|

|

Visitor (The) AKA Stridulum (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (19th October 2014). |

|

The Film

The Visitor (Giulio Paradisi, 1979)  Giulio Paradisi’s The Visitor (released in Italy as Stridulum) was based on a story by Ovidio Assonitis, whose later work includes writing and producing the very American ecological actioner Choke Canyon (Charles Bail, 1986), and was scripted by Lou Comici – whose later credits as a writer include work on the American television series Due South (1994-9) and Walker: Texas Ranger (1993-2001). The film is both curiously Italian and strangely American – especially in its use of recognisable American actors of bygone eras, in a cast that is comparable to that of Michael Winner’s roughly contemporaneous The Sentinel (1977). Winner’s film features American actors associated with Classical Hollywood (including Ava Gardner, Martin Balsam, John Carradine, Jose Ferrer, Arthur Kennedy, Eli Wallach and Burgess Meredith) ‘slumming it’ in a highly-derivative horror picture, alongside some rising stars (Chris Sarandon, Jeff Goldblum, Christopher Walken); similarly, The Visitor features John Huston, Mel Ferrer, Shelley Winters, Sam Peckinpah and Glenn Ford in acting roles, alongside Lance Henriksen, who would of course go on to become one of the most recognisable American character actors of the 1980s (and beyond). Giulio Paradisi’s The Visitor (released in Italy as Stridulum) was based on a story by Ovidio Assonitis, whose later work includes writing and producing the very American ecological actioner Choke Canyon (Charles Bail, 1986), and was scripted by Lou Comici – whose later credits as a writer include work on the American television series Due South (1994-9) and Walker: Texas Ranger (1993-2001). The film is both curiously Italian and strangely American – especially in its use of recognisable American actors of bygone eras, in a cast that is comparable to that of Michael Winner’s roughly contemporaneous The Sentinel (1977). Winner’s film features American actors associated with Classical Hollywood (including Ava Gardner, Martin Balsam, John Carradine, Jose Ferrer, Arthur Kennedy, Eli Wallach and Burgess Meredith) ‘slumming it’ in a highly-derivative horror picture, alongside some rising stars (Chris Sarandon, Jeff Goldblum, Christopher Walken); similarly, The Visitor features John Huston, Mel Ferrer, Shelley Winters, Sam Peckinpah and Glenn Ford in acting roles, alongside Lance Henriksen, who would of course go on to become one of the most recognisable American character actors of the 1980s (and beyond).

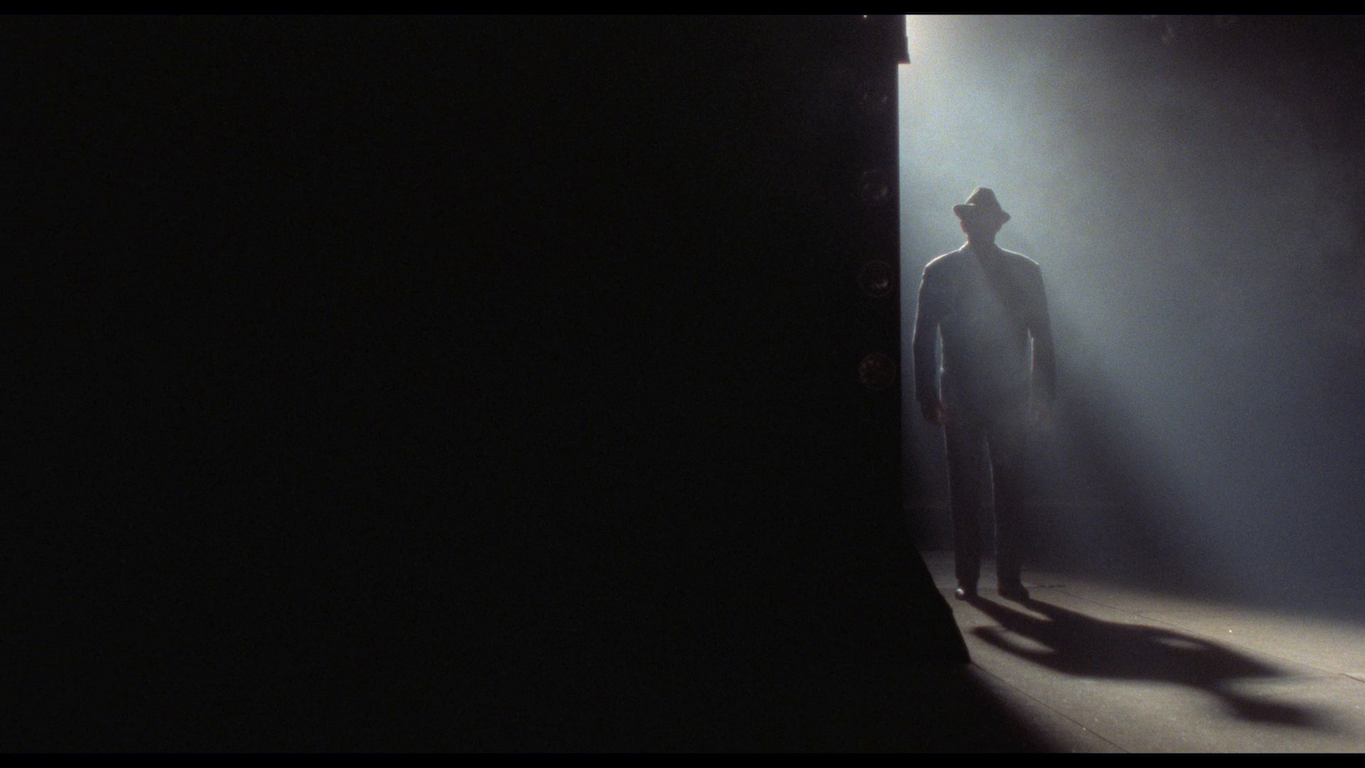

Italian riffs on The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) aren’t exactly rare: that particular filone was tapped numerous times, in films such as Il medaglione insanguinato (The Cursed Medallion/The Night Child; Massimo Dallamano, 1975), L’Anticristo (The Antichrist/The Tempter; Alberto De Martino, 1974), Un urlo dalle tenebre (Cries and Shadows/Naked Exorcism/The Return of the Exorcist; Franco Lo Cascio & Angelo Pannaccio, 1975) and Malabimba (Andrea Bianchi, 1979). These films predominantly feature a young woman or child who is possessed by an evil spirit (in Il medaglione insanguinato, this possession is linked to the ownership of a ‘cursed’ medallion; in Malabimba, the possession is a result of a séance that has ‘gone wrong’). The Visitor has a similar sense of focus, highlighting the extent to which many of these films about sweet-seeming little girls who are revealed to be working for the forces of darkness look backwards to Mervyn LeRoy’s The Bad Seed (1956), an adaptation of William March’s 1954 novel of the same title, in which the mother of eight year old Rhoda Penmark (Patty McCormack) gradually comes to the realisation that her daughter is a sociopath (her sociopathy is suggested to be genetic, the mother discovering that she herself is the biological daughter of a convicted serial killer) who is guilty of committing the murder of one of her peers. In The Visitor, Barbara Collins (Joanne Nail) is gradually forced into the realisation that her eight year old daughter Katie (Paige Conner) is, like the unknowing Barbara, the descendant of an intergalactic evil entity named Zatin.  The film begins on an alien planet, with the depiction of a conflict between Yarveth (John Huston) and Zatin, described in the narration which accompanies this sequence – revealed to be a tale told by an uncredited Franco Nero to a group of bald-headed children – as an ancient evil who escaped imprisonment and fled to Earth. Zatin, we are told, was ‘a mutant with a primal wish to kill, but evolved to new psychic and occult powers. He used these powers to spread destruction and death’. An army of birds was trained to hunt and kill Zatin, who transformed himself into an eagle so as to combat those who were hunting him. Zatin was killed by the birds, but before this, he ‘mated with Earth women, procreating numerous children, thereby transmitting his wicked spirit and evil powers through new generations. Yet the struggle continues and still goes on’. These descendants of Zatin were pursued by the descendents of Yarveth. The film begins on an alien planet, with the depiction of a conflict between Yarveth (John Huston) and Zatin, described in the narration which accompanies this sequence – revealed to be a tale told by an uncredited Franco Nero to a group of bald-headed children – as an ancient evil who escaped imprisonment and fled to Earth. Zatin, we are told, was ‘a mutant with a primal wish to kill, but evolved to new psychic and occult powers. He used these powers to spread destruction and death’. An army of birds was trained to hunt and kill Zatin, who transformed himself into an eagle so as to combat those who were hunting him. Zatin was killed by the birds, but before this, he ‘mated with Earth women, procreating numerous children, thereby transmitting his wicked spirit and evil powers through new generations. Yet the struggle continues and still goes on’. These descendants of Zatin were pursued by the descendents of Yarveth.

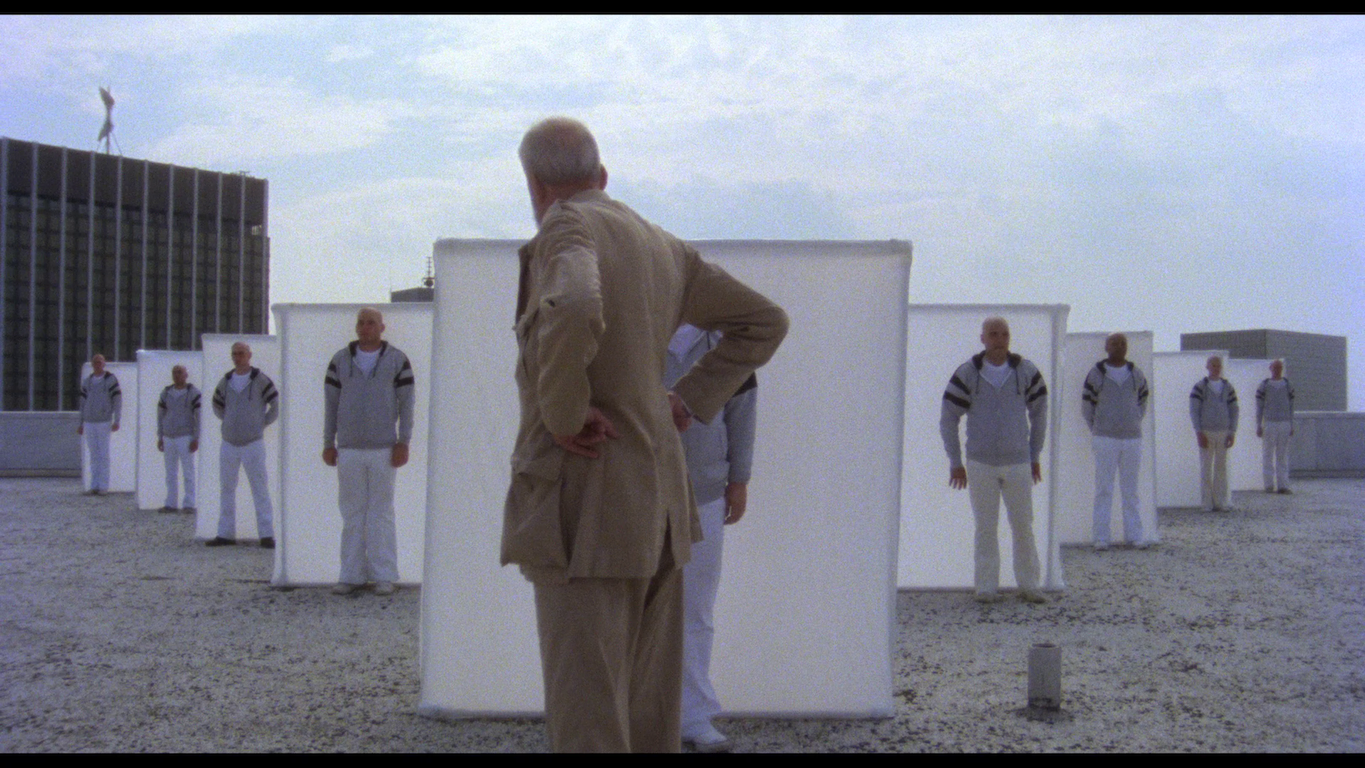

Only one child descendant of Zatin remains: Katie Collins, daughter of Barbara. Barbara is involved with Raymond (Lance Henriksen), the new owner of a basketball team in Atlanta, Georgia. Katie’s supernatural powers are demonstrated for the first time when, during a basketball game featuring Ray’s team, she makes the basketball explode moments before the opposing team score a last-minute goal. Ray’s ownership of the team is financed by his association with a mysterious cabal, led by Dr Walker (Mel Ferrer). Walker and his group have enlisted Ray to impregnate Barbara, so that she may give birth to another descendant of Zatin. However, Barbara is reluctant to marry Ray, thus frustrating Walker’s plan. Barbara admits that Katie sometimes ‘scares me’, after Katie threatens that, one of these days, I’m really gonna klll her [her babysitter]’. At Katie’s eighth birthday party, she is given as a gift a box containing a loaded pistol; the gun accidentally discharges, shooting Barbara in the spine. Barbara is paralysed from the waist down by the injury and must remain in a wheelchair (‘Mother didn’t die, but she just won’t won’t be able to walk anymore’, Katie tells her gymnastics instructor nonchalantly). Barbara is forced to hire a housekeeper, Jane Phillips (Shelley Winters), to take care of her home. Phillips, it seems, has encountered one of Katie’s/Zatin’s kind before, and is fully aware of the child’s deadly potential.  Meanwhile, a descendant of Yarveth, who goes by the Earth name of Jerzy (also played by John Huston), arrives in Atlanta seeking Katie. Barbara refuses to submit to Ray’s demands that she marry him, and Walker’s committee go to more desperate measures to impregnate Barbara, including abducting her from her car and taking her aboard a spaceship disguised as a lorry, where she is subjected to artificial insemination. However, when she discovers that she is pregnant, she turns to her ex-husband (Sam Peckinpah), a doctor working in a non-profit clinic (in contrast with the expensive medicine practiced by Walker and his cronies), and asks him to help arrange an abortion for her. All of this takes place as Jerzy, assisted by a number of bald clones from his homeworld, closes in on Katie, who is protected by a falcon which defends her from any would-be attackers. Meanwhile, a descendant of Yarveth, who goes by the Earth name of Jerzy (also played by John Huston), arrives in Atlanta seeking Katie. Barbara refuses to submit to Ray’s demands that she marry him, and Walker’s committee go to more desperate measures to impregnate Barbara, including abducting her from her car and taking her aboard a spaceship disguised as a lorry, where she is subjected to artificial insemination. However, when she discovers that she is pregnant, she turns to her ex-husband (Sam Peckinpah), a doctor working in a non-profit clinic (in contrast with the expensive medicine practiced by Walker and his cronies), and asks him to help arrange an abortion for her. All of this takes place as Jerzy, assisted by a number of bald clones from his homeworld, closes in on Katie, who is protected by a falcon which defends her from any would-be attackers.

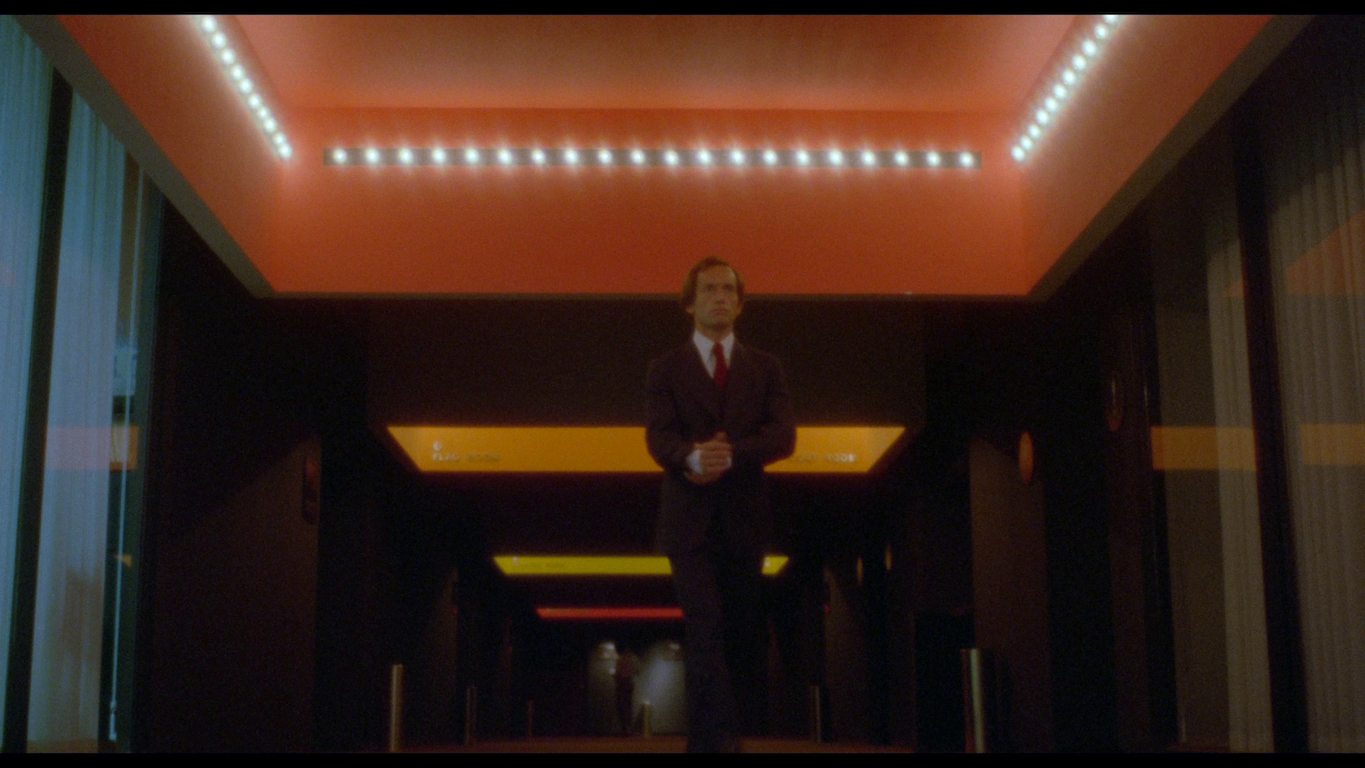

Barbara seems implicitly aware of her predicament, telling Ray (the first time he asks her to marry him), ‘I’m not a normal person [….] There’s something wrong inside, something terrible’. Katie, meanwhile, seems entirely cognisant of her heritage and Dr Walker’s conspiracy against her mother – and Ray’s involvement in this conspiracy. Jane Phillips has, we are led to believe, had a previous encounter with one of Katie’s kind and immediately sees the child for what she is. Phillips tells Barbara that Katie is ‘bad’. ‘What do you mean, “bad”’?’, Barbara asks, ‘She’s just a little girl’. To this, Phillips responds enigmatically: ‘You be careful [that] you ward of the influences of Saturn. You’ve suffered enough, understand’. Later, Phillips slaps Katie, telling her, ‘For once in your life, you will be polite’, before asserting angrily, ‘The moment I walked into this house I recognised you for what you were. You little monster. You see, unfortunately, I had one of my own. I know how to treat them. So you be careful. You watch out, or you’ll be sorry’.  Like many of the other ‘bad seed’ films (and other more loosely-related films dealing with monstrous offspring, such as David Cronenberg’s The Brood, 1979; Larry Cohen’s It’s Alive, 1974; and Gabrielle Beaumont’s The Godsend, 1980), The Visitor locates horror within the nuclear family. The conspirators are depicted as shadowy corporate types who seduce the ‘father’ within this unit (Ray) via promises of unlimited wealth. It’s a patriarchal conspiracy, perpetuated by men of a certain age, that has the aim of using Ray to impregnate Barbara, producing a male child, a brother to Katie. The all-male Illuminati-style cabal, chaired by Dr Walker, offers a nod towards the conspiracy thrillers of the era: the shots depicting the meetings of this cabal recall the sequences focusing on the meetings of the Star Chamber in Peter Hyams’ The Star Chamber (1983), for example. Like many of the other ‘bad seed’ films (and other more loosely-related films dealing with monstrous offspring, such as David Cronenberg’s The Brood, 1979; Larry Cohen’s It’s Alive, 1974; and Gabrielle Beaumont’s The Godsend, 1980), The Visitor locates horror within the nuclear family. The conspirators are depicted as shadowy corporate types who seduce the ‘father’ within this unit (Ray) via promises of unlimited wealth. It’s a patriarchal conspiracy, perpetuated by men of a certain age, that has the aim of using Ray to impregnate Barbara, producing a male child, a brother to Katie. The all-male Illuminati-style cabal, chaired by Dr Walker, offers a nod towards the conspiracy thrillers of the era: the shots depicting the meetings of this cabal recall the sequences focusing on the meetings of the Star Chamber in Peter Hyams’ The Star Chamber (1983), for example.

There is something genocidinal in the attempts that have been made by Yarveth’s kind to wipe out the descendants of Zatin, who is framed in the opening narration as a ‘primal’ evil – despite the attempts made in the closing sequence to suggest that Yarveth’s descendants have simply stripped these children of the ‘evil’ that possesses them, assimilating them into the crop of bald children that sit at the feet of Franco Nero’s character as he tells them of the past conflicts between Zatin and Yarveth’s descendants. Katie’s transition from evil ‘bad seed’ to good child is partially represented through her physical transformation: her long, well-maintained hair, previously kept in pigtails (an image foregrounded on Arrow’s newly-commissioned cover art for this release), is stripped from her. The way this transformation from ‘bad’ to ‘good’ is symbolised through this physical transformation makes a subtle association of ‘evil’ with girl’s/women’s vanity (often symbolised through women’s hair and the attention paid towards it, in terms of styling it or dressing it up), reinforcing the patriarchal connotations of Yarveth’s quest – not to mention Dr Walker’s insidious attempts to get Raymond to impregnate Barbara and her womb that, in Dr Walker’s words, ‘transcends the world of everyday reality’. (At the end of the film, Ray, the male ‘head’ of the family, attempts to garrote Barbara whilst declaring that she ‘ruined everything. You refused intervention’ – the intervention, presumably, of patriarchy and its strictures, which Barbara resists by refusing to marry Ray.)  Assonitis would revisit the ‘bad seed’ paradigm a number of times during his career, including his final film as a writer, Red Riding Hood (Giacomo Cimini, 2003), which focuses on a twelve year old girl (Susanna Satta) who, after being abandoned by her mother, takes on the role of a vigilante, aided in her attempts to clean the streets of Rome of ‘undesirables’ by George (Simone Dipascasio), a biker who wears a wolf mask. Assonitis’ career was dominated by a slavish devotion to the filone, from the The Exorcist-inspired Chi sei? (Beyond the Door; Assonitis, 1974), to Tentacoli (Tentacles; Assonitis, 1977), clearly modeled on the success of Spielberg’s Jaws (1975). The Visitor draws on a wide variety of models: its focus on a child possessed of supernatural powers seems clearly inspired by films like The Omen (Richard Donner, 1976) and The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973), whilst the scenes of birds attacking characters allude overtly to Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). The opening narration (‘Once, far away, light years, distances beyond thought, a great slender ship with a trail of fire slid through the father reaches of space. On that ship was Zatin… a prisoner named Zatin. Words cannot describe his evil, his criminality’) suggests the influence of Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977), whilst the images that open the film (a bowed Yarveth encountering Zatin, who slowly wanders towards Yarveth with a red sun burning behind her/him) suggests both Omar Sharif’s entrance in Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1963) and the face-off between the demon Pazuzu and Father Merrin (Max Von Sydow) in the opening sequence of The Exorcist. Some of the visual effects refer to the iconography of Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and in its climax The Visitor also contains an oddball allusion to the hall of mirrors sequence in Orson Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai (1946). Assonitis would revisit the ‘bad seed’ paradigm a number of times during his career, including his final film as a writer, Red Riding Hood (Giacomo Cimini, 2003), which focuses on a twelve year old girl (Susanna Satta) who, after being abandoned by her mother, takes on the role of a vigilante, aided in her attempts to clean the streets of Rome of ‘undesirables’ by George (Simone Dipascasio), a biker who wears a wolf mask. Assonitis’ career was dominated by a slavish devotion to the filone, from the The Exorcist-inspired Chi sei? (Beyond the Door; Assonitis, 1974), to Tentacoli (Tentacles; Assonitis, 1977), clearly modeled on the success of Spielberg’s Jaws (1975). The Visitor draws on a wide variety of models: its focus on a child possessed of supernatural powers seems clearly inspired by films like The Omen (Richard Donner, 1976) and The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973), whilst the scenes of birds attacking characters allude overtly to Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). The opening narration (‘Once, far away, light years, distances beyond thought, a great slender ship with a trail of fire slid through the father reaches of space. On that ship was Zatin… a prisoner named Zatin. Words cannot describe his evil, his criminality’) suggests the influence of Star Wars (George Lucas, 1977), whilst the images that open the film (a bowed Yarveth encountering Zatin, who slowly wanders towards Yarveth with a red sun burning behind her/him) suggests both Omar Sharif’s entrance in Lawrence of Arabia (David Lean, 1963) and the face-off between the demon Pazuzu and Father Merrin (Max Von Sydow) in the opening sequence of The Exorcist. Some of the visual effects refer to the iconography of Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and in its climax The Visitor also contains an oddball allusion to the hall of mirrors sequence in Orson Welles’ The Lady From Shanghai (1946).

In America, on its original release, The Visitor was distributed in an abbreviated version which omitted approximately 20 minutes of footage (and on which director Giulio Paradisi was credited as ‘Michael J Paradise’). These cuts made the already obtuse narrative even less coherent. (In the American version, for example, the fact that Sam Peckinpah’s character is Barbara’s ex-husband is never made clear.) This is the longer European version of the film, running 108:46 minutes. NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Video

The film was shot in colour, on 35mm stock. This presentation is based on the restoration by Drafthouse Films, which Drafthouse released on Blu-ray in the US earlier this year (2014). The presentation, using the AVC codec, takes up over 20Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, and is in the 1.85:1 aspect ratio (which seems to be the intended aspect ratio).  The film is in very good shape, but there is some minor damage present here and there. Contrast and colour reproduction are impressive, as is the level of detail within the image (within the confines of the original photography, of course, and the fact that Drafthouse’s restoration seems to be based on a print rather than the negative), and the film has an organic grain structure, as befitting 35mm film stock from the late-1970s. Some sequences were shot using diffused light and/or diffusion filters on the lenses, so those sequences have a soft, diffuse aesthetic that is true to the original photography.

Audio

Audio is presented by a LPCM 2.0 mono track, in English, that is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. This audio track is clear and audible throughout. During some sequences, there is some analogue hiss in the background, but this never overwhelms the audio track.

Extras

The disc includes interviews with The disc includes interviews with

- actor Lance Henriksen (9:01). In this fascinating and entertaining interview, Henriksen discusses the shooting of the film and his initial reaction to it, upon seeing it in a cinema in Times Square. - screenwriter Lou Comici (9:09). Comici talks about his role as the film’s writer, hired by Assonitis owing to Comici’s ability to speak and comprehend English. Ultimately, Comici suggests, he was the victim of the conflict between Assonitis and Paradisi, and was fired after his draft of the film was completed. - cinematographer Ennio Guarnieri (4:25). Guarnieri is interviewed in Italian, with English subtitles. He discusses the techniques involved in the production of the film. Theatrical Trailer (1:47). This is a newly-constructed trailer, put together for the Drafthouse rerelease. An ‘easter egg’ is also included. On the ‘extras’ menu, highlight the interview with Lance Henriksen and press right on your remote to highlight the bird icon. Press ‘Enter’ to see a short clip (0:42) of Henriksen talking about safety on the set during the scene depicting the birds attacking Barbara’s house at the climax of the film.

Overall

The narrative shoots off on all sorts of tangents, which is perhaps the source of accusations that the film’s plotting is incoherent. (The film does have a clear narrative, of sorts, but its focus on communicating this narrative is sometimes lost.) For example, a subplot involving Glenn Ford as a detective who takes it upon himself to investigate the shooting of Barbara, resulting in his death, goes nowhere and offers little to the main narrative – other than a great scene in which Ford arrives at Katie’s school and, rather creepily (an aspect emphasised by the anxiety Ford embodies in his performance), asks Katie, ‘Isn’t there something you’d like to say to me that you’ve never said before?’ ‘Yeah’, Katie responds: ‘Go fuck yourself’. The narrative shoots off on all sorts of tangents, which is perhaps the source of accusations that the film’s plotting is incoherent. (The film does have a clear narrative, of sorts, but its focus on communicating this narrative is sometimes lost.) For example, a subplot involving Glenn Ford as a detective who takes it upon himself to investigate the shooting of Barbara, resulting in his death, goes nowhere and offers little to the main narrative – other than a great scene in which Ford arrives at Katie’s school and, rather creepily (an aspect emphasised by the anxiety Ford embodies in his performance), asks Katie, ‘Isn’t there something you’d like to say to me that you’ve never said before?’ ‘Yeah’, Katie responds: ‘Go fuck yourself’.

There are some fantastic sequences which take place in huge, modernist structures dominated by harsh angles and shadows – suggesting a focus on the type of alienation facilitated by the modern world that is highlighted in David Cronenberg films such as Shivers (1975), via its depiction of Starliner Towers, and Scanners (1981), through the offices of BioCarbon Amalgamate. In one of these sequences, Katie causes havoc at an ice-skating rink situated within a huge shopping mall, intercut with ominous shots of Jerzy descending a staircase, the camera situated at the bottom of the stairs, looking up, and the frame dominated by chiaroscuro shapes. (A similar use of an ice rink located within a shopping mall as a site of havoc occurs in Johnny Mak’s Hong Kong crime picture The Long Arm of the Law, 1984.) Elsewhere, the dialogue strives to be portentous but more frequently provokes unintentional laughter. When Jerzy arrives at Atlanta airport, a customs officer asks him, ‘What is the purpose of your trip?’, to which Jerzy responds: ‘I’m a visitor’. Later, Walker tells Ray that, ‘Power corrupts, Raymond, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. But we must have that power’. In what is arguably the film’s most oddball sequence, Jerzy arrives at Barbara’s home and tells her that he is the new babysitter. ‘Babysitter?’, Barbara queries, looking at the elderly man with suspicion. ‘People are often surprised’, Jerzy tells her benignly. ‘Excuse my surprise’, Barbara responds, ‘we usually get teenage girls’. ‘I’m definitely not that’, Jerzy tells her. Shortly after, we see Barbara and Ray driving away from the house, having left Jerzy in charge of Katie. ‘You don’t think he’s [Jerzy] a child molester?’, Ray asks, with hardly a hint of concern in his voice. Barbara, at this point in the film wheelchair-bound, pooh-poohs this suggestion, saying that the agency vet their babysitters very carefully, before adding, ‘What about you, aren’t you a cripple molester?’ ‘Well’, Ray responds, ‘I would be if you gave me half a chance’. Ultimately, The Visitor is a bizarre but never less than entertaining film. The presentation on this Blu-ray is very good indeed, and there’s some strong contextual material (although the now out of print DVD release from Code Red in the US features two exclusive audio commentaries and a featurette). Fans of off-kilter cinema will find much to enjoy here.

|

|||||

|