|

|

Ring of Spies AKA Ring of Treason AKA Shadow of Treason

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (25th July 2014). |

|

The Film

Ring of Spies AKA Ring of Traitors AKA Shadow of Treason (Robert Tronson, 1964)  Written by Frank Launder, Ring of Spies was based on the Portland affair of 1961, one of a series of security scandals that shook Harold Macmillan’s government during the early 1960s; the worst of these would, of course, be the Profumo scandal that took place in 1963. In 1961, five people were arrested for passing information from the Admiralty Underwater Weapons Establishment, in Portland, on to the KGB. The spy ring was broken up after a CIA mole within the KGB (Polish military intelligence officer Michael Goleniewski, codenamed ‘Sniper’) revealed in 1959 that information about the Royal Navy’s new undersea warfare equipment (including Britain’s first nuclear submarine, the HMS Dreadnought) was being passed on to Soviet agents. The five people arrested for their involvement in this act of espionage were two clerks at the Portland base, Harry Houghton and Ethel Gee; a Ruislip-based bookseller named Peter Kroger and his wife Helen; and a Canadian named Gordon Lonsdale who acted as a conduit, passing information from Houghton and Gee to the Krogers. The Krogers would reduce the data to microdots, which would then be hidden in antique books that the Krogers would smuggle out of Britain and into Russia. Written by Frank Launder, Ring of Spies was based on the Portland affair of 1961, one of a series of security scandals that shook Harold Macmillan’s government during the early 1960s; the worst of these would, of course, be the Profumo scandal that took place in 1963. In 1961, five people were arrested for passing information from the Admiralty Underwater Weapons Establishment, in Portland, on to the KGB. The spy ring was broken up after a CIA mole within the KGB (Polish military intelligence officer Michael Goleniewski, codenamed ‘Sniper’) revealed in 1959 that information about the Royal Navy’s new undersea warfare equipment (including Britain’s first nuclear submarine, the HMS Dreadnought) was being passed on to Soviet agents. The five people arrested for their involvement in this act of espionage were two clerks at the Portland base, Harry Houghton and Ethel Gee; a Ruislip-based bookseller named Peter Kroger and his wife Helen; and a Canadian named Gordon Lonsdale who acted as a conduit, passing information from Houghton and Gee to the Krogers. The Krogers would reduce the data to microdots, which would then be hidden in antique books that the Krogers would smuggle out of Britain and into Russia.

During the trial (which Launder attended prior to writing this film), Ethel Gee claimed that she was unaware that the information she was stealing from the base was being passed on to Soviet agents. Gee asserted that she believed Lonsdale to be Alex Johnson, an American naval commander and an ally who was simply interested in investigating what Britain was doing with information that had been passed on to it by the US. Gee did not believe that she had involved in anything criminal. Meanwhile, Houghton, who had previously had connections within the black market during his time working as a naval attaché at the British Embassy in Warsaw, claimed that he had been cajoled into co-operating with Lonsdale and the Krogers in response to threats against his life and the lives of Gee and Houghton’s ex-wife. Lonsdale, meanwhile, was a mystery: he was known to be a Canadian businessman who rented jukeboxes and gambling machines to pubs in London, but his history could only be traced back to 1954, and it was widely believed that he was a Russian agent living under a stolen identity.  Houghton and Gee were sentenced to fifteen years in prison but were released in 1970. They married shortly after. Meanwhile, Lonsdale (or the man known as Lonsdale) was given a twenty-five year sentence; however, in 1964, not long after the release of Ring of Spies, Lonsdale was traded with the Soviets for Greville Wynne, the British MI6 agent who had been captured in Russia in 1963. Peter and Helen Kroger, eventually revealed to be two known spies named Morris and Lona Cohen, were given twenty years in prison but were traded in 1969 for a British citizen held by the Soviets, Gerald Brooke. Houghton and Gee were sentenced to fifteen years in prison but were released in 1970. They married shortly after. Meanwhile, Lonsdale (or the man known as Lonsdale) was given a twenty-five year sentence; however, in 1964, not long after the release of Ring of Spies, Lonsdale was traded with the Soviets for Greville Wynne, the British MI6 agent who had been captured in Russia in 1963. Peter and Helen Kroger, eventually revealed to be two known spies named Morris and Lona Cohen, were given twenty years in prison but were traded in 1969 for a British citizen held by the Soviets, Gerald Brooke.

This film dramatisation of these events casts Bernard Lee as Harry Houghton, and begins with Houghton’s days as a naval attaché in Warsaw. In these early scenes, Houghton is depicted as an alcoholic and something of a lech. Early in the film, during a party at the British Embassy in Warsaw, Houghton propositions a waitress and causes a scene; in response, he is told to report to his commanding officer’s office ‘at 0900 tomorrow’. That night, he is visited by a local prostitute named Christina, who later will pass his information on to the KGB; when he returns to the UK, Houghton is initially brought in to the spy ring after he is blackmailed about his relationship with Christine in Warsaw. At the meeting with his superior, Houghton is warned that he is ‘a bad security risk’ and is to be sent home; but shortly after, he is shown back home in the UK, bring driven to the Underwater Weapons Division in Portland, an officer telling him ‘They reckon this is the most hush-hush joint in the country’. The reasons for the posting of Houghton, the ‘bad security risk’, in Portland, ‘the most hush-hush joint in the country, is ambiguous within the film: we are uncertain as to whether he is posted there simply due to administrative incompetence (were the details of his escapades in Warsaw minimised or simply overlooked?), or has been deliberately placed there by a double-agent working higher up within the department. Much later in the film, we are shown more senior figures within British intelligence who are also working for the KGB, so the latter explanation is within the realms of extreme possibility. Thankfully, the filmmakers refuse to spoonfeed us; the ambiguity surrounding this scenario reinforces the sense that Houghton (and his associate Gee) is simply a pawn in a much larger game.  These early scenes highlight Houghton’s resentment at the position he has been given. Lying on his bed, drunk after the party and slurring his words, he tells Christina of his ambitions, frustrated by the fact that he does not come from the right social class, and his belief that money is the cure for all ills: ‘In the Navy since I was fifteen. Could have worked my way up [….] Haven’t been to the right school, “not the officer type, old boy” [….] [I]f you haven’t got it, money’ll buy it. Money’ll buy anything’. Later, in Portland, he will meet Elizabeth ‘Bunty’ Gee (Margaret Tyzak). Realising she has access to the safe where the information he needs to pass on to Lonsdale is kept, Houghton begins a relationship with her; initially, for Houghton it is a relationship of convenience, but eventually the two appear to fall in love. Houghton recognises Bunty, who is 38, to be a spinster with little experience of the world (‘She’s led a sheltered life’, he tells Lonsdale at one point), and he seduces her by taking her to parties and nightclubs. He explains to her his relativistic philosophy, which she also shares to some degree: ‘Always take an inch or two off the regulations’, he tells her during a night out, ‘whatever they may be. In our job, we’re surrounded by regulations. I mean, intelligent people like ourselves, we use our common sense. Those that are worth keeping, we keep. Those that aren’t worth keeping, we ignore’. Houghton taps into Bunty’s own sense of resentment about her low pay, so as to bring her into his scheme: ‘How do you feel about money?’, he asks her, ’Do you ever think about it? [….] I don’t know what you’re getting, but I bet together we earn less than the chap who sweeps up the factory floor [….] And you know why? Because we’re suckers’. Part of what Houghton and Gee do is motivated by a desire to be recognised. ‘Do you remember what you said in the Black Bull a few weeks back, about little people who think themselves important?’, Bunty asks Houghton at one point, ‘Well, we’re little people, and we are important, aren’t we?’ Houghton and Gee desire a better life for themselves (Houghton lives in a caravan and wishes to buy a house; Bunty exclaims that she would like to own a car), and so their betrayal is to some extent motivated by greed, but also there is a suggestion that people working within such fields should be paid more handsomely, thus removing the temptation to sell information to enemy agents. Of course, towards the end of the film it is the fact that Houghton and Bunty spend beyond their means that draws attention to them and leads to their capture. The police even go as far as adding up how much Houghton spends in the pub. These early scenes highlight Houghton’s resentment at the position he has been given. Lying on his bed, drunk after the party and slurring his words, he tells Christina of his ambitions, frustrated by the fact that he does not come from the right social class, and his belief that money is the cure for all ills: ‘In the Navy since I was fifteen. Could have worked my way up [….] Haven’t been to the right school, “not the officer type, old boy” [….] [I]f you haven’t got it, money’ll buy it. Money’ll buy anything’. Later, in Portland, he will meet Elizabeth ‘Bunty’ Gee (Margaret Tyzak). Realising she has access to the safe where the information he needs to pass on to Lonsdale is kept, Houghton begins a relationship with her; initially, for Houghton it is a relationship of convenience, but eventually the two appear to fall in love. Houghton recognises Bunty, who is 38, to be a spinster with little experience of the world (‘She’s led a sheltered life’, he tells Lonsdale at one point), and he seduces her by taking her to parties and nightclubs. He explains to her his relativistic philosophy, which she also shares to some degree: ‘Always take an inch or two off the regulations’, he tells her during a night out, ‘whatever they may be. In our job, we’re surrounded by regulations. I mean, intelligent people like ourselves, we use our common sense. Those that are worth keeping, we keep. Those that aren’t worth keeping, we ignore’. Houghton taps into Bunty’s own sense of resentment about her low pay, so as to bring her into his scheme: ‘How do you feel about money?’, he asks her, ’Do you ever think about it? [….] I don’t know what you’re getting, but I bet together we earn less than the chap who sweeps up the factory floor [….] And you know why? Because we’re suckers’. Part of what Houghton and Gee do is motivated by a desire to be recognised. ‘Do you remember what you said in the Black Bull a few weeks back, about little people who think themselves important?’, Bunty asks Houghton at one point, ‘Well, we’re little people, and we are important, aren’t we?’ Houghton and Gee desire a better life for themselves (Houghton lives in a caravan and wishes to buy a house; Bunty exclaims that she would like to own a car), and so their betrayal is to some extent motivated by greed, but also there is a suggestion that people working within such fields should be paid more handsomely, thus removing the temptation to sell information to enemy agents. Of course, towards the end of the film it is the fact that Houghton and Bunty spend beyond their means that draws attention to them and leads to their capture. The police even go as far as adding up how much Houghton spends in the pub.

There is a subtle escalation in the compromises that Houghton and Bunty are forced to make by Lonsdale (William Sylvester) and the Krogers (David Kossoff and Nancy Nevinson). When Houghton is first approached by an enemy agent (not Lonsdale) who threatens to blackmail Houghton over his relationship with the prostitute Christina in Warsaw, Houghton refuses, asserting ‘You’re barking up the wrong tree [….] When I left Warsaw, I started a clean page’. However, he eventually gives in to the pressure exerted on him. ‘Suppose I did get you a few tidbits now and then…’, Houghton suggests, and the enemy agent persuades him to do so by telling him that such information is practically ‘a matter of public record these days’. There is a subtle escalation in the compromises that Houghton and Bunty are forced to make by Lonsdale (William Sylvester) and the Krogers (David Kossoff and Nancy Nevinson). When Houghton is first approached by an enemy agent (not Lonsdale) who threatens to blackmail Houghton over his relationship with the prostitute Christina in Warsaw, Houghton refuses, asserting ‘You’re barking up the wrong tree [….] When I left Warsaw, I started a clean page’. However, he eventually gives in to the pressure exerted on him. ‘Suppose I did get you a few tidbits now and then…’, Houghton suggests, and the enemy agent persuades him to do so by telling him that such information is practically ‘a matter of public record these days’.

Although it’s evident that their crimes are serious acts of treason, the film has some sympathy for Harry and Bunty, depicting them as pawns within a much larger game. As Tony Shaw notes, ‘[u]nlike similar films ten years earlier […] the pair are not condemned outright’ (2006: 59). Instead, Shaw argues, Ring of Spies ‘makes an attempt to focus on the psychology of contemporary treason’, focusing on the ‘sad and tragic lives’ that are led by Harry and Bunty, ‘partly related to the mind-numbing nature of their work’ (ibid.). They seek excitement and, badly paid (or so they argue), desire to be recognised and rewarded for their work. Houghton is a blowhard, ‘but he is endowed with enough charm and warmth to make us understand his weaknesses’ (ibid.). Shaw quotes the contemporary review from Films and Filming, in which the writer noted that ‘The film almost persuades us that, in their shoes, we could have acted as they did’ (quoted in ibid.). Harry and Bunty only do what they do because they live in ‘an increasingly materialistic and valueless society’ that encourages their fascination with material goods and their love of leisure, which allows Lonsdale to seduce them into acting as spies with parties and promises of money (ibid.). Lonsdale, Shaw argues, ‘is merely feeding the pleasure-seeking desires’ that have been instilled in Harry and Bunty by the society in which they live (ibid.). However, Harry and Bunty are doomed to be undervalued: as they are underpaid in their day jobs, Harry and Bunty are also short-changed by the KGB, never receiving the payments they are promised – this is one of the ways in which the KGB string them along. ‘Must there be a next time, Harry?’, Bunty asks at one point. ‘You saw how much the cheque was for’, Houghton responds, ‘Won’t even buy me a house’.  Ring of Spies takes a semi-documentary approach, comparable to American semi-documentary films noirs such as Elia Kazan’s Boomerang! (1947) and, more pertinently, the spy drama House on 92nd Street (Henry Hathaway, 1945) – which focused on a Nazi spy ring within the US. There’s a low-key approach to the material, with a lack of non-diegetic music; and, as with many semi-documentary noirs, there’s a detailed focus on procedural elements – from the techniques used by the spies themselves (we are shown, cinema of process-like, the methods by which the Krogers reduce the data Lonsdale gives them to microdots) and by the agents investigating the spy ring. Like many of the semi-documentary films noirs (such as House on 92nd Street), Ring of Spies opens and closes with a narrator who offers a context for the film’s narrative, identifying names, places, dates and facts about the events that are depicted within the film. Given the low-key nature of the majority of the film, the opening and closing narrations within Ring of Spies are surprisingly sensationalistic. The opening sequence contains a montage of newsreel footage and short scenes depicting various activities related to espionage, whilst a narrator reflects on the long history of espionage, the romantic depictions of spycraft in fiction, and the ways in which espionage has adopted new technologies: ‘Ever since men distrusted one another […] there have been spies, prying eyes taking note of enemy dispositions, hastening back with vital information. Until some time in the last century, they took on a certain glamour and became romantic figures in melodramas or featured in the glorious absurdities of the early cinema [….] The times have changed, and so have the methods. Today, spying has turned almost into a minor industry, a cold reality of the Cold War, helped by every modern device’. The narrator ends by telling us that the story we are about to watch ‘is in all its basic essentials the true story of one such group of people’. Meanwhile, the closing narration reinforces the paranoia at the heart of the story: ‘But there are still more [spies] in our midst, looking and acting like ordinary citizens. Who knows? There may be a spy in this very theatre, perhaps in the row in which you are sitting, another link in the same unending chain. As one cell is closed, another opens, and so the dark business of espionage goes on’. Ring of Spies takes a semi-documentary approach, comparable to American semi-documentary films noirs such as Elia Kazan’s Boomerang! (1947) and, more pertinently, the spy drama House on 92nd Street (Henry Hathaway, 1945) – which focused on a Nazi spy ring within the US. There’s a low-key approach to the material, with a lack of non-diegetic music; and, as with many semi-documentary noirs, there’s a detailed focus on procedural elements – from the techniques used by the spies themselves (we are shown, cinema of process-like, the methods by which the Krogers reduce the data Lonsdale gives them to microdots) and by the agents investigating the spy ring. Like many of the semi-documentary films noirs (such as House on 92nd Street), Ring of Spies opens and closes with a narrator who offers a context for the film’s narrative, identifying names, places, dates and facts about the events that are depicted within the film. Given the low-key nature of the majority of the film, the opening and closing narrations within Ring of Spies are surprisingly sensationalistic. The opening sequence contains a montage of newsreel footage and short scenes depicting various activities related to espionage, whilst a narrator reflects on the long history of espionage, the romantic depictions of spycraft in fiction, and the ways in which espionage has adopted new technologies: ‘Ever since men distrusted one another […] there have been spies, prying eyes taking note of enemy dispositions, hastening back with vital information. Until some time in the last century, they took on a certain glamour and became romantic figures in melodramas or featured in the glorious absurdities of the early cinema [….] The times have changed, and so have the methods. Today, spying has turned almost into a minor industry, a cold reality of the Cold War, helped by every modern device’. The narrator ends by telling us that the story we are about to watch ‘is in all its basic essentials the true story of one such group of people’. Meanwhile, the closing narration reinforces the paranoia at the heart of the story: ‘But there are still more [spies] in our midst, looking and acting like ordinary citizens. Who knows? There may be a spy in this very theatre, perhaps in the row in which you are sitting, another link in the same unending chain. As one cell is closed, another opens, and so the dark business of espionage goes on’.

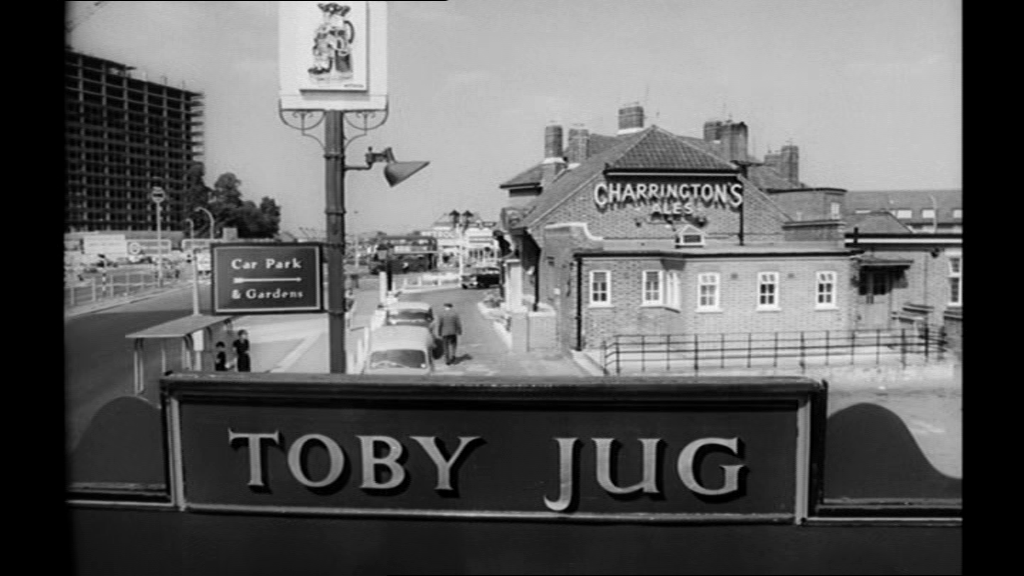

As R Barton Palmer has asserted, the semi-documentary films noirs explored and highlighted ‘the dark underside of American culture and institutions […] and the guilty, antisocial desires usually buried deep within the human heart’ (2013: np). Ring of Spies has a similar agenda. One of the things that’s interesting about the film’s depiction of spycraft is the utter normalcy that surrounds it. We are shown Lonsdale in his work as a jukebox salesman; exchanges take place in pubs and cafes; late in the film, we are shown more double agents working within British intelligence, these ones different from Houghton and Bunty only because they are less naïve and more senior within the establishment, able to cover their tracks; microdots are produced in the Kroger’s unremarkable suburban home in Ruislip. The use of popular entertainment venues as a cover for espionage is subversive. Where music hall entertainment was often used as a signifier of solidarity, offering ‘a communal venue in which the traditional mixing of classes […] engenders a sense of national community’, Harry and Bunty’s trip to see the Crazy Gang during a visit to London is used ironically (Geraghty, 2002: 15). The sense of national identity and community symbolised by the show they are watching is juxtaposed with (and undercut by) the knowledge of their treachery: the sequence in which they visit the theatre is cross-cut with a scene depicting Lonsdale, Peter and Helen turning the data Harry and Bunty have passed to them into microdots which are to be passed on to the KGB. The Krogers’ suburban home is utterly normal and equally unremarkable. When Lonsdale arrives at the Kroger house with the data passed on to him by Bunty and Gee, Helen Kroger closes the curtains. Lonsdale asks, ‘What if the neighbours get suspicious of those drawn curtains?’ In response, Peter Kroger tells him, ‘The English are great lovers of privacy and eccentricity. A man who buys and sells old books, and bolts and bars his house at night? This is a man that’s worth of respect, not suspicion’. The film is uncut and runs for 86:44 mins (PAL).

Video

The film is presented in 1.66:1, which would seem to be its intended aspect ratio (at least, judging by the compositions). The presentation is anamorphically enhanced. The monochrome photography is represented nicely here, with good contrast and tonality. There is some wear and tear evident throughout (noticeable vertical lines here and there, for example), but nothing too distracting.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track, which is clean and clear throughout. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

The disc includes the films original trailer (2:44) and a stills gallery (1:00). The original pressbook is also included, as a .PDF file.

Overall

Ring of Spies is a fascinating espionage drama, closely rooted in the true events of the Portland case. What’s interesting about this film, especially in the era of the early James Bond films (in which, of course, Bernard Lee would become typecast as M, the head of MI5), is its depiction of the utter normalcy of the contexts in which acts of espionage are shown as taking place. Houghton and Bunty, despite their treachery, are sympathetic characters, driven by the frustrations in their lives which are exploited by the enemy agents. When the investigation into the spies kicks in, we are shown the daily grind of surveillance: detectives spend uneventful days surveilling the suspects, gathering information; they gather fingerprints of used milk bottles; they watch Houghton in the pub, counting how much he spends. Ring of Spies is a fascinating espionage drama, closely rooted in the true events of the Portland case. What’s interesting about this film, especially in the era of the early James Bond films (in which, of course, Bernard Lee would become typecast as M, the head of MI5), is its depiction of the utter normalcy of the contexts in which acts of espionage are shown as taking place. Houghton and Bunty, despite their treachery, are sympathetic characters, driven by the frustrations in their lives which are exploited by the enemy agents. When the investigation into the spies kicks in, we are shown the daily grind of surveillance: detectives spend uneventful days surveilling the suspects, gathering information; they gather fingerprints of used milk bottles; they watch Houghton in the pub, counting how much he spends.

The film isn’t dour, however. There are some amusing moments. Notable amongst these is a sequence in which detectives follow Houghton and Bunty as they drive along country roads. Two policewomen are disguised as nuns driving a car. Houghton and Bunty pass the care containing the two disguised police officers. ‘Did you see who we just passed?’, Bunty asks, laughing. Tronson cuts to the car containing the policewomen, clad in the garb of nuns, one of them declaring, ‘Don’t let the bastards get too far ahead, Doris, or you’ll have someone come between us’. Elsewhere, when two detectives take a room in a lodging house opposite the home of Lonsdale, they encounter a landlady who tells them that her late husband wouldn’t let enquiry agents take out a room in the building because he was a Catholic and didn’t believe in divorce. Ultimately, Ring of Spies is an excellent, thought-provoking film. This DVD release contains a very good presentation of the film itself, but it would have been nice to see a little more contextual material. Nevertheless, fans of espionage dramas, or even fans of films noirs (with which this film shares much in common), will find this a worthwhile purchase. References: Geraghty, Christine, 2002: British Cinema in the Fifties: Gender, Genre and the New Look. London: Routledge Palmer, R Barton, 2013: ‘Borderings: The Film Noir Semi-Documentary’. In: Spicer, Andrew & Hanson, Helen (eds), 2013: A Companion to Film Noir. London: Blackwell Shaw, Tony, 2006: British Cinema and the Cold War: The State, Propaganda and Consensus. London: I B Tauris This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|