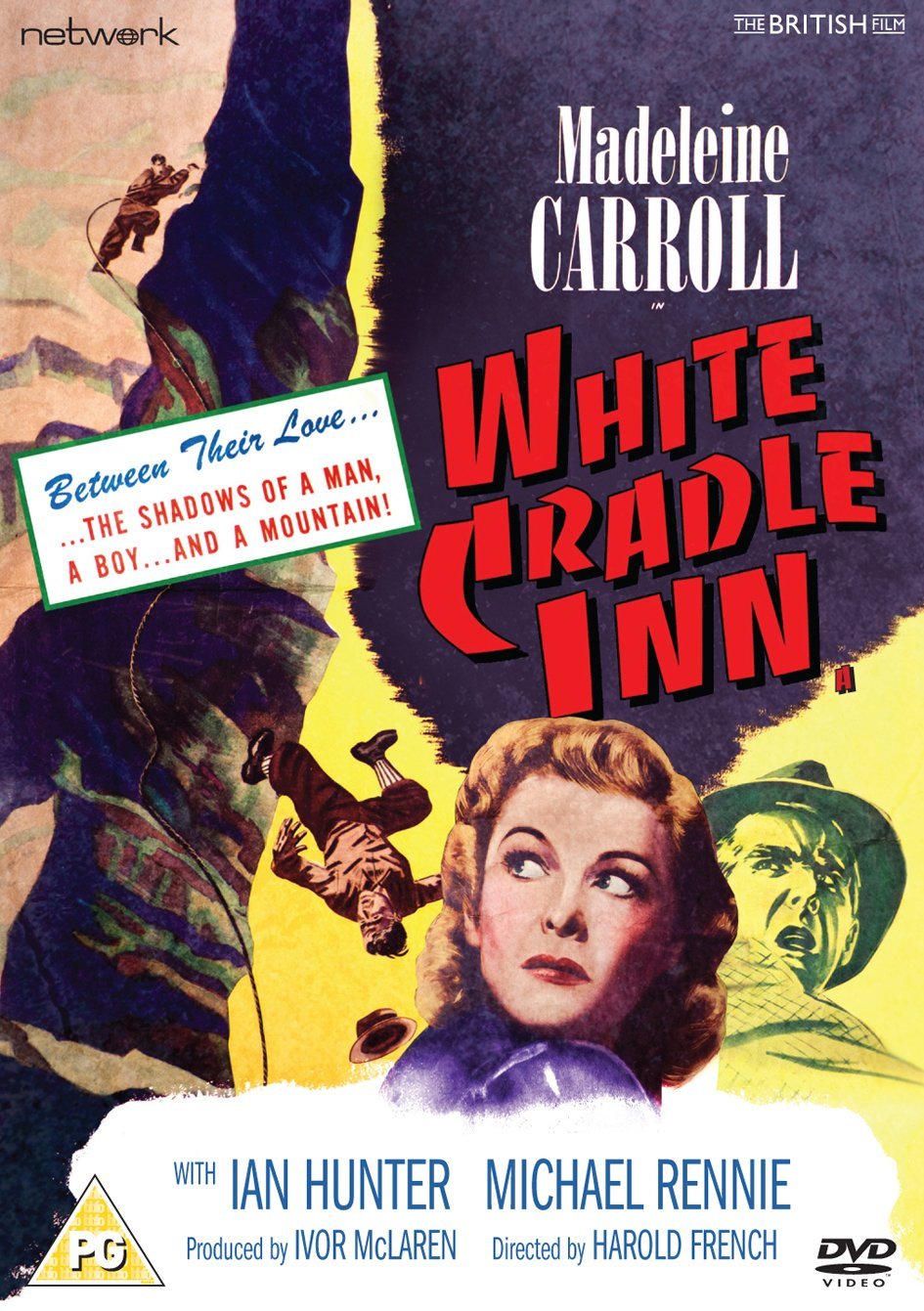

White Cradle Inn AKA High Fury

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (7th June 2015). |

|

The Film

White Cradle Inn AKA High Fury (Harold French, 1947) White Cradle Inn AKA High Fury (Harold French, 1947)

Described simply in a 1949 issue of The Rotarian (following its US release in 1948) as a ‘simple story, warm hearted, real’, Harold French’s White Cradle Inn (1947) tells a very straightforward but profoundly touching story (Lockhart, 1949: 34). The film is also notable as one of the final films of Madeleine Carroll, one of the very few pictures in which she acted after the war, with the film’s narrative somewhat echoing Carroll’s work during the Second World War as a Red Cross nurse and her donation of her Parisian chateau to the care of over a hundred and fifty orphans. White Cradle Inn also reunited Madeleine Carroll with Michael Rennie, who had taken an uncredited role, his acting debut, in Hitchcock’s Secret Agent (1936) – in which Carroll, of course, starred. Taking place just after the Second World War, the film focuses on a small Swiss town where a number of French children, evacuees from the war, have been living. Young Roget (Michael McKeag), one of these evacuees, lives with the caring Magda (Carroll) and her lazy, jealous husband Rudolph (Rennie). Magda owns the titular inn which provides for the family, an arrangement which Rudolph sees as a slight against his masculinity. Rudolph is also a known womaniser who is conducting an affair with Louisa (Anne-Marie Blanc), convinced that he can ‘pull the wool over her [his wife Magda’s] eyes’. Roget is an orphan and witnessed his parents killed before his eyes by the SS. Rudolph is unsympathetic to this, and sees Roget’s presence as yet another challenge to his relationship with Magda. Soon, it is ordered that the French evacuees, including Roget, must be returned to France. Roget, who will end up in an orphanage, refuses to leave. A farewell celebration is held in the town for the evacuees. ‘If there is another war, we’ll be straight back’, one of the children jokes. However, as the train is pulling away from the station Roget escapes from it and hides.  Roget returns to Magda, who hides him in one of the rooms within the inn. Magda also enlists the help of the town’s doctor, Anton (Ian Hunter). However, Rudolph becomes aware of Roget’s presence, and when Magda asks for Rudolph’s permission to adopt Roget officially (thus ensuring he can stay with Magda in Switzerland), Rudolph sees this as an opportunity to arrange a deal: he will sign the necessary paperwork in return for Magda signing over the inn, which has been in her family for five generations, to him. Roget returns to Magda, who hides him in one of the rooms within the inn. Magda also enlists the help of the town’s doctor, Anton (Ian Hunter). However, Rudolph becomes aware of Roget’s presence, and when Magda asks for Rudolph’s permission to adopt Roget officially (thus ensuring he can stay with Magda in Switzerland), Rudolph sees this as an opportunity to arrange a deal: he will sign the necessary paperwork in return for Magda signing over the inn, which has been in her family for five generations, to him.

The film opens with beautiful shots of the Swiss countryside. Soon, we see Roget on his bicycle, running errands for Magda and Rudolph. Back at the inn, Rudolph complains that Roget is half an hour late, suggesting that Roget will have ‘some cock and bull story about a blue butterfly or a pink caterpillar’. ‘He uses his eyes’, the maid Maria (Margarete Hoff) tells Rudolph, ‘He notices what the good God made’, and suggests that Rudolph only uses his eyes for ogling the attractive young women of the town. Maria chastises Rudolph for turning out Roget’s night light. ‘It gets on my nerves, a boy like that wanting a light every night’, an unsympathetic Rudolph complains. Roget, Anton suggests, has suffered a form of what in modern parlance would be labeled as PTSD, following the murder of his parents: ‘When you came here, my dear boy, you were a wounded soldier’, Anton tells Roget, ‘But the wounds were in your mind. Now they’re almost healed’. However, Rudolph is entirely disinterested in Roget’s wellbeing. ‘Why are you always so unkind to him?’, Louisa asks Rudolph. ‘I don’t like him’, is Rudolph’s simple reply. Later, Rudolph complains that Roget’s fear of the dark makes him a coward: ‘I’ve already told you I’ve had enough of that kid’, Rudolph tells Magda when she asks if Roget can stay with them, ‘I’ve no use for cowards, that’s all’. ‘He ought to be told he’s got to behave like other people. He always does something different’, Rudolph grumbles shortly after Roget has, unbeknownst to Rudolph, escaped from the train that is to return him to France. ‘He is different’, Magda reminds her husband, ‘His life’s been different’.  Aside from Rudolph, who Anton diagnoses as suffering from both ‘the peasant’s desire to earn his four walls and his lands’ and ‘the natural male desire to be the breadwinner and the boss’, the film saves a special displeasure for the bureaucrats who order the return of the evacuees, regardless of the specific circumstances surrounding each evacuees relationship with their host family. Scenes depicting the bureaucrats see their words undercut by carnival-type music. When the order is given for the evacuees to return to France, Magda suggests that Roget must be allowed to stay and pooh-poohs the orders of ‘a miserable government official in Berne who thinks only of figures’. Aside from Rudolph, who Anton diagnoses as suffering from both ‘the peasant’s desire to earn his four walls and his lands’ and ‘the natural male desire to be the breadwinner and the boss’, the film saves a special displeasure for the bureaucrats who order the return of the evacuees, regardless of the specific circumstances surrounding each evacuees relationship with their host family. Scenes depicting the bureaucrats see their words undercut by carnival-type music. When the order is given for the evacuees to return to France, Magda suggests that Roget must be allowed to stay and pooh-poohs the orders of ‘a miserable government official in Berne who thinks only of figures’.

The film also punctures idealistic myths about childhood and the nostalgia that many feel towards it. During the farewell celebration that is held for the evacuees as they board the train back to France, two women from the town discuss the departure of the children with Anton. ‘Oh, the happiness of childhood’, one of the women says, ‘I’d give anything in the world to be a child again, wouldn’t you, doctor?’ ‘Madame, I could think of nothing I’d dislike more’, Anton responds matter-of-factly. When released in America, in 1948 under the title High Fury, White Cradle Inn was cut to 71 minutes. This DVD contains the full-length British version of the film, running 80:44 mins (PAL).

Video

White Cradle Inn is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The monochrome photography is served well be a clean, clear source print which evidences good contrast: the midtones are strong, though the blacks are quite heavily ‘crushed’ in a few sequences. There is some minor damage here and there (white flecks and specks, indicating debris on the negative) but otherwise, the film is in remarkably good shape.

NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track. Dialogue is mostly clear but there is a slight wavering of pitch during the opening music and some slightly distracting flutter that interferes with some of the dialogue later in the film. Sadly, no subtitles are included.

Extras

There is no contextual material on this disc.

Overall

For many years a difficult film to see, White Cradle Inn is a touching, sincere film. Rennie is suitably chauvinistic and unsympathetic as Rudolph, though the film’s final moments make an attempt to redeem the character; and Carroll offers a caring performance as Magda that echoes with the actress’ real-life activities during the Second World War. For many years a difficult film to see, White Cradle Inn is a touching, sincere film. Rennie is suitably chauvinistic and unsympathetic as Rudolph, though the film’s final moments make an attempt to redeem the character; and Carroll offers a caring performance as Magda that echoes with the actress’ real-life activities during the Second World War.

This disc contains a good presentation of the film, though the audio track contains some flutter that obscures a few lines of dialogue. Nevertheless, it’s a pleasing release that, although sadly bereft of any contextual material, should make a worthwhile purchase for fans of British cinema – especially given the relative rarity of the film on home video formats. References: Lockhart, Jane, 1949: ‘Looking at Movies’. The Rotarian (May 1949): 34-5 Spicer, Andrew, 2003: Typical Men: The Representation of Masculinity in Popular British Cinema. London: I B Tauris

This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|